HPV Vaccine: A Dose of Untapped Potential

It is estimated that 79 million Americans are currently infected with human papillomavirus (HPV), and an additional 14 million HPV infections occur each year. The disease is so common, nearly everyone will be infected at some point. Approximately 26,000 new cancers each year are HPV-related, and most could be prevented with a simple three-dose series of HPV vaccine. While other countries are moving forward with successful HPV vaccination initiatives and seeing significant declines in infection in their populations, U.S. vaccination rates remain stagnantly low. With more than 4,000 preventable1 deaths a year in the U.S., why aren’t Americans getting vaccinated?

- By Hillary Johnson, MHS

It is estimated that 79 million Americans are currently infected with human papillomavirus (HPV), and an additional 14 million HPV infections occur each year. The disease is so common, nearly everyone will be infected at some point. Approximately 26,000 new cancers each year are HPV-related, and most could be prevented with a simple three-dose series of HPV vaccine. While other countries are moving forward with successful HPV vaccination initiatives and seeing significant declines in infection in their populations, U.S. vaccination rates remain stagnantly low. With more than 4,000 preventable1 deaths a year in the U.S., why aren’t Americans getting vaccinated?

On July 23, 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released data from the 2013 National Immunization Survey of Teens (NIS-Teen), a very large, nationally representative survey that collects clinician-validated vaccination histories of adolescents ages 13 years to 17 years. The 2013 report summarized information on 18,264 teens and found that only 57.3 percent of girls and 34.6 percent of boys had initiated the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ (ACIP) recommended three-dose HPV vaccination series. And while vaccination coverage with greater than or equal to one dose of HPV vaccine had increased from 2012 (from 53.8 percent in 2012 to 57.3 percent in 2013 among adolescent girls and from 20.8 percent in 2012 to 34.6 percent in 2013 among adolescent boys), 2011 to 2012 had shown no improvements among adolescent girls at all.2

Admittedly, HPV vaccine is a relative newcomer to the list of ACIP routine recommendations (Merck’s Gardasil was approved in 2006), and incremental entry into the market would be expected with any new vaccine. However, while CDC describes the initial uptake of HPV vaccine as good, it plateaued much sooner than expected. “We often think of about a 10 percentage point increase per year the first few years after a vaccine is recommended,” says Dr. Anne Schuchat, assistant surgeon general in the U.S. Public Health Service and the director of CDC’s National Center of Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. “So it was an early plateau.”3

There are three routine vaccines targeted at adolescents, and ACIP also recommends administration of these and all age-appropriate vaccines during a single visit (typically the well-child visit at 11 or 12 years of age). These include the HPV vaccine, the Tdap vaccine that protects against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (whooping cough), and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY). With vaccine acceptance for HPV so low, but 2013 coverage estimates for Tdap and MenACWY at 86.0 percent and 77.8 percent, respectively,4 there is clearly a disconnect among consumers and what should be considered three simultaneously recommended and administered vaccines.

A Cancer-Causing Virus

Human papillomavirus, or HPV, encompasses a group of more than 150 related viruses, each referred to as a “type” and given a number to distinguish it. Originally named for the warts (or papillomas) some HPV types cause, it was Dr. Harold zur Hausen’s Nobel Prize-winning research in the 1970s that pursued the idea that HPV played a role in cervical cancer as well. We now know that approximately 40 HPV types affect the mucosal or genital regions of the body, with some types classified as high-risk and cancer-causing (most notably HPV 16 and 18 — responsible for 70 percent of cervical cancers) and some types classified as non-cancer-causing and low-risk (most notably HPV 6 and 11 — accounting for 90 percent of anal and genital warts).

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI), and nearly all men and women will become infected with at least one type of HPV at some point in their lives.5 Transmission occurs from skin-to-skin contact, and people do not need to be symptomatic to spread the virus. CDC estimates more than 79 million Americans are currently infected, and 14 million new infections occur each year domestically.6 Most often, people remain asymptomatic and will never even know they had the virus, but for those who do manifest disease, the results can be devastating.

