Immunodeficiency in Older Adults

Seven case studies unveil some of the immunodeficiencies affecting seniors.

- By E. Richard Stiehm, MD

Primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIs) are common, believed to affect one in every 1,200 persons.1 And, secondary immunodeficiencies, occurring as a result of age, illness, injury or medication, are considerably more common than PIs.2

In fact, every person has survived the immunodeficiency of the newborn, and the immunodeficiency of the aged, termed immunosenescence, will affect most of us in our senior years. Immunosenescence, which occurs in patients over age 60, includes new-onset, pre-existing and overlooked PIs, as well as secondary immunodeficiencies. Following are seven case studies that will examine these, the latter of which will include the immunodeficiency of older adults, their immune profile risk and some ways to delay aging, preserve immunity and live a long time.

Case 1: Shingles and Lymphopenia in a 69-Year-Old Woman

Mary, age 69 and retired from teaching, was doing well, enjoying gardening and walking her dog, when she developed painful shingles of the chest and upper arm. Nine years previously, she had received a shingles vaccine. The shingles occurred shortly after a prolonged viral respiratory infection with wheezing, which was treated with a course of steroids. Physical examination, except for the vesicular rash, was unremarkable. Her white blood count was 4,800 cells/uL with 15 percent lymphocytes. Immunoglobulins were normal, and antibodies to varicella were detectable but low. T and B cell subsets disclosed a CD3 total T cells of 450/uL (low), CD4 helper T cells of 85/uL (very low), CD8 cytotoxic T cells of 350/uL, CD19 B cells of 105/uL and CD16/56 natural killer cells of 72/uL. An extensive work-up for infectious disease was negative, including HIV by antibody and polymerase chain reaction testing. T cell proliferative studies were normal. Valacyclovir was given with rapid improvement. The varicella antibody titer increased dramatically, and she returned to her usual state of good health after three weeks.

Diagnosis: Idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia (ICD)

Comment: ICD is a heterogenous illness first identified in 1992, when widespread lymphocyte subset phenotyping was conducted on people at risk for HIV/AIDS but who were not infected.3 Other apparently well patients, also negative for HIV, were then identified with CD4 levels less that 300 cells/uL, most without major illnesses or other immune abnormalities.4,5 Several ICD patients are older than 40 years, and some, like this patient, are over 60 years. Laboratory stories show only slight impairment of cellular immunity.

ICD patients are also identified following opportunistic infections with varicella/zoster Cryptococci and human papilloma virus.4 Others are identified with autoimmune disease such as Behcet’s disease, vasculitis or thrombocytopenia. In a few patients, genetic testing has identified mutations linked to other immunodeficiencies.5 The prognosis is guarded with a long-term mortality of 15 percent among 40 patients.

Case 2: Pneumonia and a Chest Mass in a 72-Year-Old Man

Thomas was in good health until a few years ago, when he developed a cough with sinusitis. He had a complete examination six years ago, including a normal chest X-ray. In the last few days, his cough worsened, and he developed a fever of 102 degrees Fahrenheit. His doctor noted some post-nasal drip and a few wheezes. Laboratory studies showed a slightly elevated sedimentation rate (31 mm/hour) but a normal complete blood count and chemistries.

A chest X-ray disclosed a symmetrical 6 cm in diameter anterior mediastinal mass. A CT scan suggested a thymic tumor. Further immune studies disclosed CD3 total T cells of 1,525 cells/uL, CD4 helper T cells of 550/uL, CD8 cytotoxic T cells of 780/uL and CD19 B cells of 85/uL (low). Immunoglobulins included an IgG of 220 mg/dl, IgM of 45 mg/dl and IgA of 30 mg/dl. Pneumococcal titers (despite a Pneumovax vaccine one year previously) were non-protective.

A complete thymectomy was performed, which revealed a spindle cell thymoma. The patient made an uneventful recovery. He was started on intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) therapy with clinical improvement.

Diagnosis: Immunodeficiency with thymoma (Good syndrome)

Comment: Immunodeficiency with thymoma was first described by Robert Good in 1954.6 The disorder primarily affects individuals between 40 years and 70 years. It is the only form of a primary late-onset antibody deficiency with low B cells. Most patients have mild to moderate hypogammaglobulinemia, variable defects of T cell immunity and a propensity to autoimmunity.7 Hypogammaglobulinemia is present in about 5 percent of all patients with thymomas.

