Avian Flu and Human Vaccines: Where Things Stand

Enhancing readiness now can save lives and reduce societal and economic disruption if H5N1 or another outbreak becomes a pandemic. — Jesse L. Goodman, Norman W. Baylor, Rebecca Katz and others1

- By Keith Berman, MPH, MBA

SHORTAGES AND recent spikes in egg prices have boosted public awareness that a “bird flu” is devastating domestic poultry flocks across the country. Since its arrival in the U.S. in January 2022, more than 166 million farmed poultry animals have been sacrificed in an attempt to control the spread of H5N1, a highly pathogenic avian influenza A (HPAI) featuring H5 hemagglutinin and N1 neuraminidase surface proteins (H5N1).*2 Avian flu has infected more than 160 native bird species across all 50 states.3 Carried by migratory birds primarily as a gut virus, H5N1 is now endemic on every continent except Australia.

But much more than the unprecedented scale of this avian influenza outbreak is keeping public health officials and virologists awake at night. Since May 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has received more than 550 reports of HPAI-related illness and deaths in a diverse range of mammals, including cattle, wild and domestic cats, rodents, wild dogs, bears, raccoons, skunks and a number of marine mammals.4

H5N1 avian flu has been spreading around the globe through wild migratory birds since the late 1990s. But this surprising new ability of the virus to “spillover” from birds to mammals has been attributed to a novel H5 variant that originated in Europe, dubbed 2.3.4.4b. A 2.3.4.4b genotype known as B3.13 has infected and caused nonfatal mastitis in dairy cattle in 17 states since early last year.5,6 More recently, spillovers of yet another H5 2.3.4.4b genotype, called D1.1, have been reported in wild birds and, in February and March of this year, in nearly 200 dairy cattle herds.7

* In early March of this year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) additionally reported high mortality in a flock of roughly 46,000 broiler chickens in Mississippi infected with a new highly pathogenic H7N9 avian influenza virus (with version 7 of the hemagglutinin protein and version 9 of the neuraminidase protein). 51

