Myths and Facts: Obesity

What are the true causes of the obesity epidemic that now affects more than one-third of people globally? And, do the measures thought to prevent obesity really work?

- By Ronale Tucker Rhodes, MS

OBESITY WAS ONCE considered to be simply a major public health threat. But, in 2013, the American Medical Association (AMA) at its annual meeting voted to declare obesity a chronic disease. That vote came only after impassioned debate, with many unconvinced that it met the criteria for disease. Russell Kridel, MD, then-incoming-chair of the AMA Council on Science and Public Health, was one of the dissenters: “It’s more like smoking. Smoking isn’t a disease. Smoking can cause disease such as lung cancer and emphysema in the same way that obesity can lead to diabetes and hypertension. We’re really talking nomenclature here, not philosophy.” Nevertheless, Dr. Kridel did agree that “there is no debate about the importance and urgency of addressing the problem.”1

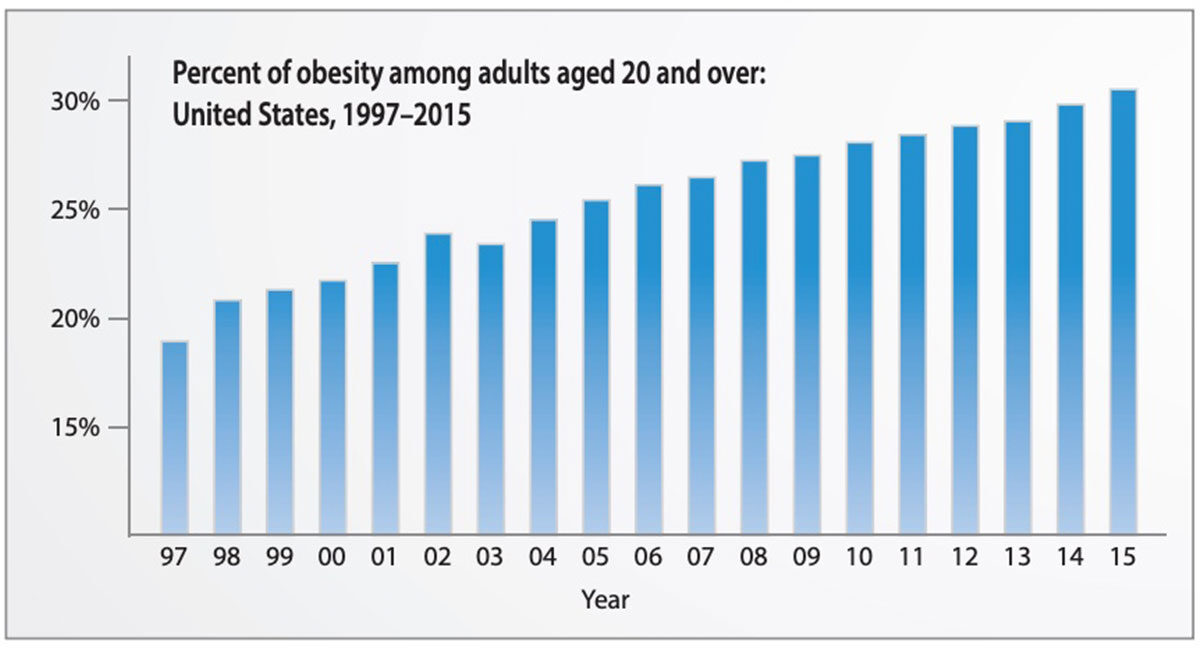

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 2011 and 2014, more than one-third (36.5 percent) of U.S. adults were obese, and more than 17 percent of youth were obese.2 And CDC predicts these rates will rise. It estimates that 42 percent of Americans will be obese by 2030.3 Just what factors contribute to the cause of obesity and how to reverse it are not well understood. In fact, a pervasive number of myths and presumptions about obesity need clarification — not just for those who suffer from it, but also for those who treat it.

Separating Myth from Fact

Myth: The obesity epidemic is exaggerated.

Fact: There has been criticism over the years that the number of overweight and obese individuals is overstated. The reason: It relies on body mass index (BMI) scores. But, despite arguments that BMI classifications don’t account for varying factors, most organizations agree and some studies show that BMI is a reasonable indicator and the best option.