Thymomas are also associated with myasthenia gravis and aplastic anemia, and, as in the immunodeficiency of Good syndrome, are not reversed by thymectomy. The prognosis of patients with Good syndrome is favorable with IVIG therapy, unless the thymic tumor is malignant.

Case 3: A 74-Year-Old Woman on Immune Globulin Therapy for 24 Years

Jane, a 74-year-old screenwriter, was diagnosed with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) 20 years previously because of frequent infections and a bout of pneumonia. She had an IgG of 310 mg/dl, IgM of 32 mg/dl and IgA of 18 mg/dl. Total B cells were normal, but there were decreased numbers of switched memory B cells (CD19+, CD27+, IgD-, IgM-). Antibody titers to prior vaccines were non-protective. T-cell numbers and function were normal. She was started on monthly intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), and four years ago, she switched to weekly subcutaneous IG infusions given at home.

In the last few months, Jane developed increasing fatigue, abdominal pain, intermittent diarrhea and a 10-pound weight loss. Her hemoglobin was 9.8 gm/dl, white blood count was 6,800 cells/uL and a normal differential. IgG was 705 mg/dL, IgM was 25 mg/dL and IgA was 20 mg/dL. The sedimentation rate was 64 mm/hr, and Coombs’ test was negative. Stool was positive for blood.

A colonoscopy showed patchy infiltrates in the distal colon compatible with Crohn’s disease. She was started on sulfasalazine and a tapering course of steroids with clinical improvement.

Diagnosis: CVID with Crohn’s disease

Comment: CVID is the most common PI requiring lifelong IG therapy.8 The usual age of onset is between ages 20 years and 45 years, but it can present in children and older patients. Most patients live a normal life as long as they receive IVIG therapy. The outlook for prolonged survival is good with careful follow-up; the survival after 40 years is over 90 percent. The exception to this favorable outlook are patients with complications such as chronic lung disease, autoimmune disease, gastrointestinal or hepatic disease and malignancy; these patients have a 40-year survival of 42 percent compared with a 95 percent survival for CVID patients with infections only.9 Accordingly, all CVID patients must be monitored regularly for these complications.

Case 4: An Unrecognized Immunodeficiency in a 72-Year-Old Man with Seizures and Intellectual Disability

Steve, age 72, was a resident at a facility for mentally challenged adults ever since his caretaker brother died two years before. With an IQ of 72, Steve could manage the tasks of daily living but could not hold a job. He had successful heart surgery in the first year of life leaving him with a surgical scar but a well-functioning cardiovascular system.

He was brought to the emergency room because of a non-febrile seizure following a bout of gastroenteritis with diarrhea. Physical examination indicated short stature (5 feet, 2 inches), slight microcephaly, indistinct speech, a midline thoracic surgical scar and a systolic heart murmur. Blood tests revealed hypocalcemia. An endocrinologist diagnosed late-onset hypoparathyroidism. A chromosome analysis revealed a 22q11.2 deletion. Immunoglobulins and lymphocyte subsets were normal. A head and neck surgeon identified a small cleft palate. He was started on calcium and vitamin D without recurrence of his seizures.

Diagnosis: DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome) with normal immunity and late-onset hypoparathyroidism.

Comment: After Down syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality (one per 6,000 live births).10 Most patients have a heterozygous chromosome deletion of 22q11.2, resulting in defects of the pharyngeal pouch system. The classic triad includes a hypoplastic thymus with cellular immunodeficiency, cardiac anomalies and hypocalcemia due to hypoparathyroidism. Distinctive morphologic features include low-set ears, ocular hypertelorism, palatal defects, tapered fingers and micrognathia.

The cellular immunodeficiency of DiGeorge syndrome can be profound (for example, the complete DiGeorge syndrome resembles severe combined immunodeficiency). In greater than 95 percent of cases, the immunodeficiency is mild and occasionally nonexistent.

Asymptomatic adult DiGeorge syndrome patients are often diagnosed because their child has DiGeorge syndrome. Other adults are identified because of cardiac conditions, speech and swallowing abnormalities, endocrinopathies or psychosocial problems. Many are in institutions, attending psychiatric clinics or in the criminal justice system.11 The average IQ of adults with DiGeorge syndrome is 70. It may be the PI most often overlooked.

Case 5: A Common New-Onset PI in a 75-Year-Old Male

Edward, a 75-year-old physician, was healthy all of his life. He was up to date on all his vaccines, including the 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine (Pneumovax) given 10 years ago. But in the last year, he developed headaches, persistent sore throats, chronic sinusitis and purulent nasal discharge. His doctor found bilateral maxillary sinusitis on Waters view X-rays and started him on antibiotics. He improved with a two-week course of amoxicillin, but symptoms recurred when the medication was stopped.

