Measles: A Patient’s Perspective

- By Trudie Mitschang

WHEN THEIR youngest son Max became ill with measles in 1995, Rüdiger Schoenbohm and his wife, Anke, were naturally concerned. Max was only 6 months old and still too young to have been vaccinated. He spent several days with a high fever that led to serious complications; his lungs got infected, he developed a dry cough and struggled to breathe. “We were worried, of course, but had no clue how serious things actually were,” recalls Rüdiger. “After a few weeks, everything was over. Max had recovered and as spring came around, our vivid, high-energy boy was back. What we did not know back then was that a much more serious complication was on the way.”

WHEN THEIR youngest son Max became ill with measles in 1995, Rüdiger Schoenbohm and his wife, Anke, were naturally concerned. Max was only 6 months old and still too young to have been vaccinated. He spent several days with a high fever that led to serious complications; his lungs got infected, he developed a dry cough and struggled to breathe. “We were worried, of course, but had no clue how serious things actually were,” recalls Rüdiger. “After a few weeks, everything was over. Max had recovered and as spring came around, our vivid, high-energy boy was back. What we did not know back then was that a much more serious complication was on the way.”

Max was in third grade when he began to struggle in math. Initially, his parents thought he was dealing with attention and concentration issues, but that’s when the seizures started. “In October 2004, the first seizure occurred,” explained Rüdiger. “Max would suddenly stop what he was doing and he would just sit and stare. Sometimes for just a few seconds, or other times a minute or more. When the seizure was over, he could not remember anything. We later learned this kind of seizure is called ‘absence.’”

The doctors told the Schoenbohms that sometimes children develop this kind of epilepsy when they are just about to enter puberty. But a short time later, Max underwent an electroencephalogram (EEG) that showed severe abnormalities in his brain. The doctors tried to control the seizures with a special mix of anticonvulsants that minimized the attacks for a few weeks, but then the seizures came back with a vengeance.

“The doctors sent us to one of the best epilepsy centers in Germany where they only needed a few examinations to confirm their worst suspicions: Max was diagnosed with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPe), a late complication of an early age measles infection. SSPe is rare, but fatal — without exception. It was very hard for us to believe they were talking about our bright, vivacious 10-year-old boy.”

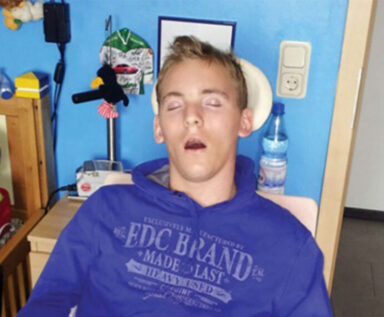

Rüdiger says the family fought hard for a long time, spending nights on the Internet seeking some sort of treatment that would stop the inevitable. They established contacts with medical scientists in India, Turkey and the United States. They imported homeopathic medicine from India. But in April 2006, Max experienced an unexpected brain inflammation that put him into a vegetative state. “Within only hours, he lost everything he had learned during his young life. His last words were: ‘I don’t know who you are.’ It’s going to haunt us for the rest of our lives.”

Heartbreakingly, Max eventually succumbed to his illness in 2014 at age 18. As Rüdiger and his wife reflect on this unthinkable tragedy, they say what drives them crazy is the fact that obligatory vaccination — a policy that still does not exist in Germany — could have protected children like Max from getting infected by measles in the first place. “When it comes to vaccination, parents are not only responsible for their own children. Their decision for or against vaccination may have a significant impact on others! There are proven cases of babies being infected by measles while sitting in a pediatrician’s waiting room.”

As he observes the recent resurgence of measles in the United States (he and his family are living in Florida at the time of this interview), Rüdiger is disheartened by the spike in vaccine hesitancy: “The only protection from measles is vaccination. Had Max not been too young to be vaccinated, he would most likely still be with us today.”

When asked what he would like to say to people who doubt vaccination is safe or effective, he notes that in his experience, people who don’t believe in science and instead follow conspiracy theories are nearly impossible to reach: “Conversations with them tend to lead to a dead end — much like debates about faith or religion. We had many of those discussions back then, until we eventually realized: It’s pointless.”

He adds, however, that it’s a very different story with the large majority of people who are simply uncertain or confused. In those cases, he believes information helps, such as sharing real-life stories of suffering caused by lack of vaccination, showing statistics and reflecting on the past: which diseases have been eradicated through vaccination and how vaccination has been a blessing to humanity for over a century.

“What has proven most effective is authentic storytelling — ideally sharing your own experience, just as we have done for many years and continue to do. I truly believe we were able to convince at least some hesitant parents of young children to vaccinate. There were several articles and television programs that covered Max’s story — even internationally — and we hope it made at least a small difference and will continue to do so today.”