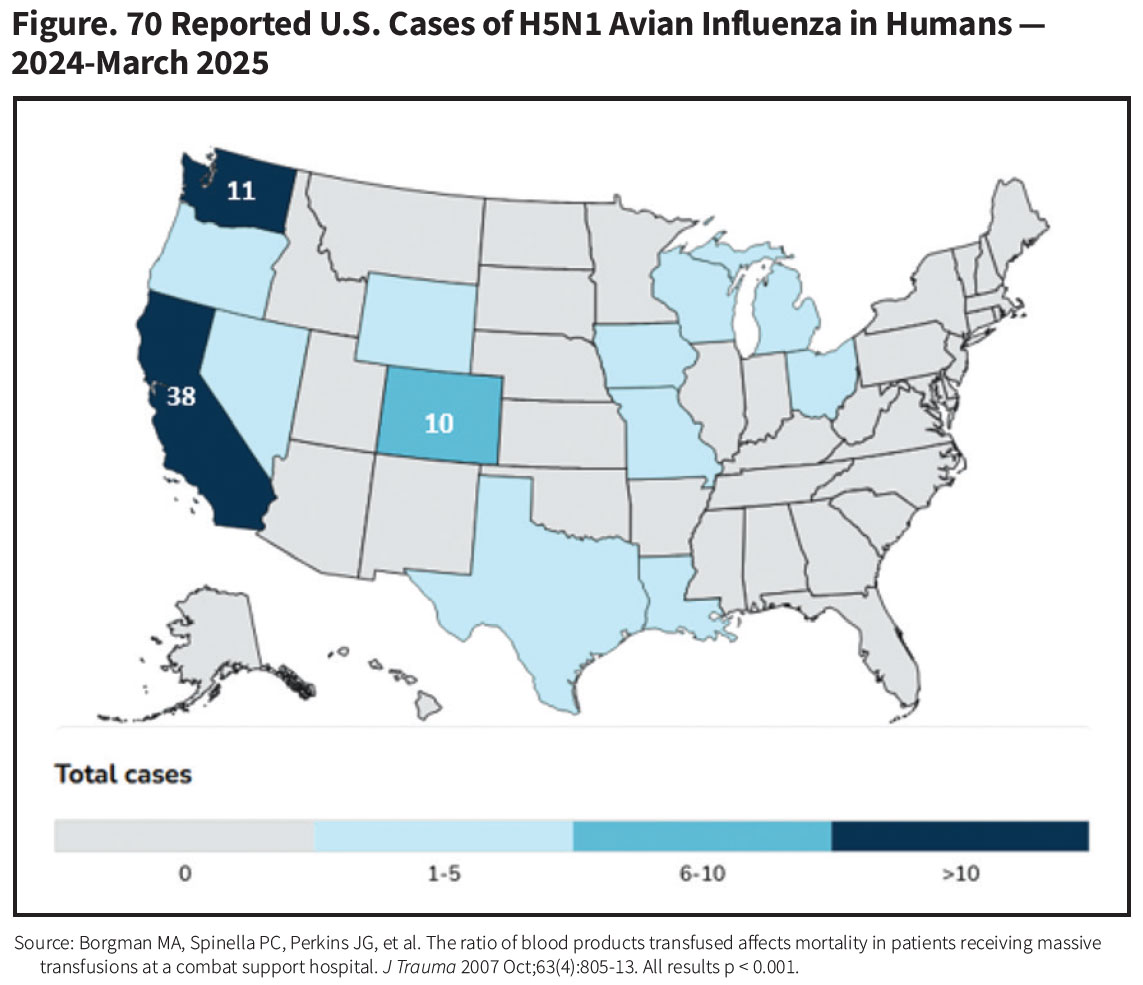

Coinciding with these recent bird-to-mammal spillover events, to date about 70 people working with poultry or dairy cattle have been infected (Figure), most of whom have experienced mild self-limited flu-like symptoms, conjunctivitis or fatigue. But isolated cases of more severe disease have very recently been seen in people infected with the newer D1.1 strain, including a Canadian teen who became critically ill and the first reported U.S. death in an older individual with underlying health conditions.8 “By no means is this Day 1 of a pandemic,” said University of Pennsylvania microbiology professor Scott Hensley, “but this is exactly the scenario we fear.”9

For now, there is no evidence of human-to-human transmission of avian H5N1. Infection and illness risk is currently confined to persons exposed directly to infected birds or cattle. Both the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization rate the risk posed by H5N1 viruses for the general population as low.10 Major changes in the genetic composition of H5N1 would be required for the virus to successfully take up residence and replicate in the upper respiratory tract of humans, where they could be spread by droplets to other humans through sneezing or coughing, or other direct contact.

But experts agree that a human pandemic could happen, as it did in 2009 when an antigenic shift in a porcine H1N1 influenza A virus enabled it to jump to people. That swine flu pandemic caused an estimated 123,000 to 203,000 deaths across 73 countries.11 Further, there is scientific consensus that the global avian flu panzootic is with us to stay; because it is endemic in wild migratory birds, more outbreaks can be expected to occur for the foreseeable future.

Those inevitable outbreaks directly translate into future opportunities for H5N1 to reassort with a different influenza virus strain in the same human or mammalian host to produce a new highly pathogenic flu virus that can be easily transmitted from person to person — a potentially catastrophic pandemic. “Every new infection in an animal and person is like throwing a pair of thousand-sided dice,” said James Lawler, MD, MPH, of the University of Nebraska’s Global Center for Health Security. “It may take a while, but eventually it will come up snake eyes.”12

Government-Stockpiled Bird Flu Vaccines

This scenario became increasingly evident to vaccine experts after the very first outbreak of avian flu in 1997, which took the lives of a three-year-old Hong Kong boy and five others,13 expanded from its origins in China’s Guangdong province to infect wild and domestic birds throughout Asia, Europe and Africa. Over the last two decades, U.S. health authorities contracted with vaccine manufacturers to produce inactivated H5N1 vaccines for storage in the National Pre-Pandemic Influenza Vaccine Stockpile. These stockpiled vaccines are ready, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), “in the event that an H5N1 avian influenza virus develops the capability to spread efficiently from person-to-person resulting in the rapid spread of disease across the globe.”14