Laboratory studies showed a normal complete blood count and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 21 (borderline high). IgG was 630 mg/dl, IgM was 134 mg/dl, IgA was 22 mg/dl and IgE was 45 IU/ml. Pneumococcal antibody titers showed protective titers to two of 23 serotypes. Following a repeat Pneumovax vaccine, five of 23 were protective. He was diagnosed with selective antibody deficiency (SAD).

The 13-serotype protein conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (Prevnar) was given; repeat titers showed that 10 of 23 were now protective, all of which were serotypes present in Prevnar. He was given a six-week course of antibiotics that cleared his sinusitis and then placed on prophylactic Azithromycin 250 mg three times weekly. This controlled his infections, and he has done well on this treatment.

Diagnosis: SAD

Comment: SAD, also termed impaired polysaccharide responsiveness, is probably the most common PI. It is particularly common in children 2 years to 6 years old and probably in individuals older than 60 years. SAD is characterized by frequent infections, normal immunoglobulins, intact cellular immunity, deficient antibody responses to polysaccharide vaccines, particularly Pneumovax, but normal responses to protein vaccines such as Prevnar, tetanus or measles.12

SAD is present in most infants for the first two years of life and was the impetus to develop protein-conjugate vaccines for pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae infections.

The characteristic clinical features are recurrent respiratory infections such as sinusitis, otitis and bronchitis. While younger children under age 6 years may recover spontaneously, late-onset adult SAD is usually permanent, and may sometimes be the first manifestation of a global antibody deficiency such as common variable immunodeficiency. The incidence of SAD increases gradually after age 60 years, suggesting that it is a feature of immunosenescence. SAD may be a component of other PIs, notably DiGeorge syndrome, selective IgA or IgM deficiencies, or combined immunodeficiencies.

Diagnosis is established by a diminished response to a majority of the serotypes in the Pneumovax vaccine (e.g., failure to develop a protective response — 1.3 ng/ml or higher).13 Treatment is antibiotics for each infection, or prophylactically, along with administration of two doses of the Prevnar vaccine. A few patients develop serious infections (pneumonia, mastoiditis) and may require immune globulin therapy.

Case 6: A Secondary Antibody Deficiency in a 68-Year-Old Man

Pedro is a 68-year-old retired house painter. On a routine blood count at age 65, he had a white blood count of 18,200 cells/uL with 72 percent lymphocytes. Physical exam revealed a few enlarged cervical nodes and a slightly enlarged spleen. A hematologist, after an extensive work-up including a bone marrow analysis, diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and since he was asymptomatic, recommended close observation only.14 Six months ago, Pedro developed increasing fatigue, chronic bronchitis and sinusitis. His white blood count was 28,500 cells/uL with 82 percent lymphocytes, hemogloblin was 6 g/dL, IgG was 520 mg/dl, IgM was 52 mg/dl and IgA was 42 mg/dl. He was started on fludarabine and rituximab, as well as amoxicillin for his sinusitis. After six months of therapy, Pedro’s hemoglobin had increased to 12 g/dL, and his white blood count normalized. Because of persistent sinusitis and bronchitis, he was given a Pneumovax vaccine. One month later, his IgG was 250 mg/dl, IgM was 40 mg/dl and IgA was 45 mg/dl. Pneumococcal titers showed only one of 23 serotypes was protective. He was started on intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) therapy, with two infusions of 500 mg/kg three days apart, followed by repeat infusions of 500 mg/kg every four weeks. His IgG levels increased from 250 mg/dL to 720 mg/dL, but his B cells remained low. His sinusitis and bronchitis improved on this treatment.

Diagnosis: CLL with hypogammaglobulinemia, probably aggravated by rituximab

Comment: CLL is the most common leukemia in adults, accounting for 25 percent of all leukemias. It occurs primarily in older adults and is more common in males. About 10 percent of CLL patients have hypogammaglobulinemia at presentation, which increases to 70 percent as the disease progresses. This is hastened and worsened by rituximab therapy, a monoclonal antibody to CD20 B lymphocytes, the precursor of the plasma cells that synthesize serum immune globulins. The hypogammaglobulinemia of rituximab is usually reversible when the drug is stopped.15 Lifelong IG therapy is effective in limiting infections in these patients. Some patients have subtle T cell defects that magnify the immunodeficiency.

