Update on Measles

Once eradicated in the U.S., measles is now on the rise due to a growing mistrust of public health guidance, but it is highly preventable with vaccination.

- By Jim Trageser

FOR MOST AMERICANS who are 70 and older, measles is remembered as a childhood disease that everyone got once while growing up — much like chicken pox and mumps — and then, they were immune. It was one of many rites of passage on the road to adulthood.

Even so, although the vast majority of American kids who got measles recovered no worse for the wear, not all were so fortunate. While complications were rare, out of the three to four million kids who got measles in the United States each year, between 400 and 500 died of the disease. Another some 1,000 developed a chronic disability when measles spread to the brain and caused encephalitis or other complications.1

Today, thanks to a series of increasingly effective vaccines introduced beginning in 1963, measles in the United States is rare — not as rare as it was in the year 2000, when measles was declared eliminated from the United States since there had been no documented cases for a full 12 months — but still rare.2 Globally, however, measles remains a leading cause of preventable childhood death, with the World Health Organization reporting some 107,000 fatalities in 2023.3

Of course, as a nation of immigrants, as well as a major international tourist destination and global trade hub, the United States regularly is bombarded with new infections of all types, and measles is no exception. There was also the widely publicized study that purported to show a link between a popular measles vaccine and autism that tragically led many parents to avoid inoculating their children against the disease, even after the study was shown to be completely fraudulent and was withdrawn by the publisher.

This combination of a regular influx of new measles viruses brought to our shores by visitors and newcomers alike, as well as a growing number of unvaccinated young Americans, has led the United States to suffer from one of the largest measles outbreaks in a generation this year — a mere quarter century after declaring measles eliminated. (In 2019, there were 1,274 cases, the most since 2000. By comparison, there were only 285 reported cases in the United States in 2024.) However, in the spring of 2025, there were more than 480 cases in 21 states.4 That statistic has since grown, and as of June 5, 2025, there were 1,088 reported and confirmed cases in 33 jurisdictions in the U.S., resulting in three deaths.5

It is little surprise that the overwhelming majority of those who have contracted measles this spring were unvaccinated.

What Is Measles?

Measles is an infectious disease caused by the measles virus (Morbillivirus hominis, or MeV), which can live only in human beings.1 Measles, also known as rubeola, is distinct from German measles, or rubella. In fact, the viruses that cause the two diseases are not even classified in the same phylum.

