Healthcare Data: Ensuring Regulatory Compliance

Updated HIPAA rules require healthcare organizations stay vigilant in keeping patient data safe from threats in this ever-changing digital age.

- By Amy Scanlin, MS

ENSURING THE PRIVACY of patient health information is a required responsibility of healthcare providers under the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Signed into law in 1996, HIPAA continues to be updated and enhanced as new technology and privacy concerns lead to amended requirements about how data are protected. Some examples include requirements for how patient data are stored electronically and how health data are transported from portable devices to electronic health records (EHRs). Under HIPAA, providers are required to be compliant with the privacy rule, security and enforcement rule, and the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act that was part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Briefly, the privacy rule protects identifiable health information, regulates circumstances under which protected health information may be disclosed and requires specific arrangements for business associates (such as health information organizations and e-prescription gateways) that provide services to covered entities.

The security rule builds on provisions of the privacy rule by requiring security risk assessments and appropriate safeguards for electronic data handling. Every healthcare setting must perform risk assessments and document its physical, administrative and technical safeguards. Because safeguards differ for entity types, the rule allows for flexibility and scalability in terms of what an organization needs to do to accomplish its tasks. The security rule applies to health plans, healthcare clearinghouses and any healthcare provider who transmits health information in electronic form in connection with a transaction for which the Secretary of Health and Human Services has adopted standards under HIPAA (the covered entities) and their business associates.

The HITECH rule further strengthens the privacy and security rule, including requiring subcontractors of business associates to have a comparable level of security. Subcontractors are deemed those that create, receive, maintain or transmit personal health information on behalf of business associates. Tougher penalties for data breaches are also authorized, particularly in cases of willful neglect.1

Today’s Challenges

Balancing the need for privacy and security in an era of email and text communications, cloud storage and virtual appointments is one of today’s newest challenges. According to M3 Technology Consultants in Centreville, Va., medical data are worth 10 times more than credit cards on the black market, and website malware that holds data hostage and seeks out password and privacy information accounts for 69 percent of all data breaches. Notably, these security vulnerabilities affect both personal and professional systems, whether they are digital operating systems, cloud storage or even old-fashioned paper storage systems. And, the more sensitive the information, the more at risk it may be.

Regrettably, no matter how robust security is, people are its weakest link. Staff members who neglect to install critical software updates, misplace mobile devices, create weak passwords that can be easily deciphered, or feel they have been unfairly terminated all present grave concerns. “In nearly every case, the people are a company’s weakest link,” says Joseph P. Migliozzi, PE, MCSE, CCNA, RHCSA, president of M3 Technology Consultants. “From dormant accounts of persons who have left [practices], to simple, repetitive passwords, these are the most obvious vulnerabilities. The big stuff is rare, though it gets a lot of press. But, when someone out on the Internet finds a connection to a server, then successfully guesses the administrator password or finds an employee name on the Internet and starts trying to guess their password (their wife’s name or kid’s name, etc.), once they are in, they can see whatever they want. Those big software exploits that you hear about are much harder to do.”

And, these vulnerabilities create a number of considerations, including unique challenges that must be identified through assessments and managed via security plans, as well as responsibilities of providers and their business associates when a breach has been detected.

Understanding Risks

Federal law requires a risk assessment consistent with the HIPAA security rule to determine how electronic personal health information (ePHI) is protected within a system. This risk assessment should cover the most obvious points from who maintains keys to the physical building, to more in-depth questions such as who has access to what parts of a patient’s digital records. “It all comes down to assessing risk,” explains Lee Kim, BS, JD, CISSP, CIPP/US, director of privacy and security at Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, North America (HIMSS). “What are the critical or high-priority items to address? There is no such thing as 100 percent security, but if you address the high-impact items, you will go a long way.”

A good starting point for assessing risk is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ free 156-question Security Risk Assessment Tool2 available online, as well as a five-step tiered assessment of the risks of using mobile phones as a means of patient communication3 and a seven-step approach for implementing a security management process.4 Detailed information directed to both patients and providers about obtaining consent for exchanging health information electronically is also available.5

A more robust security assessment by a qualified expert familiar with healthcare settings will provide more information regarding specific ePHI risks and greater analysis than can be gained through an in-house assessment. It’s important to look at the size and complexity of an organization, its hardware and software security capabilities to determine the probability of ePHI risk at each level of data transmission while balancing the cost associated with the security measures. Kim recommends asking the following questions:

- Is this nascent technology reliable; have the “bugs” been worked out?