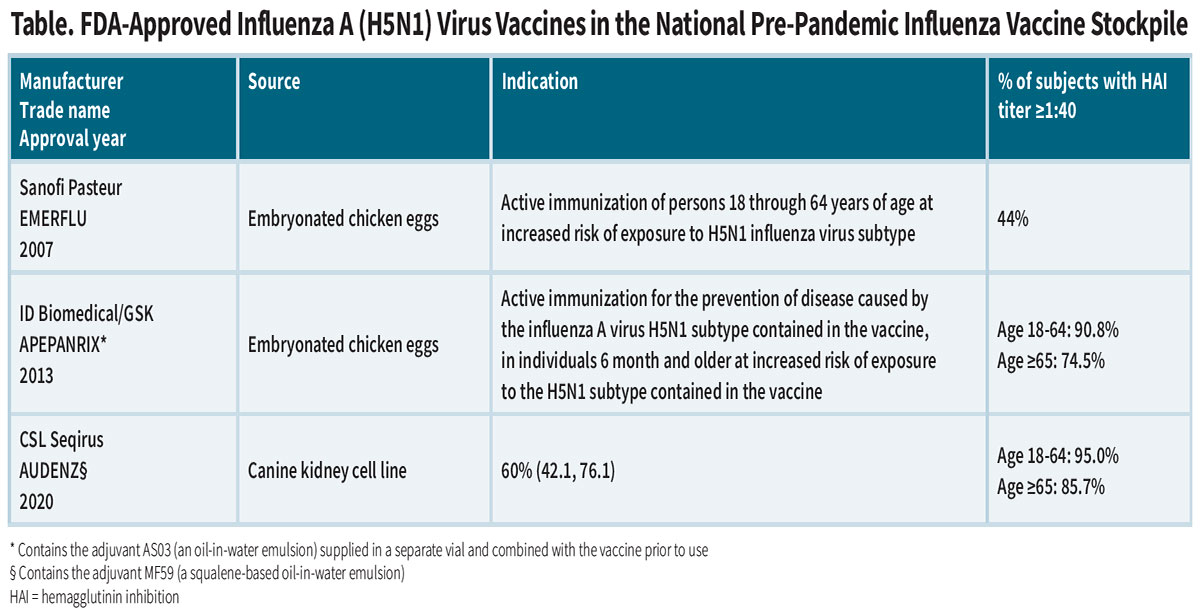

The national stockpile contains H5N1 vaccines from three manu-facturers, propagated in chicken eggs or mammalian cells (Table). But in fact, most are in component form and must go through the final “fill and finish” production stages before final FDA approval for distribution, in the event of a human outbreak, to individuals at increased risk of exposure to H5N1.

The immunogenicity of these “pre-pandemic” whole-virus vaccines was assessed in healthy volunteers by measuring neutralizing hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibody titers and determining the proportion achieving a titer ≥1:40 three to four weeks after the second dose. The vaccines produced by ID Biomedical and CSL Seqirus were likeliest to induce a significant neutralizing antibody response against H5 antigens, but it is unknown how well they might provide protection against serious disease, particularly in infected children and elderly adults.

In mid-2024 amid numerous reports of symptomatic infections in mammals, the federal government placed an order for about 4.8 million doses of CSL Seqirus adjuvanted pre-pandemic vaccine, which was well-matched to the H5 protein decorating the circulating H5N1 virus at that time.

Next: Quickly Deployable mRNA Vaccines

Like vaccines for seasonal influenza A and B, the protective efficacy of an avian H5N1 vaccine is only as good as its match to the ever-evolving hemagglutinin surface protein on the strain that one day manages to overcome the person-to-person transmission hurdle. But as with seasonal flu vaccines, traditional propagation of virus in embryonated chicken eggs or in mammalian cell culture delays the production of inactivated whole virus vaccines by a number of months. In the context of a fast-moving pandemic, this time lost would very likely translate into a cost in human lives.

Fortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has supplied a proven, well-established platform: messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines that can both be quickly updated, manufactured on a large scale and distributed. According to Dr. Hensley, who himself is collaborating on H5N1 vaccine development, “the beauty of mRNA is the ability within a moment’s notice to change the vaccine.”15

Below are some of the more advanced mRNA vaccine development initiatives currently in progress:

GlaxoSmithKline’s GSK-5536522 vaccine. In July 2024, GSK licensed the development, manufacturing and commercialization rights to this H5 mRNA vaccine from CureVac, a German vaccine maker.16 Initiated in 2024, GSK’s Phase I/II placebo-controlled trial is currently recruiting 1,080 healthy adult participants to investigate the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of five dose levels of GSK-5536522 administered in two doses 21 days apart. This study was expected to be completed before mid-year 2025.

Moderna’s mRNA-1018 vaccines. Moderna has completed a Phase I/II clinical study in 1,500 healthy volunteers to generate safety and immunogenicity data for a total of four investigational mRNA-based “pandemic influenza vaccines:” H5N8, H7N9, H5 only and H7 only.17 Last year’s reported jump of avian flu variants from birds to large mammals prompted the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to award the company $176 million in funding last July to accelerate development of these vaccine candidates.

In January, HHS boosted funding to support late-stage development, after trial data showed that two doses of mRNA-1018 consistently induced a rapid, potent and durable immune response in 300 healthy adults. In late May, however, HHS terminated its late-stage development award and the right to purchase pre-pandemic influenza vaccines.

Sanofi’s influenza SP0289 vaccine. In April, Sanofi initiated a Phase I/II dose-ranging study of its second-generation “structurally designed (SD2) H5 mRNA vaccine against potential pandemic influenza viruses. Three dosage levels will be administered to a total of 240 healthy adult subjects to evaluate its safety and immunogenicity. Multiple outcome parameters will be measured, including seroconversion rates and percentages of patients with an HAI titer ≥1:40 or ≥1:80. The study waas expected to be completed in May 2026.

Arcturus Therapeutics’ LUNAR-H5N1 vaccine. With funding support from HHS, last December, San Diego-based Arcturus initiated a Phase I study of LUNAR-H5N1, an investigational self-amplifying mRNA vaccine also identified as ARCT-2304, in 200 healthy adults.18 This trial will evaluate the safety and multiple immune responses to three different dosage levels, including HAI and virus microneutralization.

Unique to Arcturus’ vaccine is its lipid-mediated nucleic acid delivery system, designed to address the rapid degradation of naked RNA when it is introduced into the bloodstream. Similarly to its competitors’ early-stage trials of mRNA vaccines, LUNAR-H5N1 will be administered as a two-dose series in both non-elderly and elderly adults. This study is projected to be completed by the end of 2025.

Additionally, several non-industry laboratories have reported highly encouraging results with investigational mRNA vaccines administered in animal models. Notably, a CDC research team has documented robust neutralizing antibody titers in ferrets immunized with mRNA vaccines derived from a 2.3.4.4b viral variant against both a 2022 avian viral isolate and a 2024 human isolate. Compared to virus-challenged controls, viral loads in vaccinated animals were significantly reduced in the upper respiratory tract, lungs and intestinal tract. Most encouragingly, the mRNA vaccine protected nine of 10 ferrets from a lethal dose of H5N1 virus, whereas all unvaccinated ferrets succumbed to infection. “These results underscore the effectiveness of mRNA vaccines against HPAI A (H5N1), showcasing their potential as a vaccine platform for future influenza pandemics,” the investigators concluded.19

Preparing for the Next Pandemic

Experts agree that the unprecedented persistent global circulation of the H5N1 avian flu virus — and now its expanded host range to include agricultural animals and wild mammals — has created conditions that could result in a new global pandemic. “Although the virus does not currently pose a direct pandemic threat to humans, it’s concerning,” said Caitlin Rivers, PhD, MPH, at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.20

Indeed it is. But thanks to proactive investments in vaccine stockpiling and aggressive new vaccine research and development, industry is better prepared than ever before to help providers and public health authorities minimize the adverse health impact of a new avian flu pandemic if or when it happens.

