Education and Storytelling: An Antidote to Parental Fears About Vaccine Safety

- By Keith Berman, MPH, MBA

What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.

— Ecclesiasties 1:9

THE YEAR WAS 1908 and, late in life, a wealthy 67-year-old industrialist named John Pitcairn found himself drawn to a newfound interest. Pitcairn’s son Raymond had suffered an adverse reaction after receiving a childhood vaccination some years earlier. More recently, citing their religious belief in homeopathic medicine, Pitcairn and fellow church members resisted efforts by Pennsylvania health officials to vaccinate them during a local smallpox outbreak. But Pitcairn most ardently opposed vaccination for yet another reason: He believed it was wrong for government to force people to act against their will.1

This energetic Scottish immigrant, who had parlayed his elementary school education into a huge personal fortune in steel and railroads, knew how to make things happen. He personally bankrolled a national conference of vaccination opponents, which was held in Philadelphia in October 1908. This event served as the springboard for Pitcairn and his friend and fellow businessman Charles Higgins to cofound the Anti-Vaccination League of America.1

As they lobbied state legislatures to repeal compulsory vaccination laws and distributed numerous polemical pamphlets regaling readers with graphic descriptions and photographs of victims allegedly disfigured, blinded and killed by vaccination, public health authorities were busy deploying smallpox vaccine to control outbreaks. The number of reported cases of the much more deadly of two smallpox variants, variola major, fell from an average of 5,100 cases per year between 1900 and 1905 to 400 per year between 1906 and 1909; deaths plummeted from just over 800 per year to 33.2

By the 1920s, Pitcairn and Higgins were gone, but the effects of anti-vaccination activism by them and others lingered on. Just 10 states had compulsory vaccination laws, while 28 had none and four actively prohibited such laws. Reported smallpox case rates make it clear which side was in the right: There were 6.6 cases per 100,000 residents in the 10 states with compulsory vaccination laws, and 66.7 and 115.2 cases per 100,000 in the 28 states with no laws and prohibitions, respectively.2 By 1930, vaccination programs had eradicated variola major, one of the most terrible scourges in human history, in the United States.

Understanding Today’s “Anti-Vaxxers”

Laws and regulations created by government at the local and state levels dictate limits on how we drive, what protective gear motorcyclists must wear, at what age we can buy alcohol, and where smokers can and cannot smoke — all intrusions on personal choice justified by volumes of public health and safety research. But state laws making vaccinations compulsory for our children, whom we commit to nurture and protect, represent a unique test of our democratic process. It turns out that, much like a century ago, there are those who are simply unwilling to place their trust in government and its scientific and public health experts.

Not unlike the anti-vaccine dissidents of a century ago, people most vehemently opposed to childhood vaccination often have broader underlying reasons. Some are ideologically opposed to government mandates or restriction of personal liberties. Some have religious-based objections. Some eschew conventional medicines in favor of “natural” health treatments. And some have a blanket distrust for pharmaceutical manufacturers or the integrity of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) vaccine safety oversight.

But ardent “anti-vaxxers” comprise a very small minority of the millions of parents who this year will choose not to allow their children to receive their scheduled vaccines. Most are simply fearful parents who have been exposed to anti-vaccine propaganda, with its terrifying warnings and tales about children who suddenly developed any of a panoply of neurological, neurobehavioral, autoimmune and other serious disorders following vaccination.

Unfortunately, today’s band of anti-vaccination zealots have been joined by a modern-day version of the infamous snake-oil salesmen of the late 19th century. A prime example is an osteopathic physician and web entrepreneur named Dr. Joseph Mercola. Parents who stumble upon or are referred to Mercola’s vast website will find astonishing anti-vaccine statements like this one:3

“Vaccinations are very neurotoxic and have been associated with many neurological disorders, like encephalopathies, epilepsy, convulsions, ADD, LD, autism, mental retardation, depression, anxiety, CNS disorders, paralysis, Guillain-Barré Syndrome, nerve deafness, blindness and SIDS. The neurological disorders associated with vaccinations are diverse and numerous. Vaccinations lower IQ as well as contribute to the overt mental disorders and neurological diseases listed here.” [A list of 17 disorders follows.]