- What is the assessment of the risk as a result of adopting this new infrastructure for storage and transmission of data?

- What is the reputation of the manufacturer of the technology? Does it have a good track record for security?

- Where will the infrastructure be located? On premises? In the cloud? In the United States? Another country? (Each country/region has different data protection laws.)

- Will a third party the business associates with adopt and implement the same security policies and procedures? If not, why not, and what system does it have in place? Is it willing to provide information about its policies, procedures and design/architectural information?

- Who owns the third party? In which country is the third party located?

- If the third party will manage, control or have access to the organization’s data, how will it report any incidents that may occur involving the organization’s data?

- What is the reliability and availability of the remotely hosted resources?

Migliozzi suggests asking: “How is access to the network monitored and controlled? What can people see and not see on the network? How are devices controlled, tracked and monitored? What type of firewall security is there — from anti-spam to malware — and what tools are being used? What is the company’s exposure on the Internet, and how is intrusion protection monitored?”

With the ever-changing nature of data and data transmission, documented policies should be thoroughly implemented, and any changes to the types of data, hardware, software or policies that affect security should be documented as well. And, according to federal requirements, these records must be kept for six years, although states may have even lengthier requirements.

“Being able to balance data security and the potential security implementation costs is one important goal in conducting a risk analysis, and is a requirement of the HIPAA security rule,” says the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). “It is important to evaluate the likelihood and impact of potential risks to ePHI, then implement security measures to address those identified risks and document the chosen security measures and, where required, the rationale for their adoption. The security measures must address the administrative, physical and technical safeguards included within the HIPAA security rule.”

However and by whomever the risk assessment is undertaken, the ultimate success, outcome and responsibility for the results rest on the covered entity that is responsible for protecting the patient’s information. Before and during the process of evaluating EHRs, software and IT providers must discuss HIPAA rules and how the company intends to use the software with developers, says Migliozzi. They also need to verify that the IT company under consideration has a proven track record of working with the software under consideration or in use.

Security as a Culture

Security must be part of an organization’s culture. It must have an appointed security officer who receives appropriate training, including a thorough understanding of HIPAA compliance and oversight of risk assessment. The officer must document any security issues, and risks must be mitigated using the meaningful use security-related objectives set forth in the HIPAA security rule.4

All threats won’t necessarily be cyber in nature. Other potential risks include theft, workforce errors, disgruntled employees and even natural disasters such as fires, floods and earthquakes. The security officer must identify all risks and the likelihood of each to exploit vulnerabilities that would affect confidentiality, integrity and availability of ePHI.4

According to Kim, security must be accessible: “If employees and other workforce members cannot do their jobs, they will likely ‘work around’ policies, procedures and other restrictions that help keep the environment safe and secure. In other words, you cannot have such a restrictive and user-unfriendly security program that your workforce members are always trying to defeat it. In such a case, your program will either fail completely or have significant problems.” She suggests making sure policies are user-friendly and easy to understand, and she emphasizes companies need to teach employees why rules are in place. For instance, she says, “maybe even demonstrate what happens if a password is ‘shared’ with others or if the password is just ‘123456’ …, or if that strange PDF is opened up … what can happen to a computer, etc.? Get everyone involved and educated. Security is everyone’s responsibility.”

Everyone from staff to volunteers should be provided a copy of the security training manuals, and everyone should be involved in the conversation, not just those in charge of security. The organization should foster open communication and an opportunity for questions, and it should be open to suggestions for improvements from frontline staff who live the security operations daily.

Patients can also be involved in the protection of their information so they understand the seriousness and procedures in place to protect it. Invite them to ask questions, and help them understand how they can actively participate. “Patient education is an incredibly important part of meaningful consent,” says Peter Ashkenaz, an ONC spokesperson.