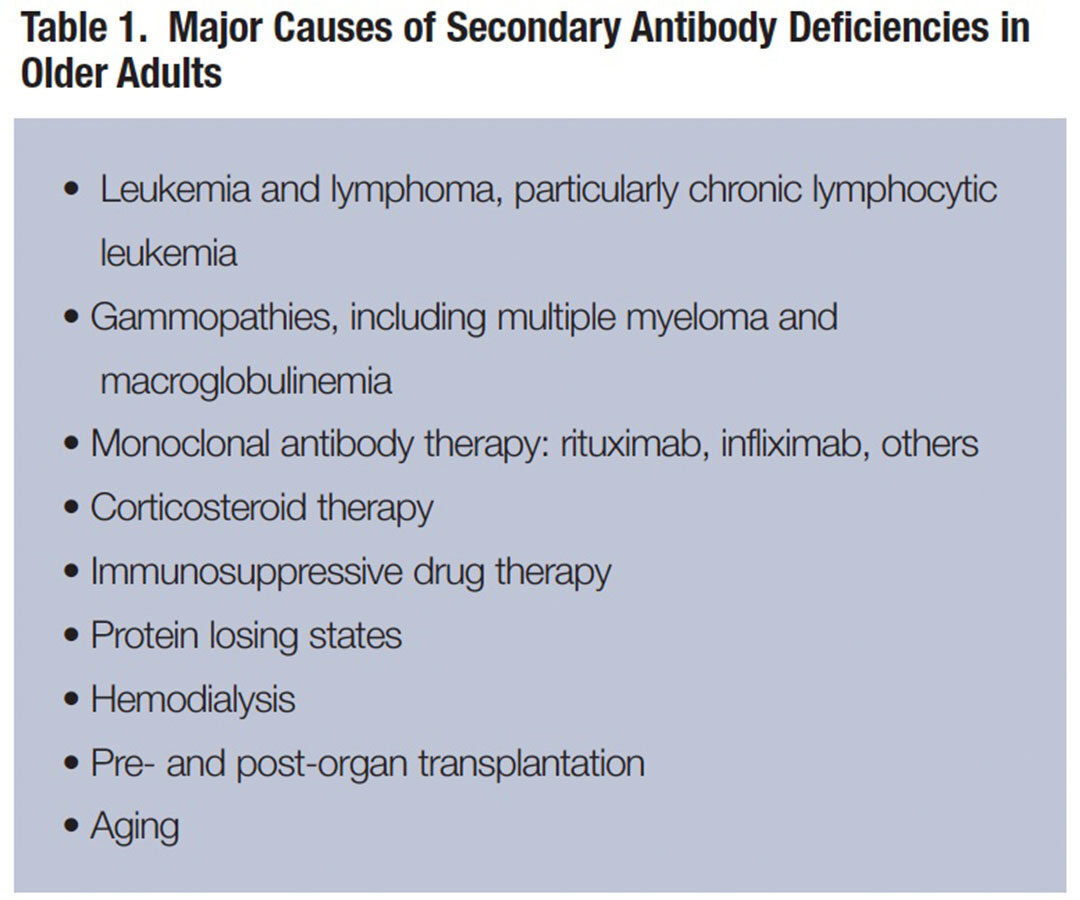

CLL and other secondary antibody immunodeficiencies in older subjects are more common than PIs.16 Some of the major causes of secondary deficiency requiring IG therapy are listed in Table 1. Many more have T-cell deficiencies associated with cancer, steroids or other immunosuppressive therapy.

Case 7: An 88-Year-Old Hyperactive Man with a Worried Spouse

The wife of 88-year-old Arthur, despite his protests, brought him to the doctor because of his lifestyle. He had the habit of standing on a box, waving his arms and grimacing (smiles, frowns, joy, etc.). He continued this behavior for two or more hours at a time but never seemed tired or bored. He attracted a crowd to witness his behavior, and most were delighted with his antics. His wife worried about his health; she was sure he would become fatigued and catch something from the surrounding crowds. But he refused to stop, so she took him to his doctor.

He told the doctor that he was fully employed, exercised four hours a day, didn’t smoke or drink, and was neither fat nor thin. His vaccines were up to date. The physical exam was unremarkable. Laboratory tests showed a normal complete blood count, chemistry panel and C-reactive protein. He had protective titers to tetanus, pertussis, pneumococci and varicella.