Baseless inflammatory misinformation of this nature is the dangled bait for uninformed parents already prone to unquestioningly embrace it, but a pop-up quickly reveals this Internet huckster’s real agenda: “Here’s your chance to start enjoying my high-quality natural products.”

Disease Outbreaks: The Upshot of Declining Vaccination Rates

As has been widely reported, some of the lowest childhood immunization rates — far below the 95 percent rate commonly cited as a goal for herd immunity — are found in relatively highly educated and health-focused communities. The seeming paradox is that these are just the kinds of parents one would expect to be most enthusiastic about protecting their children from these serious childhood illnesses. But this is not the case for three related reasons:

1. Thanks to the success of U.S. childhood immunization policy over a number of decades, parents today are typically unfamiliar with these diseases or their potential seriousness. Prior to the availability of a measles vaccine, about 500,000 people were infected annually with measles in the U.S. Serious health complications were not uncommon, especially in children under 5 years of age. About one in every 1,000 people with measles developed brain swelling, which often led to brain damage. One to two out of 1,000 died, even with the best care.

But since the 1963 introduction of the vaccine and 1994 implementation of the Vaccines for Children program that now provides free vaccines for all children,∗ measles was declared eliminated in 2000, meaning that no new cases originated domestically. Few new parents have seen or heard about anyone with the measles. The same can be said for most other childhood illnesses all but eradicated by a universal childhood vaccination policy: Notwithstanding a local outbreak affecting their own community, most parents have little or no awareness of their potentially serious threats to health.

2. Publicized toxin-disease links make it easy to stir up fears about vaccine safety. Well-educated and more health-conscious parents tend also to be more aware that there are real causal associations between toxins created by human activity — certain plasticizers in food containers, high mercury levels in fish, chemical contaminants in the water supply — and serious diseases, including cancers. These legitimate concerns have propelled a growing market for organic and natural foods. On the flip side, this same sensitivity can readily be exploited to push baseless theories and disproven claims linking vaccine products to serious health conditions, particularly those such as autism that have no clear cause.

3. Anti-vaccination campaigns addressing children have a powerful psychological impact. No parent wants to be an accomplice to an action that could seriously harm his or her child. The more extreme the allegations against vaccines, the more that caution seems merited. And again, while anti-vaccination slogans and propaganda today echo the florid statements of a century ago, today the diseases themselves are virtually nowhere to be found — except when an isolated outbreak happens to hit.