HPV is associated with cervical, vulvar and vaginal cancers in females, penile cancer in males, and anal and oropharyngeal cancer in both males and females. HPV types 16 and 18 cause the majority (64 percent) of all HPV-associated cancers (approximately 21,300 cases annually).7 Worldwide, 500,000 women are diagnosed each year with cervical cancer alone, and 250,000 will die of their disease.8

A Cancer-Preventing Vaccine Emerges

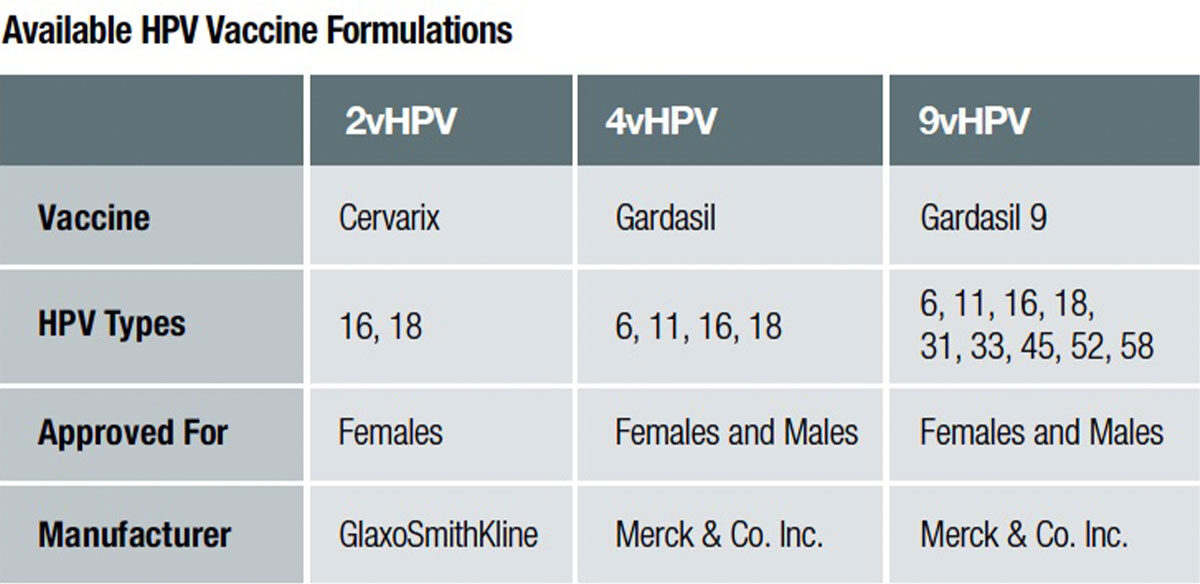

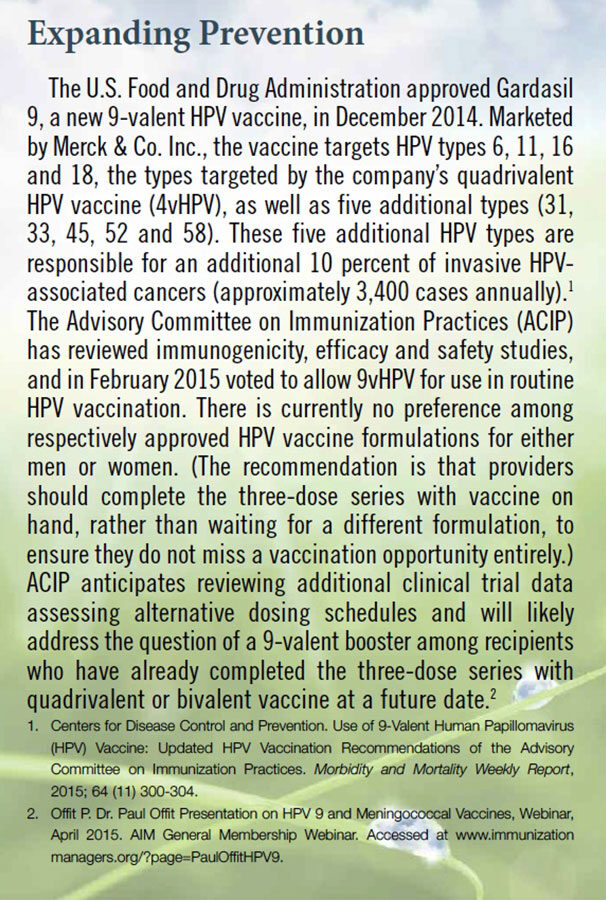

Two companies currently have approved HPV vaccines licensed for use in the U.S.: bivalent HPV vaccine (2vHPV) called Cervarix by GlaxoSmithKline, and quadrivalent (4vHPV) and 9-valent (9vHPV) HPV vaccines by Merck & Co. called Gardasil and Gardasil 9, respectively. HPV vaccines utilize recombinant DNA technology (meaning DNA from different species are combined together). A host plasmid is injected with a surface protein gene (L1) from HPV DNA to generate viral proteins capable of self-assembling into virus-like particles (VLPs) for each of the targeted HPV types. The HPV VLPs look superficially identical to actual HPV under the microscope, but they do not have a genome within so cannot reproduce themselves. Encountering the L1 HPV surface protein effectively mimics exposure to HPV and provokes the immune system to generate antibodies against specific types of HPV targeted in the vaccine. As a result, HPV vaccines are some of the most immunogenic vaccines available, and produce better immune response in the body than natural infection.1

HPV vaccine is a prophylactic, or preventive, vaccine, meaning it works best before exposure.