An immune profile risk assessment indicated a favorable profile: normal CD4 and CD8 cells, and a CD4:CD8 ratio of greater than 1.0.16,17 B cells were 320/uL, CD8+CD28-cells (memory cells) were normal, and an antibody titer to cytomegalovirus (CMV) was negative. Individuals with these features are likely to live to be 100.18

Diagnosis: Very healthy orchestra conductor

Comment: This man had the right demographics: Married, no bad habits, neither fat nor thin, well-immunized and an occupation that he loved and that fully engaged both his mind and body. He was an orchestra conductor.

Orchestra conducting is an occupation known for its longevity18 as exemplified by Arturo Toscanini conducting almost to the time of his death at age 87.

With advancing age, the immune system weakens, particularly the T cell system. The T cells are principally responsible for immunosurveillance (i.e., removing damaged cells that predispose to infection, cancer or autoimmunity). Alterations of the immune system with aging include thymic atrophy, decreased CD4 cells, increased CD8 cells, decreased naïve and increased memory cells, and elevated antibody titers to CMV.19 The latter suggests that immunosenescence is related to CMV reactivation, resulting in increased CMV cytotoxic T cells and elevated CMV antibody responses, to the detriment of responses to other antigens. CMV reactivation causes chronic inflammation leading to tissue and organ damage.

Efforts to reduce the effects of aging are disappointing, although caloric restriction and moderate exercise have proven modest benefits. Dietary supplements (vitamins, probiotics, etc.) are not of proven benefit. The active ingredient in red wine (resveratrol) increases the life span of yeasts, worms and flies but not humans.20

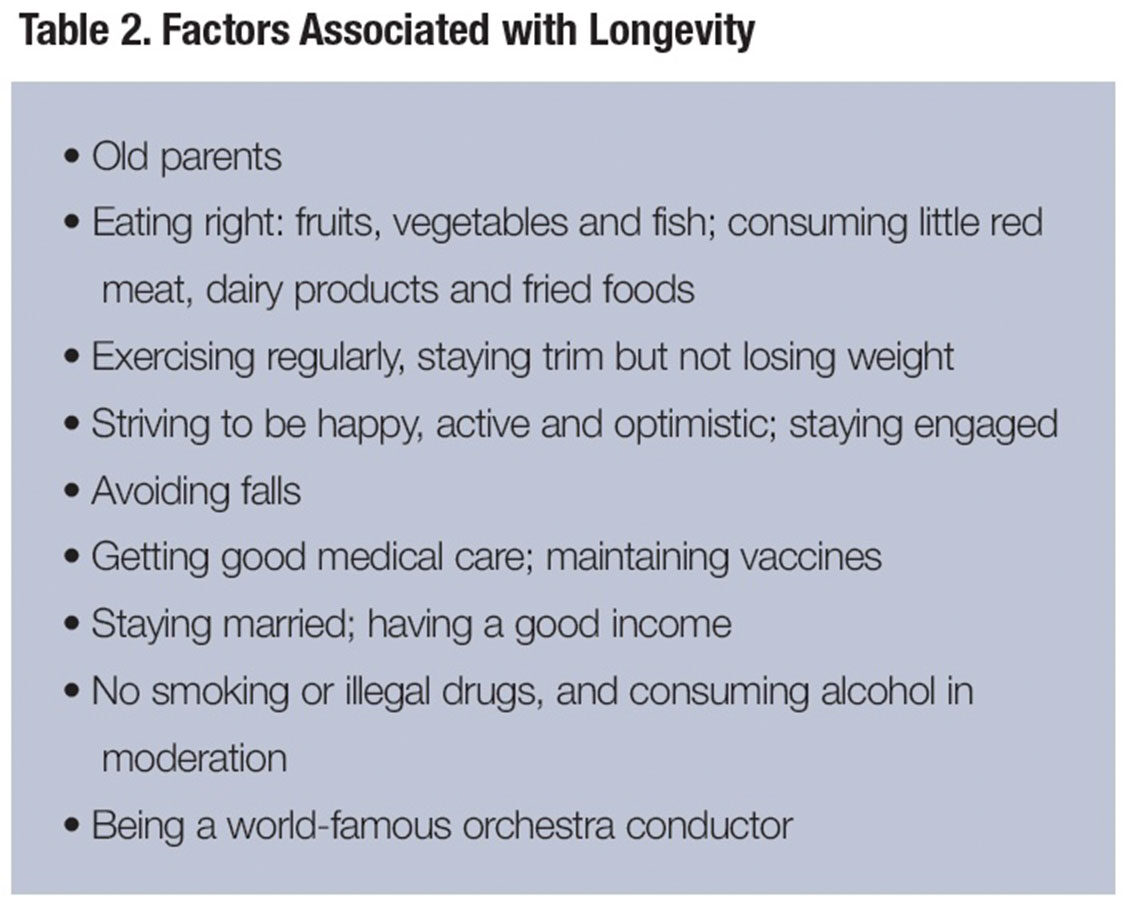

So if you want to live to be 100 with an intact immune system, first live to be 99. In the meantime, see Table 2 for some suggestions.