In 1998, the National Institutes of Health lowered the overweight threshold for BMI to match international guidelines, as well as to “help primary care providers address weight management as a pathway to promoting the health of their patients.”4,5 The move added 30 million Americans who were previously in the “healthy weight” category to the “overweight” category, more than doubling the size of the category.4 According to the book An Epidemic of Obesity Myths published in 2005, this meant that actors Tom Cruise, Sylvester Stallone and Mel Gibson, as well as baseball players Sammy Sosa and Barry Bonds and boxer Mike Tyson, were technically obese.6

CDC acknowledges there are clinical limitations of BMI that need to be considered. For instance, “factors such as age, sex, ethnicity and muscle mass influence the relationship between BMI and body fat. And, BMI doesn’t distinguish between excess fat, muscle or bone mass, nor does it provide any indication of the distribution of fat among individuals.”7 Because muscle weighs more than fat, individuals who are muscular can fall into the overweight status, even if their fat levels are low. And, “BMI doesn’t tease apart different types of fat, each of which can have different metabolic effects on health. BMI cannot take into consideration, for example, where the body holds fat” such as in the belly or under the skin (visceral fat), according to an article in the journal Science. The problem with this is that relatively thin people who are considered healthy by BMI standards can have high levels of visceral fat, putting them at higher risk of developing health problems related to weight gain.8

Yet, while there are better ways to measure body fat, they are also a lot more expensive, eliminating them as an everyday option. And, while it has been suggested that doctors rely not just on BMI but also hormones and biomarkers in the blood or urine to better understand the processes that may contribute to obesity and chronic disease, until such tests become available, BMI is still the most useful indicator of overweight and obesity.8

Moreover, the growing prevalence of obesity is clear due to an abundance of observational and experimental data, both among adults and children.9 Worldwide, the rate of obesity has nearly doubled since 1980, with just over 200 million adult men and just under 300 million adult women obese, accounting for 39 percent of all adults.10 “With the continuing rise in obesity and limited treatment efficacy, options for averting a poor public health outcome seem to rest either on the hope that scientists are wrong in their projections or speedy investment in the development of more effective public health measures to deal with it,” say Robert W. Jeffrey, PhD, professor of epidemiology and community health at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, and Nancy E. Sherwood, PhD, a research investigator for HealthPartners Research Foundation. “We think the second option [is] a more prudent scientific and policy choice.”9

Myth: Obesity is genetic.

Fact: Obesity is rarely caused by genes; however, some people may be genetically predisposed to obesity. According to the Harvard School of Public Health, researchers have identified certain rare instances in which obesity seems to be caused solely by genetic mutations.11 To date, studies have identified more than 30 candidate genes on 12 chromosomes associated with BMI.12 But even people who carry genes associated with obesity don’t become overweight, and vice versa, because weight is also influenced by lifestyle factors.11

In 2013, two studies found mutations in genes that could explain weight gain, but the mutations account for only less than 5 percent of obesity in society. In a mouse study conducted at Boston Children’s Hospital, researchers found that mutations in the Mrap2 gene led the animals to eat less initially but still gain about twice as much weight as they normally would. When their appetites returned, the mice continued to gain weight even though they were fed the same number of calories as a group of control mice. They determined the mice were simply sequestering fat rather than breaking it down for energy. Like people, mice contain two copies of the Mrap2 gene. Mice with just one defective copy experienced significant weight gain, but not as much as mice with two defective copies.12

The second study conducted at the University College London divided a group of 359 healthy men of normal weight by the FTO gene status, the majority of whom had low-risk versions of the gene, while 45 had mutations linked to greater appetite and caloric consumption. To determine how the altered genes were affecting appetite, the researchers measured levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin before and after meals. Those with the mutated FTO gene did not show the same drop in ghrelin levels to signify they were full as did the men with the low-risk FTO gene.12

Myth: A person can be obese and healthy.