References

1. Goodman JL, Baylor NW, Katz R, et al. Prepare now for a potential H5N1 pandemic. Science (letter). 2025 Mar 6;387(6738):1047.

2. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. APHIS confirms H7N9 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in a U.S. flock. Accessed at www.aphis.usda.gov/ news/program-update/aphis-confirms-h7n9-highly-pathogenic-avian-influenza-hpai-us-flock.

3. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza in wild birds. Accessed at www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/wild-birds.

4. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Mammals. Last modified March 12, 2025. Accessed 3/17/2025 at www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/mammals.

5. Caserta LC, Frye EA, Butt SL, et al. Spillover of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N2 virus to dairy cattle. Nature 2024 Jul 25;634:669-676.

6. U.S. Department of Agriculture. HPAI Confirmed Cases in Livestock (through April 4, 2025). Accessed at www.aphis.usda. gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/hpai-confirmed-cases-livestock.

7. CIDRAP. USDA confirms spillover of 2nd H5N1 avian flu genotype into dairy cattle. Feb. 5, 2025. Accessed at www.cidrap.umn. edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/usda-confirms-spillover-2nd-h5n1- avian-flu-genotype-dairy-cattle.

8. Louisiana Department of Health. LDH reports first U.S. H5N1- related human death. Jan. 6, 2025. Accessed at ldh.la.gov/news/ H5N1-death.

9. STAT. H5N1 bird flu virus in Canadian teenager displays mutations demonstrating virus’ risk. Nov. 18, 2024. Accessed at www.statnews.com/2024/11/18/bird-flu-pandemic-h5n1-virus-mutations-canada-genomic-analysis.

10. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Risk to people in the U.S. from highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) viruses as of Feb. 28, 2025. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/cfa-qualitative-assessments/php/data-research/h5-risk-assessment. html.

11. Fineberg HV. Pandemic preparedness and response — lessons from the H1N1 influenza of 2009. New Engl J Med 2014 Apr 3;370:1335-1342.

12. Fiore K. Here’s what RFK Jr. got wrong about H5N1 bird flu. MedPage Today. March 19, 2025. Accessed at www. medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/birdflu/114731.

13. Yuen KY, Chan PK, Peiris M, et al. Clinical features and rapid viral diagnosis of human disease associated with avian influenza H5N1 virus. Lancet 1998;351:467-471.

14. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Monovalent Vaccine, Adjuvanted, manufactured by ID Biomedical Corporation — Questions and Answers. March 23, 2018. Accessed at www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/influenza-h5n1-virus-monovalent-vaccine-adjuvanted-manufactured-id-biomedical-corporation-questions.

15. Park A. TIME. Scientists are racing to develop a new bird flu vaccine. Jan. 2, 2025. Accessed at time.com/7203820/h5n1-new-bird-flu-vaccine-update.

16. CureVac. GSK and CureVac to restructure collaboration into new licensing agreement. July 3, 2024. Accessed at www.curevac. com/en/gsk-and-curevac-to-restructure-collaboration-into-new-licensing-agreement.

17. ClinicalTrials.gov. A study of mRNA-1018 pandemic influenza candidate vaccines in healthy adults. NCT05972174. Accessed at clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05972174?term=mRNA-1018&rank=1.

18. Arcturus Therapeutics. Safety and immunogenicity of self-amplifying RNA pandemic influenza vaccine in adults. Accessed at clinicaltrials.gov/search?term=ARCT-2304.

19. Hatta M, Hatta Y, Choi A, et al. An influenza mRNA vaccine protects ferrets from lethal infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus. Sci Transl Med 2024 Dec 18;16(778):eads1273.

20. NBC News. A bird flu vaccine from Moderna is in early stages of development. July 2, 2024. Accessed at www.nbcnews.com/ health/health-news/bird-flu-vaccine-moderna-early-stages-development-rcna159978.