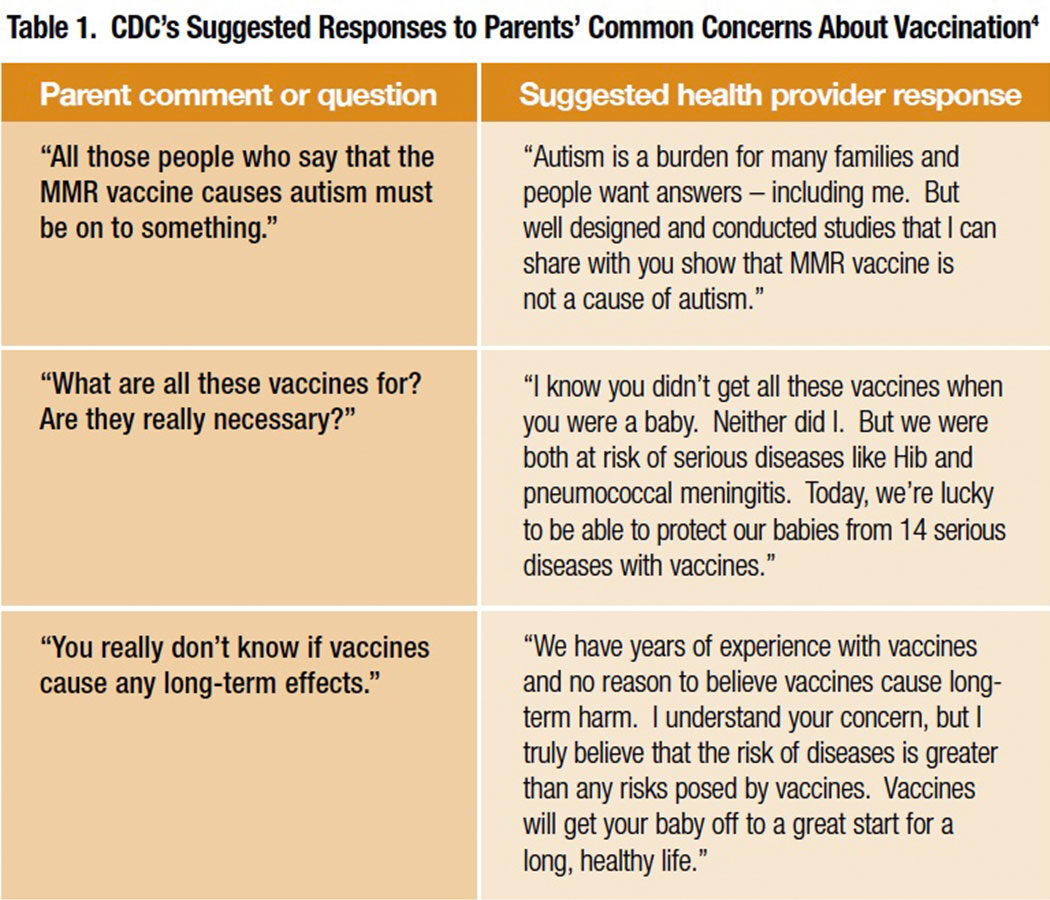

Of course, plenty of information is available to help providers make parents aware of the risks of not immunizing their children against measles, mumps, rubella, polio, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus and other diseases on the pediatric immunization schedule. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) brochure for providers titled “Talking with Parents about Vaccines for Infants” offers helpful suggested responses to common concerns expressed by parents (Table 1).4 Materials developed by CDC in collaboration with pediatric and family practice specialty societies can be found on the Internet, downloaded and printed with just a few clicks.5,6

Many of these resources require parents to read fairly dry or lengthy written items. For example, another CDC document for parents headlined “If You Choose Not to Vaccinate Your Child, Understand the Risks and Responsibilities”7 is single-spaced and two pages long. Unfortunately, some people are easily distracted, or become overwhelmed, or don’t effectively absorb information when they try to read it. Others with a skeptical nature simply may not trust written materials.

That is where the healthcare provider, and the provider’s relationship built over time with each family, comes in.

Taking Measure of Parents’ Cognitive and Learning Styles

Ordinarily when discussing a treatment with a patient, there is a disease or condition connected to it. The patient is motivated to manage the problem, usually has no preexisting biases, and looks to the clinician as the authority. In part, childhood vaccination turns this typical interaction on its head. There is no disease present (and thus little tangible motivation). Some parents inevitably arrive with a negative frame of reference primed by exposure to alarmist misinformation about the safety of vaccines.

Fortunately, parents have already placed their trust in their child’s pediatrician or family physician to do the right thing for their child’s health. They are prepared to listen. The challenge for the physician and allied health staff is to try to gauge what kind of information, presented in what way, might work best. Behavioral experts have suggested a variety of preferred cognitive styles, with labels such as denialist (“I don’t care what the data show; I don’t believe the vaccine is safe”), innumerate (“a one-in-amillion risk sounds high”), heuristic (“I remember Guillain-Barré syndrome happened in 1977 after flu vaccines; that must be common, so I’m not getting a flu vaccine”) and analytical (“I want to see the data so I can make a decision”). More basically, a CDC guidance points out that presenting too much science will frustrate some parents, while too little will frustrate others.4

But regardless of any given parent’s cognitive leanings, educators the world over know that illustrative diagrams and stories are key to effective communication.