Fact: Despite reports to the contrary, studies show that a person cannot be obese and healthy. In one study conducted at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in 2013, researchers found that overweight and obesity were associated with 18.2 percent of all deaths among adults from 1986 through 2006 in the U.S. Previous estimates established the obesity-related death rate at only approximately 5 percent. In addition, the study showed that the more recent the birth year, the greater effect obesity has on mortality rates. And, contrary to claims made in public health literature, obesity is not protective in the elderly.13

A second study in 2014 of more than 14,000 men and women aged 30 to 59 years found that those who were obese had more plaque buildup in their arteries, putting them at greater risk for heart disease and stroke than people of normal weight. In the study, researchers at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Center in Seoul, Korea, scanned the hearts of 14,828 people who had no apparent risk factors for heart disease to look for buildup of calcium plaque in the heart arteries. They found that obese people had a higher prevalence of atherosclerosis of the heart arteries than people of normal weight, which if not managed, can lead to heart attack and sudden cardiac death, among other heart conditions. “There has long been debate about the relative importance to health of fitness versus fatness. The argument has been made that if one is fit, fatness may not be a significant health concern,” said David Katz, MD, MPH, FACPM, FACP, FACLM, director of the Yale University Prevention Research Center. “Excess body fat can increase inflammation, one of the key factors contributing to heart disease, and other chronic diseases as well.”14

And yet another study conducted in 2016 found that overweight and obesity are associated with higher all-cause mortality and mortality related to coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, respiratory disease and cancer. In the study, researchers from the Global BMI Mortality Collaboration investigated the association between BMI and mortality in 3,951,455 people from 189 studies in multiple countries. Analysis was limited to individuals who were never-smokers, did not have preexisting chronic disease and who survived the first five years of follow-up. Of these, 385,879 died during the study period. There was a nonlinear association between BMI and mortality for each major cause of death in each major region included in the study, with BMI greater than 25 showing a strong positive correlation with CHD, stroke and respiratory disease mortality, and a moderate positive correlation with cancer mortality.15

Myth: A calorie in is/is not a calorie out.

Fact: Whether a calorie is a calorie when it comes to weight loss has been a considerable source of debate. According to the “calories in, calories out” mindset, obesity is simply a matter of eating too many calories. A pound of fat is 3,500 calories, so if a person eats 500 calories less than they burn every day, after a week, a pound of fat will have been lost. But, it does appear that while calories do matter, not all calories are equal. It’s just not very well understood.

A calorie is a measure of energy. According to Kris Gunnars, BSc, a nutrition researcher and CEO and founder of Authority Nutrition, “On a molecular level, the body functions with an enormously complex set of chemical reactions. These chemical reactions require energy, which is where calories step in.” Different foods have different effects on the body and go through different metabolic pathways before they’re turned into energy. “Some foods can cause hormone changes that encourage weight gain, while other foods can increase satiety and boost the metabolic rate,” says Gunnars. For instance, when fructose enters the liver from the digestive tract, it can be turned into glucose and stored as glycogen. But, if the liver is full of glycogen, it can be turned into fat. Consumed in excess, it can cause insulin resistance, which drives fat gain. Fructose also doesn’t impact satiety, and it doesn’t lower the hunger hormone ghrelin. On the other hand, Gunnars explains, about 30 percent of calories from protein will be spent on digesting it because the metabolic pathway requires energy. In addition, protein may increase levels of fullness and boost the metabolic rate. Increased protein levels may also be used to build muscle, which burns calories around the clock.16

One study showed that diets high in protein and/or low in carbohydrate produced greater weight loss, but “neither macronutrient-specific differences in the availability of dietary energy nor changes in energy expenditure could explain these differences in weight loss.”17 Another study concluded that the body may use calories from low-carbohydrate diets less efficiently than those from low-fat diets, with greater weight loss as a result. In that study, a group of obese volunteers lost 10 percent to 15 percent of their weight by reducing their calorie intake to 60 percent of estimated needs with a carefully controlled diet for 12 years. They were then fed enough calories to maintain their newly reduced body weight through either a low-fat, low-glycemic index (low in readily absorbed sugars and simple starches) or a very-low-carbohydrate diet. Those on the very-low-carbohydrate (very-high-fat) diet burned between 100 and 300 calories more per day than those on the low-fat (high-carbohydrate) diet. The researchers, however, didn’t determine the source of the energy loss, but the results implied that very-low-carbohydrate diets result in more calories wasted in metabolism.18