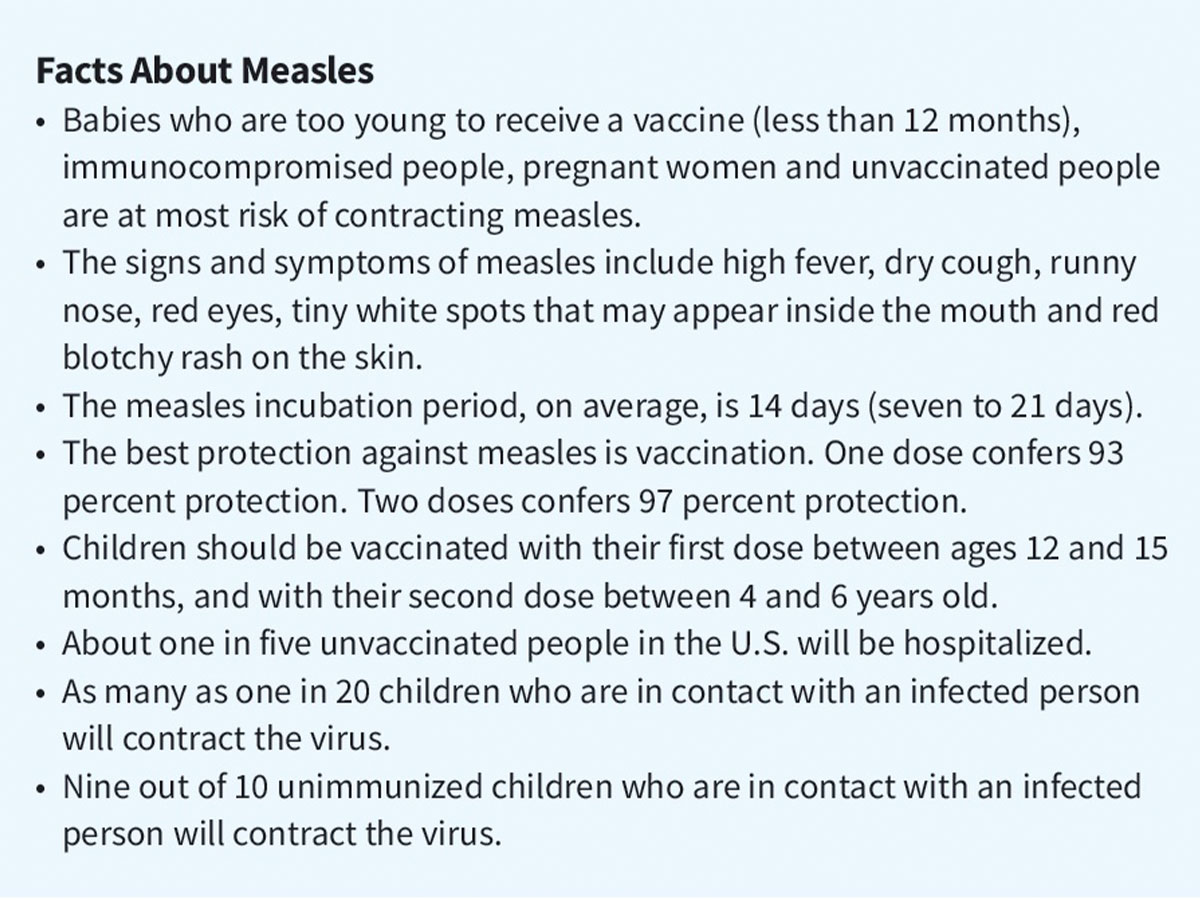

Despite the skin spots that gave measles its name, the disease is in fact a respiratory tract disease. During an active infection, the virus primarily resides in a patient’s nose and throat,6 and it is spread through the air when an infected person exhales, coughs, sneezes or speaks and an unvaccinated person inhales it. The measles virus can live outside the host body in droplets in the air for up to two hours, making it one of the most highly contagious diseases known. Studies have shown that nine out of 10 unimmunized people who are in direct contact with an infected person will contract the disease.7

Researchers believe measles developed out of rinderpest, an infectious viral disease that affected cattle. Although rinderpest was successfully eradicated globally in 2011,8 it is thought that a variant had jumped to humans in the centuries before the rise of the Roman Empire. When that variant became the distinct virus that today only infects humans is open to debate, with researchers placing the date in a range from 700 B.C. to 800 A.D.9

By the ninth century A.D., Persian physician Muhammad Ibn Zakariya Al-Razi had written a paper differentiating smallpox and measles, which until then had been thought to be the same disease.

Measles acquired its current English name from the Middle Dutch word masel for “blemish,” referring to the distinctive skin rash.

Symptoms and Progression of Measles

Symptoms of measles will generally appear between one and two weeks after infection, and will last 10 days or so in most patients. The first symptom is usually a high fever, followed by a sore throat, dry cough, a runny nose and inflamed eyes.10 After two to three days, there may also be tiny white spots inside the mouth. A few days after that, the distinctive skin rash will begin, usually along the hair line on the face, and then spreading down through the chest, arms, abdomen, legs and, finally, the feet. At this point, the patient’s temperature can spike as high as 104 degrees Fahrenheit. The rash will begin to clear after a week, and generally is gone within 10 days of onset.

Individuals who contract measles will be contagious for about a week, beginning about four days before the rash appears.

Complications from Measles

While most patients will see the above progression and resolution, in some, measles can prove to be lifealtering and even fatal. Children under the age of 4 years, adults over age 20 and the immunocompromised are at highest risk of developing serious complications.11

The most common complications are ear infections and bronchitis. In serious cases, ear infections can lead to hearing loss and even deafness. Encephalitis (when the measles virus attacks the cells in the brain) occurs in about one out of 1,000 measles cases.12 Encephalitis can also lead to deafness, as well as intellectual disability.

Pregnant women who contract measles are at elevated risk of maternal death, as well as spontaneous abortion or the child dying in the uterus. In other cases, the infection will cause the child to be born blind.

As the measles virus attacks cells of the immune system, post-measles patients can be more susceptible to secondary bacterial infections,12 which may last for weeks and even years in some patients, and in serious cases, can lead to death. Secondary bacterial infections are responsible for many of the cases of pneumonia in measles patients.