Sharing Information

Under the HIPAA privacy rule, covered entities can use protected health information and disclose it to another covered entity or their business associates for certain healthcare operations and under certain circumstances without seeking patient consent or authorization, according to Ashkenaz. Those circumstances include when both entities have or have had a relationship with the patient. However, the PHI requested must pertain to that relationship, and only a minimum amount of information may be disclosed that pertains only to the healthcare operation at hand. Some examples of when information can be shared include:6

- Conducting quality assessment and improvement activities;

- Conducting patient safety activities;

- Conducting population-based activities related to improving health or reducing healthcare costs;

- Conducting case management and care coordination;

- Contacting healthcare providers and patients with information about treatment alternatives; and

- Supporting fraud and abuse detection and compliance programs.

Communicating on Personal Devices

The ways in which people communicate are changing rapidly. From emails to texts between patients and providers to communication among providers via electronic health information exchanges, the opportunities for connections are advancing rapidly, as are the challenges of deciding how those communications will be conducted and maintained.

First, informed consent is an important aspect of these types of communications. Providers must do everything possible to ensure patients understand the various risks, from unsecured Wi-Fi connections to the vulnerabilities inherent to lost or stolen devices and unintended recipients of electronic communications. And, risks vary as do their potential severity.

While it is advised that providers get written consent from patients prior to engaging in electronic communications, under HIPAA guidelines, patients who initiate text conversations may be providing consent to communicate electronically.7 Even so, extra care and concern should be taken to ensure certain patients understand the risks, and providers must ensure they are meeting federal requirements. The security and encryption of electronic data should never be taken for granted, no matter how robust the system.

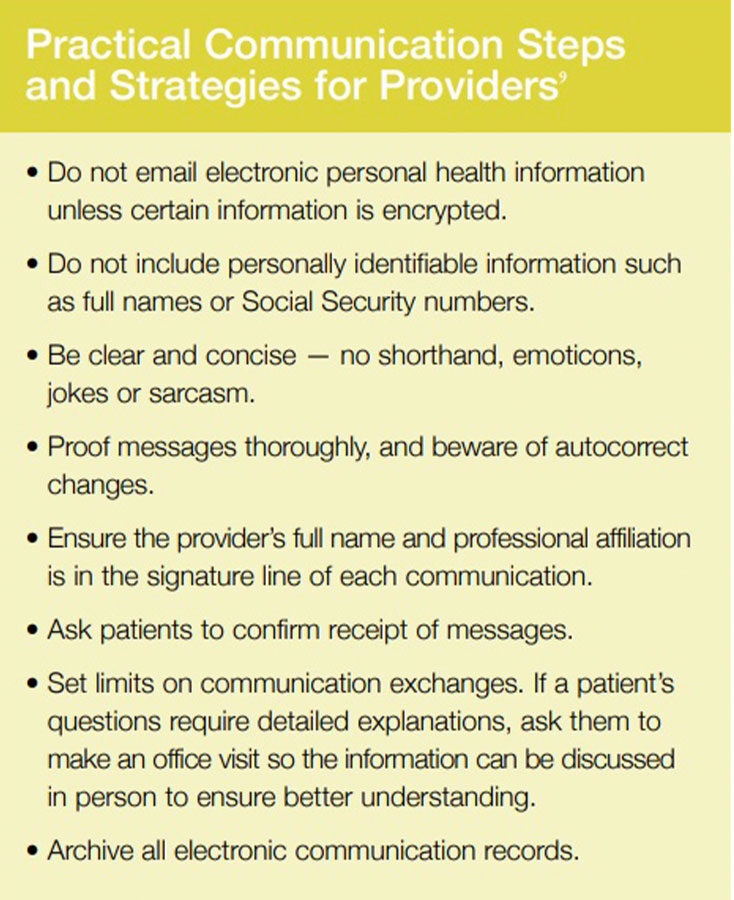

Online communications, whether between providers and patients or between providers discussing patients’ charts (including emails, texts and communications via patient portals), must meet the security rule and meaningful-use standards for secure messaging of ePHI, and they must be encrypted.

The question of whether to allow providers to access ePHI via their personal mobile devices is sometimes raised to balance busy work schedules. The answer, says Migliozzi, is “no; having separate phones is better.” While professionally managed security is generally updated automatically, the same may not be true for personal systems, which increase security risks. However, M3 Technology Consultants suggests that if a bring-your-own-device policy is allowed, organizations must tightly manage security and follow HIPAA compliance.