Herd Immunity Told in Graphics and Stories

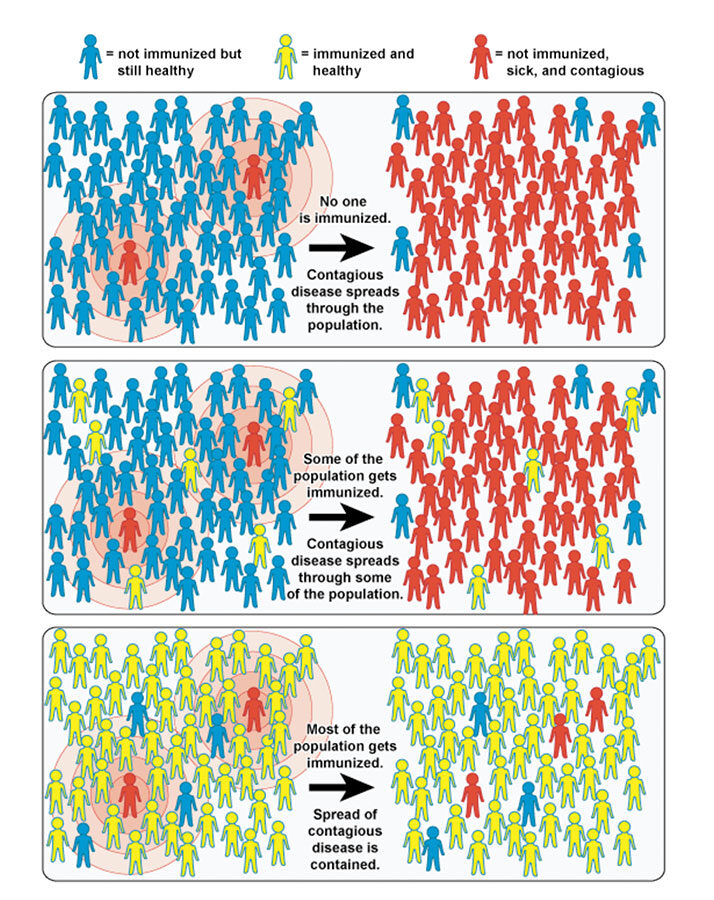

There is one last “easy out” for those parents who have heard the statistics, seen the images and disease descriptions, and received the reassurances about safety, but are still hesitant. They can decide to skip vaccination for their child and rely on herd (community) immunity, betting that the protective immune resistance of other vaccinated children will act to shield their unvaccinated child from exposure. Essentially, these are vaccination “freeloaders” who want to put their faith in herd immunity to protect their child without committing to join the herd.8 So how does one go about clarifying the importance of herd immunity while also harnessing it to persuade these parents to get on board?

Below are two focused educational tactics that may achieve this — and more. The first introduces two important considerations that parents may not have thought about: 1) the ever-present risk that infected visitors from overseas will start a community outbreak, and 2) the threat that an unvaccinated child presents to others with congenital or treatment related immunodeficiency disorders. The second of these tactics — a story of a serious measles outbreak in Ireland — dovetails with the history of how the alleged link between measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination and autism (since disproven by a number of large studies9,10) came to be: Callous research fraud by a nownotorious former United Kingdom physician named Andrew Wakefield.

Present a graphic representation of herd immunity, which illustrates how it works and why herd immunity breaks down when the community vaccination rate drops significantly below 95 percent (Figure 1). The authoritative Oxford Textbook of Public Health defines herd immunity as “the relative protection of a population group achieved by reducing or breaking the chains of transmission of an infectious agent because most of the population is resistant to infection through immunization (or prior natural infection).”11 Depending on the parent receiving it, a verbal characterization like this may or may not confer some idea of how herd immunity works. Herd immunity is too important a concept to trust mere words to communicate it to parents questioning the need to vaccinate their child. Coupling the words and a simple graphic representation of a small “herd” of human beings can serve to bring the concept to life.