Other serious but rare complications that can arise from a measles infection include:

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM): inflammation of the brain and/or spinal cord13

- Measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE): a complication that can affect the immunocompromised within a year of measles infection, leading to a fatal inflammation of the brain14

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE): a rare, fatal progressive brain inflammation that usually appears seven to 10 years after the initial measles infection15

(See the Patient Profile on p.46.)

Diagnosing and Treating Measles

Measles is diagnosed by either a blood test that finds the measles-specific antibody or a nasal swab that detects measles RNA.

There is no cure for an active measles infection. However, if an unvaccinated patient or a patient with a mildly compromised immune system knows or strongly suspects he or she has been exposed to measles and can seek treatment within 72 hours, a vaccine given in that time may still prevent infection or, at the least, result in milder symptoms.16 Those exposed to measles who seek treatment within six days of exposure may be treated with intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) to help their immune systems ward off the virus.17 Even patients with a severely weakened immune system can benefit from IVIG.

Measles is treated by easing symptoms with fever and pain reducers, rest and liquids. Secondary bacterial infections caused by measles’ attack on the immune system are treated with antibiotics targeting the type and area of infection, with the lungs (bronchitis, pneumonia) and ears among the most frequent locations for these infections.

Other complications are treated according to the specific condition and symptoms.

Encephalitis treatment consists of lowering the inflammation in the brain with drugs, including steroids or IVIG.

The much more rare ADEM will generally manifest within a few weeks of the infection, with a range of symptoms, including fever, headache, fatigue, numbness in the extremities, muscle weakness or difficulty swallowing. A diagnosis is made through imaging of the brain, and treatment is similar to treatment for encephalitis.18

MIBE generally occurs within a year of infection, affects the immunocompromised and is generally fatal. Treatment is comfort-based. SSPE tends to occur seven to 10 years after infection, but treatment will be the same as for MIBE — keeping the patient as comfortable as possible.

Preventing Measles

Given the potentially fatal complications associated with measles, preventing it is the best course of action.

The first measles vaccine was introduced in 1963 by John F. Enders, PhD, who used an attenuated form of the virus. In 1968, Maurice Hilleman, PhD, introduced an improved vaccine that used an even weaker form of the virus to further reduce risk to patients.2 In 1971, the combined MMR (measles, mumps and rubella [German measles]) vaccine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients 12 months and older, and became a standard part of the childhood immunization program.19

With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announcing a major push in 1978 to eradicate measles in the United States within four years, vaccination campaigns ratcheted up, and by 1981, the number of children contracting measles had plummeted by 80 percent.2 A 1989 outbreak of measles that affected many who had been inoculated led to a recommended second dose of the MMR vaccine.

The Autism Scare

Just two years before measles was eliminated in the United States, a British physician, Andrew Wakefield, and 12 colleagues published a paper in the Feb. 28, 1998, edition of The Lancet, Britain’s leading medical journal, claiming to have found a causation between the MMR vaccine and autism. Given the rise in the number of children diagnosed with autism (which is still not wholly understood), the paper naturally created a media firestorm and led to tens, maybe hundreds, of thousands of parents opting out of the MMR vaccine for their children.

Other researchers almost immediately questioned the sample size of the study (only a dozen children), and subsequent studies were unable to replicate Wakefield’s results. By 2004, 10 of Wakefield’s 12 co-authors had withdrawn their names from the study and said there was no causal link.20 In February 2010, The Lancet issued a full retraction of the paper. As additional evidence of outright fraud continued to come to light, Wakefield was eventually banned from practicing medicine.

But the damage was done: A quarter-century later, a study found that most parents who decline to have their child receive the MMR vaccine continue to cite a fear of autism.21

Current Vaccines

There are currently two types of measles vaccines approved by FDA for use in the United States, and several brands.

The MMR vaccine is available in two versions: M-M-R II and PRIORIX. Two doses are recommended for both infants, older children and adults. With infants, the first dose should be administered between 12 and 15 months, and the second between 4 and 6 years. For older patients, the two doses should be given at least 28 days apart.22

The second type of measles vaccine adds inoculation against varicella, or chickenpox, and is popularly known as MMRV (often sold under the ProQuad brand name). This can be administered only to children between the ages of 12 months and 12 years. It should be given at the same interval as MMR: first dose between 12 and 15 months, and the second dose between 4 and 6 years.