But, despite studies showing a calorie in is not just a calorie out, the jury is out on this. According to Malden Nesheim, emeritus professor of nutrition at Cornell University, and Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, “Most studies that find significant differences in weight loss in people eating different proportions of protein, fat or carbs rarely last more than six months. Longer-term studies of a year or more seldom show clear advantages of low-carb diets.” And, they say, “Most scientific reviews conclude that a diet of any composition will lead to weight loss if it reduces calories sufficiently.”18

Myth: Slow, gradual weight loss, rather than rapid weight loss, leads to long-term results. Fact: Actually, more rapid and greater initial weight loss has been associated with lower body weight at the end of long-term follow-up. A meta-analysis conducted in 2010 that compared rapid weight loss with slower weight loss found that people with rapid weight loss early on were not more likely to gain back the pounds than people who lost weight gradually.19

Myth: Setting unrealistic goals defeats weight-loss goals.

Fact: While this is a reasonable hypothesis, studies show that setting unrealistic goals does not interfere with weight-loss outcomes. In one study of 314 women whose average age was 51 years, researchers examined whether having a weight-loss experience that lived up to expectations was related to maintenance in a group that successfully lost weight. At study entry, participants had lost 19 percent of their body weight, yet 86 percent of participants were currently trying to lose more weight. Further losses of 13 percent of body weight were needed to reach self-selected ideal weights, with heavier participants wanting to lose more. While the weight loss-related benefits participants achieved did not live up to their expectations, it did not affect subsequent weight maintenance outcomes.20

Myth: Making small, sustained changes in diet and exercise will lead to greater and longer-term weight loss.

Fact: This, again, relies on the “calorie in, calorie out” theory. While it seems to make sense that cutting or burning 3,500 calories over time leads to a pound of weight lost, over the long term, it’s much more complex due to individual variability that affects changes in body composition, as well as balance of food and type of exercise. Studies show that you can’t apply the 3,500-calorie rule when modifications are made over long-term periods because it was derived from short-term experiments performed mostly in men on very-low-energy diets. One study found that people who gradually lost weight over a long period of time only lost about 20 percent as much as would be expected: just 10 pounds, rather than 50, after walking a mile every day for five years.19,21

Myth: Physical education classes reduce obesity in children.

Fact: The types of physical education classes offered in the U.S. have not been shown to reduce or prevent obesity. Three different studies that focused on an increase in the number of days children attended physical education classes found that the effects on BMI were inconsistent across sexes and age groups. 19 One, a meta-analysis of 26 studies, found that school-based physical activity interventions have a positive impact on four of nine outcome measures: duration of physical activity, television viewing, VO2 max and blood cholesterol. However, these interventions had no effect on leisure time physical activity rates, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, BMI and pulse rate.22

Dispelling the Myths Now

Most would not deny that obesity is a serious health problem all over the world. Termed “globesity,” the problem is most acute in prosperous countries. In fact, the U.S. has the distinction of being the world’s fattest nation. But, obesity is also a problem in low- and middle-income countries, and governments worldwide recognize this.

In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) made a political declaration committed to advancing the implementation of the “WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health,” which introduced policies and actions aimed at promoting healthy diets and increasing physical activity in the entire population. WHO also developed the “Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases [NCD] 2013-2020.” Known as the “Global Action Plan,” it will “contribute to progress on nine global NCD targets to be attained by 2025, including a 25 percent relative reduction in premature mortality from NCDs by 2025 and a halt in the rise of global obesity to match the rates of 2010.” In 2016, the World Health Assembly published a report titled the “Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity” that included six recommendations to “address the obesogenic environment and critical periods in the life course to tackle childhood obesity.”23

Yet, even with global efforts, many myths and misconceptions continue to spread, contributing to the rising rates of obesity. Aimed at understanding this epidemic, studies indicate that curbing obesity works best at the individual level, on a case-by-case basis, starting with an understanding of obesity’s factual causes and preventive measures. Unfortunately, it’s just not as simple as calories in/calories out.