Graphics similar to those in Figure 1 can be used for more than just explaining why it’s so important to achieve as close to a 100 percent vaccination rate as possible. A stick figure can be circled or highlighted to represent a child with leukemia whose immune system has been weakened by chemotherapy, or a pregnant woman at risk for contracting rubella and giving birth to a baby with permanent brain or heart damage, or an elderly person in the family with diminished resistance to seasonal influenza virus. The point is that the game of hoping that herd immunity will protect one’s non-vaccinated child has far higher stakes: That child who becomes infected presents a very serious threat to the health of many others with impaired defenses against the infective pathogen.

With a pen or marker, the clinician-educator can also draw a new stick figure just outside the “herd” that represents an infected child or adult visiting the U.S. from abroad. The measles genotype of infected persons during a well-publicized outbreak traced to Disneyland in Southern California perfectly matched the genotype circulating in 14 countries, including the Philippines, where there was a large recent outbreak.12 This finding strongly suggests that a foreign visitor may have been the source. Foreign tourists account for a significant share of the many millions of people streaming through airports and visiting U.S. theme parks and other large public venues each year. An unvaccinated child visiting a nearby theme park may contract the infection from an international visitor and show up as usual the next week in the school classroom. With a simple drawing or a few strokes on an illustration depicting herd immunity, parents can be visually shown how disease can be propagated by children who have not received their protective vaccines. The lower the community vaccination rate, the faster and farther it can spread. A brief visually-aided presentation like this reduces the wiggle room for the parent first inclined to be a vaccine “freeloader.”

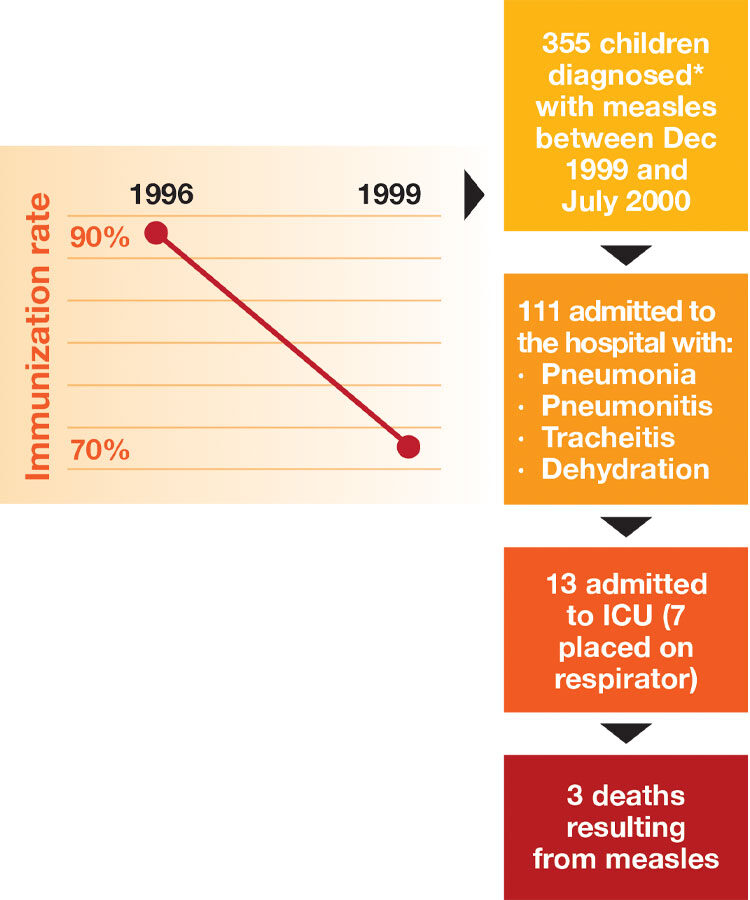

Share a real story about a disease outbreak attributable to a suboptimal immunization rate. Because of the special circumstances leading up to it, an outbreak of measles that occurred in Ireland between December 1999 and July 2000 (Figure 2) is an excellent example to use. In February 1998, The Lancet published a fraudulent 12-patient case series, authored by a London gastroenterologist named Andrew Wakefield, that asserted a strong temporal association between MMR vaccination and onset of chronic enterocolitis and behavioral symptoms later diagnosed as autism. Later investigations found that Wakefield had entirely falsified the data, and had been secretly paid nearly $700,000 by personal-injury lawyers trying to make a case that the MMR vaccine was unsafe.13