In addition, adults who were vaccinated between 1963 and 1968 should consider a booster since some early variants of the vaccine were not as effective.23

It is also important to note that since the measles vaccine uses a live, albeit weakened, variant of the virus, patients who are seriously immunocompromised should generally not receive either the MMR or MMRV vaccine.24

There are occasional complications that can arise from measles vaccines, although these are extremely rare.

Looking Ahead

Until measles is eradicated globally, even nations such as the United States with a strong immunization program are likely to continue experiencing measles outbreaks. The best way to protect patients is to encourage them to receive the measles vaccine.

Repeated testing has shown that the FDA-approved MMR and MMRV vaccines are safe and effective. However, vaccine hesitancy is now ingrained in popular culture due to The Lancet article, as well as other recent events. Listening to parents’ fears, and providing them clear, nonjudgmental feedback about the overall risks and benefits is the best way to allay their concerns.

As more outbreaks occur, it is likely that parents who initially thought that avoiding the MMR vaccine was a low-risk proposition to protect their children will come to realize there are also serious risks that come with avoiding the vaccine.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Overview of Measles. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. History of Measles. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html.

- World Health Organization. Measles. Accessed at www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles.

- Donlevy, K. Measles Outbreak Surges 360% with 483 Cases in 21 States — Most Coming from Texas. New York Post, March 29, 2025. Accessed at nypost.com/2025/03/29/us-news/measles-outbreak-hits-483-cases-in-21-states-most-in-texas.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Cases and Outbreaks (as of April 4, 2025). Accessed at www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How Measles Spreads. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/measles/causes/index.html.

- Milstone, A, and Maragakis, L. Measles: What You Should Know. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed at hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/measles-what-you-should-know.

- Ochmann, S, and Behrens, H. How Rinderpest Was Eradicated. Our World in Data, Sept. 30, 2019. Accessed at historyofvaccines.org/history/measles/overview.

- History of Vaccines. Measles. Accessed at historyofvaccines.org/history/measles/overview.

- Mayo Clinic. Measles. Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/measles/symptoms-causes-syc-20374857.

- Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention. Measles Symptoms and Complications. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/measles/signs-symptoms/index.html.

- Kondamudi, N, and Waymack, J. Measles. StatPearls, Aug. 12, 2023. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448068.

- Ali, D, Detroz, A, Gorur, V, et al. Measles-Induced Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in a Non-Vaccinated Patient. European Journal of Case Reports in Internal Medicine, April 6, 2020. Accessed at pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7279905.

- Mathieu, C, Ferren, M, Jurgens, E, et al. Measles Virus Bearing Measles Inclusion Body Encephalitis-Derived Fusion Protein Is Pathogenic after Infection via the Respiratory Route. Journal of Virology, April 3, 2019. Accessed at pmc.ncbi.nih.gov/articles/PMC6450100.

- Medline Plus. Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis. Accessed at medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001419.htm.

- Mayo Clinic. Measles Diagnosis. Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/measles/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20374862.

- Kohlmaier, B, Holzmann, H, Stiasny, K, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of an Intravenous Immune Globulin (IVIG) Preparation in Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) Against Measles in Infants. Frontiers in Pediatrics, Dec. 2, 2021. Accessed at pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8675579.

- Cleveland Clinic. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Accessed at my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14266-acute-disseminated-encephalomyelitis-adem.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) Vaccine Safety. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/vaccines/mmr.html.

- Rao, TS, and Andrade, C. The MMR Vaccine and Autism: Sensation, Refutation, Retraction, and Fraud. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 2011 Apr;53(2):95-96. Accessed at pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3136032.

- Novilla, ML, Goates, M, Redelfs, A, et al. Why Parents Say No to Having Their Children Vaccinated Against Measles: A Systematic Review of the Social Determinants of Parental Perceptions on MMR Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines, 2023 may 2;11(5):926. Accessed at pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10224336.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles: Vaccination. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/measles/vaccines/index.html.

- National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Frequently Asked Questions About Measles. Accessed at www.nfid.org/resource/frequently-asked-questions-about-measles.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Routine Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/hcp/recommendations.html.