References

- Frellick M. AMADeclares ObesityaDisease. Medscape, June 19, 2013. Accessed at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/806566.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, and Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 219, November 2015. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db219.pdf.

- Thaik CM. The Psychology of Obesity. Psychology Today, June 20, 2013. Accessed at www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-heart/201306/the-psychology-obesity.

- Wilson S. The History of BMI. How Stuff Works. Accessed at health.howstuffworks.com/wellness/diet-fitness/weight-loss/bmi4.htm.

- Nainggolan L. New Obesity Guidelines: Authoritative ‘Roadmap’ to Treatment. Medscape, Nov. 12, 2013. Accessed at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/814202.

- An Epidemic of Obesity Myths. “Overweight” and “Obese” Celebrities and Sports Stars. Accessed at www.obesitymyths.com/myth1.1.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Body Mass Index: Considerations for Practitioners. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/BMIforPactitioners.pdf.

- Sifferlin A. Why BMI Isn’t the Best Measure for Weight (or Health). Time, Aug. 26, 2013. Accessed at healthland.time.com/2013/08/26/why-bmi-isnt-the-best-measure-for-weight-or-health/.

- Jeffrey RW and Sherwood NE. Is the Obesity Epidemic Exaggerated? No. British Medical Journal, 2008 Feb 2; 336(7638): 245. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2223031.

- Harvard School of Public Health. Obesity Trends. Accessed at www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesity-trends.

- Legg TJ. Obesity: When Is It Genetic? Healthline, June 6, 2016. Accessed at www.healthline.com/health/obesitywhen-it-genetic#Overview1.

- Sifferlin A. New Genes IDd in Obesity: How Much of Weight Is Genetic? Time, July 19, 2013. Accessed at healthland.time.com/2013/07/19/news-genes-idd-in-obesity-how-much-of-weight-is-genetic/.

- Laidman J. Obesity’s Toll: 1 in 5 Deaths Linked to Excess Weight. Medscape, Aug. 15, 2013. Accessed at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/809516.

- Reinberg S. Is Healthy Obesity a Myth? WebMD, April 30, 2014. Accessed at www.webmd.com/diet/news/20140430/is-healthy-obesity-a-myth#1.

- Rodriguez T. Obesity Associated with Increased Mortality Risk. Endocrinology Advisor, July 14, 2016. Accessed at www.endocrinologyadvisor.com/obesity/mortality-higher-in-obesity/article/509605.

- Gunnars K. Why “Calories In, Calories Out” Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story. Authority Nutrition. Accessed at authoritynutrition.com/debunking-the-calorie-myth.

- Buchholz AC and Schoeller DA. Is a Calorie a Calorie? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, May 2004, vol. 79 no. 5 899S-906S. Accessed atajcn.nutrition.org/content/79/5/899S.full.

- Nasheim M and Nestle M. Is a Calorie a Calorie? PBS, Sept. 20, 2012. Accessed at www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/is-a-calorie-a-calorie.html.

- Casazza K, Fontaine KR, Astrup A, et al. Myths, Presumptions, and Facts About Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 2013; 368:446-454. Accessed at www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMsa1208051.

- Gorin AA, Pinto AM, Tate DF, et al. Failure to Meet Weight Loss Expectations Does Not Impact Maintenance in Successful Weight Losers. Obesity, 2007;15:3086–3090. Accessed at www.academia.edu/19007386/Failure_to_Meet_Weight_Loss_Expectations_Does_Not_Impact_Maintenance_in_Successful_Weight_Losers_.

- Friedman LF. 7 Common Myths About Obesity and Weight Loss. Business Insider, Nov. 30, 2015. Accessed at www.businessinsider.com/obesity-weight-loss-exercise-science-2015-11.

- Dobbins M, DeCorby K, Robeson P, Husson H, and Tirilis D. School-Based Physical Activity Programs for Promoting Physical Activity and Fitness in Children and Adolescents Aged 6-18 (Review). Evidenced-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 4: 1452–1561 (2009). Accessed at www.academia.edu/6212587/Cochrane_review_Schoolbased_physical_activity_programs_for_promoting_physical_activity_and_fitness_in_children_and_ adolescents_aged_6-18.

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Accessed at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en.