The fraudulent Wakefield report was retracted six years later, long after the damage to public confidence about MMR vaccine safety had been done. Ireland’s national MMR immunization rate fell from more than 90 percent prior to the Wakefield Lancet report to 79 percent two years later. In North Dublin, the epicenter of the outbreak where 355 measles cases were reported over a seven-month period, it had fallen to less than 70 percent. As summarized in Figure 2, more than 100 of these children had to be admitted to the hospital; three died from measles complications.

Healthcare Professionals: Still the Front Line

Worried by stubbornly low vaccination rates and recent measles, pertussis and other disease outbreaks, lawmakers in several states are sponsoring bills to do away with “personal belief” exemptions that allow parents to opt out of the vaccination requirement for their children to attend school.14 Much as their predecessors did a century ago, they find themselves skirmishing every step of the way with anti-vaccination advocates.While 30 states already have laws banning personal exemptions, all but five states continue to allow religious exemptions.15

It is uncertain how this unending tension between the broad ideal of personal freedom and government use of mandates to protect everyone’s health will play out in the future. What is certain is that each day the sun comes up, a new crop of worried parents will raise questions or flatly refuse to allow vaccinations for their children. And each day, responsible, caring healthcare professionals will listen and acknowledge the fear, consider what they know about that parent’s background and thinking style, and patiently start a conversation that could, for better or ill, forever change the life of a young child.

*Following a 1989-1991 measles outbreak in the U.S. that infected 55,000 persons, mainly poor and uninsured children.

References

- Colgrove J. Science in a democracy: the contested status of vaccination in the progressive era and the 1920s. Isis 2005;96:167-191.

- World Health Organization. Smallpox and Its Eradication. Chapter 8: The Incidence and Control of Smallpox Between 1900 and 1958. Accessed at whqlibdoc.who.int/smallpox/9241561106_chp8.pdf.

- Mercola.com. Vaccines and Neurological Damage. Accessed at www.mercola.com/article/vaccines/neurological_damage.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Talking with Parents about Vaccines for Infants. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/conversations.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines and Immunizations: Basics and Common Questions. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/default.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Information Statements. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. If You Choose Not to Vaccinate Your Child, Understand the Risks and Responsibilities. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patiented/conversations/downloads/not-vacc-risks-color-office.pdf.

- Fine P, Eames K and Heymann DL. “Herd immunity”: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(7):911-16.

- Jain A, Marshall J, Buikema A, et al. Autism occurrence by MMR vaccine status among US children with older siblings with and without autism. JAMA 2015 Apr 21;313(15):1534-40.

- Taylor LE, Swerdfeger AL, Eslick GD. Vaccines are not associated with autism: an evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Vaccine 2014 Jun 17;32(29):3623-9.

- Detels R, Beaglehole R, Lansang MA, et al (eds.). Oxford Textbook of Public Health (Fifth Edition), 2011.

- Measles Outbreak — California, December 2014 — February 2015. MMWR 2015 Feb 20;64(06):153-54.

- Deer B. Secrets of the MMR scare. The Lancet’s two days to bury bad news. BMJ 2011 Jan 18;342.

- McGreevy P. Vaccination bill clears first legislative hurdle. Los Angeles Times, April 9, 2015, p. B4.

- Immunization Action Coalition. Exemptions Permitted for State Immunization Requirements. Accessed at www.immunize.org/laws/exemptions.asp.

- Vaccines.gov. Community Immunity (“Herd Immunity”). Accessed at www.vaccines.gov/basics/protection.