References

- Boyle JM and Buckley RH. Population Prevalence of Diagnosed Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases in the United States. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 2007 27:497-502.

- Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA, et al. Secondary Immunodeficiencies, in Immunologic Disorders in Infants and Children, 5th Edition. Elsevier/Saunders, Philadelphia, 2004, pp687-964.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. T Lymphocyte Depletion in Persons without Evident HIV Infection. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 1992 41:451.

- Regent A, Autran B, Carcelain G, et al. Idiopathic CD4 Lymphopenia: Clinical and Immunologic Characteristics and Follow-Up of 40 Patients. Medicine, 2014 93:61-72.

- Zonios D, Sheikh V, and Sereti I. Idiopathic CD4 Lymphocytopenia: A Case of Missing, Wandering or Ineffective T Cells. Arthritis Research Therapy, 2012 14: 222-28.

- Good RA. Agammaglobulinemia — A Provocative Experiment of Nature. Bulletin of the University of Minnesota Medical Foundation, 1954 26:1-19

- Malphettes M, Gerald L, Galicier L, et al. Good Syndrome: An Adult-Onset Immunodeficiency Remarkable for Its High Incidence of Invasive Infections and Autoimmune Complications. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2015, 61 e13-9.

- Resnick ES and Cunningham-Rundles C. The Many Faces of the Clinical Picture of Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2012 12: 595-601.

- Resnick ES, Moshier EL, Godbold JH, and Cunningham-Rundles C. Morbidity and Mortality in Common Variable Immune Deficiency Over 4 Decades. Blood, 2012; 119:1850-7.

- Botto LD, May K, Fernhoff PM, et al. A Population-Based Study of the 22q11.2 Deletion: Phenotype, Incidence, and Contribution to Major Birth Defects in the Population. Pediatrics, 2003; 112:101-7.

- Vogels A, Schevenels S, Cayenberghs R, et al. Presenting Symptoms in Adults with the 22q11 Deletion Syndrome. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 2014 57: 157-162.

- Ambrosino DM, Umetsu DT, Siber GR, et al. Selective Defect in the Antibody Response to Haemophilus Influenzae Type B in Children with Recurrent Infections and Normal Serum IgG Subclass Levels. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 1988; 81:1175.

- Orange JS, Ballow M, Stiehm ER, et al. Use and Interpretation of Diagnostic Vaccination in Primary Immunodeficiency: A Working Group Report of the Basic and Clinical Immunology Interest Section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2012 130 (3 Suppl):S1-24.

- Dhalla F, Lucas M, Chuh A, et al. Antibody Deficiency Secondary to Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Should Patients Be Treated with Prophylactic Replacement Immunoglobulin? Journal of Clinical Immunology, 2014 34: 277-82.

- Roberts DM, Jones RB, Smith RM, et al. Immunoglobulin G Replacement for the Treatment of Infective Complications of Rituximab-Associated Hypogammaglobulinemia in Autoimmune Disease: A Case Series. Journal of Autoimmunity, 2015 57: 24-9.

- Agarwal S and Busse PJ. Innate and Adaptive Immunosenescence. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, 2010 104: 283-90.

- Strindhall J, Nilsson BO, Lofgren S, et al. No Immune Risk Profile Among Individuals Who Reach 100 Years of Age: Finding from the Swedish NONA Immune Longevity Longitudinal Study. Experimental Gerontology, 2007 42: 753-61.

- Barondess JA. How to Live a Long Time: Facts, Factoids and Descants. Transactions of the American Clinical Climatological Association. 2005,116-77-89.

- Pawelec G, McElhaney, JE, Aiello AR, et al. The Impact of CMV Infection on Survival in Older Humans. Current Opinion in Immunology, 2012:24: 507-11.

- Baur JA, Ungvari, Z, Minor RK, et al. Are Sirtuins Viable Targets for Improving Healthspan and Lifespan? Nature Reviews, 2012 11: 443-461.