Another concern, says Migliozzi, is privilege misuse, which accounts for 5 percent of breaches. “Most often, this translates to current or former employees or contractors intentionally misusing administrative privileges for the purpose of harming the company,” he says. So, he suggests granting access on a need-to-know basis to as few individuals as possible and creating and enforcing policies restricting access to sensitive data. He also suggests expediting the change of all usernames and passwords for accounts after employee terminations.

Notification of Data Breach

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Information Privacy for Professionals, unless otherwise requested by law enforcement, covered entities must notify affected individuals of a data breach as soon as is reasonably possible and no later than 60 days after the breach was first discovered or should have been discovered. Also, if covered entities have insufficient or out-of-date contact information for 10 or more individuals, they must provide substitute individual notice by either posting the notice on the homepage of its website for at least 90 days or by providing the notice in major print or broadcast media where the affected individuals likely reside.7 However, covered entities generally have only a 30-day window to make corrective actions to modify a situation of willful neglect that allowed the breach to occur.1

“Breach notification requirements differ according to the jurisdiction,” says Kim. “We have to be concerned not just with federal laws and regulations, but also local and state laws and regulations as well. These laws and regulations dictate who needs to be notified and when. As with any incident, you need to contain the incident. That’s the way you can reduce or mitigate the outflow of information. Obviously, the incident must be contained quickly. The more quickly it can be contained, the better off one will be. We also need to create an environment which fosters information sharing [so that] people [aren’t] afraid of [automatically] losing their jobs if an incident occurs (actual or suspected). Breaches can get very large in volume if people are hesitant to report … the problem just compounds.”

Preparing for the Unexpected

Security requirements for healthcare organizations can be very confusing. What should be protected, how it should be protected and the best path forward are best described as a multitiered flow chart with many moving parts.

Organizations should keep security risk analysis reports, signed business associate agreements, EHR logs that demonstrate use of security features and safeguards, and notated efforts to monitor user actions. Importantly, they should also keep incident and breach information and make sure staff understands it is the policy to randomly monitor computer habits.

Hope is not a plan. The best way to protect against cyber incidents is to prepare for the unexpected. There are many resources available. The ONC and Office of Civil Rights have vast amounts of user-friendly information and guidance available online.8 Organizations such as HIMSS can help promote understanding about sound policy and information practices. And, IT security companies such as M3 Technology Consultants can help provide workable solutions for safer online environments.

Ultimately, the responsibility of cyber security and following meaningful use falls on organizations, no matter where missteps may have occurred.

References

- American Health Information Management Association. Analysis of Modifications to the HIPAA Privacy, Security, Enforcement, and Breach Notification Rules Under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act and the GeneticInformation Nondiscrimination Act; Other Modifications to the HIPAA Rules, Jan. 25, 2013. Accessed at library.ahima.org/PdfView?oid=106127.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Security Risk Assessment Tool. Accessed at www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/security-risk-assessment-tool.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mobile Device Privacy and Security: Five Steps Organizations Can Take to Manage Mobile Devices Used by Health Care Providers and Professionals. Accessed at www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/five-steps-organizations-can-take-manage-mobiledevices-used-health-care-pro.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Guide to Privacy and Security of Electronic Health Information, Chapter 6: Sample Seven Step Approach for Implementing a Security Management Process. Accessed at www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/privacy/privacy-and-security-guide-chapter-6.pdf.

- U.S.Department of Health and Human Services. Patient Consent for Electronic Health Information Exchange. Accessed at www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/patient-consent-electronic-health-information-exchange.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Covered Entities and Business Associates. Accessed at www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/covered-entities/index.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Breach Notification Rule. Accessed at www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/breach-notification.

- Miller, RN. When Patients Want to Text: HIPAA, OMG! See You L8R, Privacy? AMA Wire, April 17, 2017. Accessed at www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/hipaa/when-patients-want-text-hipaa-omg-see-you-l8r-privacy.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Cyber Security Guidance Material. Accessed at www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/security/guidance/cybersecurity/index.html.