Stroke Prevention: A Patient’s Perspective

- By Trudie Mitschang

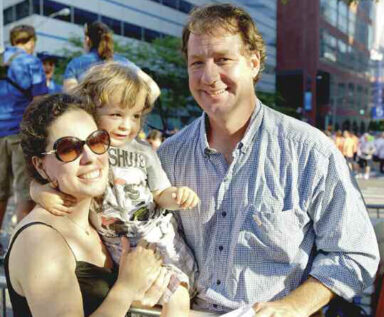

THE DAY BEGAN like any other day. Eric Jordan’s young son, Gabriel, woke up crying at 5:30 a.m., and as a doting dad, Eric scrambled out of bed to comfort him. But, from the moment his feet hit the floor, it was clear this day would prove to be anything but ordinary. In a matter of minutes, Eric was writhing on the floor, and his wife, Christina, was frantically calling 911. At age 41, Eric was in the throes of a massive ischemic stroke.

Waking Up Speechless

Numb on one side and unable to speak or focus, Eric was rushed by paramedics to Columbia University Medical Center/New York Presbyterian Hospital’s primary stroke care center. Although Eric arrived at the hospital within the critical three-hour window required to receive the tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) clot-busting drug, it proved ineffective in dissolving his blood clot. In a race against time, interventional neuroradiologist Dr. Daniel H. Sahlein was called in to perform a life-saving surgical procedure using a Solitaire Flow Restoration Revascularization Device. This mechanical thrombectomy device restores blood flow and retrieves clots in patients experiencing acute ischemic stroke. Although it required two attempts, Dr. Sahlein successfully removed the large blood clot in the left middle cerebral artery of Eric’s brain. In many ways, Eric was fortunate; if his young son had not awakened him, he might have died in his sleep. If paramedics had not rushed him to a skilled stroke care center, he might not have been treated in time. Thankful to be alive, Eric was nevertheless devastated when he woke up to a new reality: he’d lost the ability to speak. “How ironic is it to become an opera singer who cannot speak?” asks Eric. “I felt like a cave man unable to pronounce my Italian, German or Russian. I could not even remember my music.”

The Road to Recovery

According to the American Stroke Association, ischemic stroke accounts for about 87 percent of all cases and occurs as a result of an obstruction within a blood vessel supplying blood to the brain. The interrupted blood flow deprived Eric’s brain of oxygen, which caused cells to die. In Eric’s case, the affected part of his brain was the left hemisphere, the part that manages right-sided motor skills, as well as receptive and expressive language. Statistically, one in four stroke survivors experience a language impairment called aphasia, and, unfortunately, Eric was one of them. A mere two years after embarking on his career dream of singing with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, it appeared his singing career was over. “I went from singing at the Met to being unable to recall the alphabet song,” recalls Eric. “As frightening as it was, I vowed that I would never let fear stop me from becoming a better husband and father. I was determined to recover, no matter what.”

Despite the dire prognosis, Eric began therapy within the first few weeks of his stroke, but progress was slow. He felt like he had an “iron tongue” that needed to be untied. Then, in a positive ironic turn, Eric discovered that while he struggled relearning to speak clearly, the ability to sing was returning quickly. He later learned singing involves different parts of the brain than speaking does, so while his speech remained impaired, his singing gift began to thrive. “This experience has taught me patience,” says Eric. “I have moderate-to-serious aphasia, which makes it hard for me to read, write or say what I mean, as well as apraxia, the inability to execute purposeful movements, so it takes patience for me to communicate and make any sense. Basically, my mind needs to slow down enough to let my tongue catch up.”

Fighting through the frustration and discouragement, Eric surprised everyone by returning to the opera stage a mere six weeks after his stroke, with his wife, parents and doctor sitting proudly in the audience.

Advocacy for Others

Like many people who survive a life-threatening illness, Eric has taken time to reflect on his life’s work and purpose. After reading an inspirational book titled Wherever You Go, There You Are by Jon Kabat-Zinn, Eric discovered the art of mindfulness and meditation, a practice he credits with helping him regain his equilibrium. After discussing his newfound passion with his neighbor, a yoga instructor, the pair teamed up and founded a “wellness ensemble,” a nonprofit whose goal is to use therapeutic movement and music to help stroke survivors and others with brain injuries. Eric says his goal is to train a team of performers that can attend stroke camps and clinics to teach patients how to use music and movement to facilitate healing. In addition to those recovering from stroke, the program is proving helpful for Alzheimer’s patients and children with autism. “We based our program on the findings of UCLA neurology professor Dr. Jeffrey Saver,” says Eric. “We discovered that singing, movement and percussion were all vital components when it comes to helping people regain lost motor skills.”

Eric’s life post-stroke is a busy one, and in many ways, it is a “new normal.” While he is still contracted to sing at the Met through the spring of 2015, his passion for giving back and speaking about stroke recovery has made his schedule these days especially hectic. “Strokes impact people of all ages and from all walks of life,” explains Eric. “If what I do inspires someone to stretch their brain for the greater good, I am thankful. I’m well-armed with patience, a good sense of humor and a desire to help others. That’s what keeps me going.”