And, What’s More, the HPV Vaccine Works

Some of the best data available on vaccine efficacy comes from Australia, where in 2007, the country began implementing a nationwide school-based 4vHPV vaccination campaign. By 2010, Australia had achieved more than 80 percent coverage for the first two doses of HPV vaccine among 12- to 13-year-old girls. The nation saw large declines (92.6 percent) in the proportion of women under 21 years of age diagnosed with genital warts during the vaccination period, consistent with vaccine-induced protection.9 (As genital warts occur much sooner after HPV infection [on average weeks to months, as opposed to several years after infection for cancer to appear],10 these data serve as an early indicator of potential vaccine efficacy.) Additionally promising, in 2011, no genital wart diagnoses were made among 235 women under 21 years of age who reported prior HPV vaccination. While Australia targeted only girls for vaccination in the program, researchers still noted an 81 percent decline in the proportion of men under 21 years diagnosed with genital warts during the vaccination period as well, indicating notable herd immunity at the high coverage level. No significant decline in genital wart diagnoses were seen in men and women over 30 years of age (a group not targeted for vaccination) during the study period.9

Australia is not alone. Published reports of declines in HPV vaccine type prevalence and anogenital warts from several other countries (including Denmark,11 Germany12 and New Zealand13) further strengthen the evidence of direct, as well as indirect, impact of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine.

U.S. Success

The U.S. has not achieved anywhere near the vaccine coverage demonstrated in the Australian study, but early data still shows an impact in disease prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) data showed a 56 percent decline in prevalence of HPV 6/11/16/18 across surveyed pre- and post-vaccine era girls ages 14 years to 19 years. NHANES is conducted every two years and is considered the gold standard on health indicators. For the survey, government health workers interviewed more than 8,000 girls and women ages 14 years to 59 years and collected vaginal swabs that were evaluated by CDC. Prior to the availability of HPV vaccination, HPV infection rates were steady among all age groups of women. The subsequent declines noted in younger, vaccinated age groups were not observed in older, unvaccinated age groups, further highlighting the vaccine’s impact.14

Another early indicator of success can be seen in a recent study examining incidence of genital warts among U.S. service members. Researchers found that incidence rates of genital warts diagnoses markedly declined among female service members in the 4vHPV vaccine-eligible age range from 2007 (following introduction of the 4vHPV vaccine) through 2010.15

Too Young for STI Protection? A Taboo Topic for Parents

Many parents think HPV vaccine is not needed, or rather, not needed “yet” when it comes to STI prevention. It is a costly assumption on many levels. The research on HPV antibody data shows that adolescents at the 11- and 12-year-old age range have much higher antibody response than do older teens or young adults.16 This is also the ideal age for vaccination exactly because very little exposure to HPV occurs among young adolescents, and the vaccine works best prior to exposure when both boys and girls, fully vaccinated with the three-dose series, have had the time to develop the antibody protection. And while the research will continue to follow vaccinated adolescents into adulthood, there has been no evidence of waning protection over time.16,17

The notion of sexual activity among youth brings with it a potential rabbit hole of questions among HPV vaccine-hesitant parents. Some believe that their children are not yet at risk for STIs (and thus do not need the HPV vaccine), and some critics have expressed concern that vaccination might encourage earlier onset of risk-taking behaviors. Research has addressed both these issues.

Unfortunately, a 2012 study in the Journal of Infectious Diseases found that HPV was detected in 46 percent of women “prior” to their first vaginal sex.18 This highlights the high transmissibility of HPV. Transmission can occur from intimate skin-to-skin contact, and intercourse is not required19 (again reinforcing the need to vaccinate at a younger age prior to exposure). Luckily, contrary to some parental worries, it seems HPV vaccination is not a blank check for unsafe sexual activity. Multiple studies have shown that HPV vaccination is not associated with increased sexual activity outcomes that include pregnancy, STI testing or diagnosis, or contraceptive counseling.20,21

Sexual activity can be a tricky topic among providers and parents of children at such a young age. However, providers often actually overestimate parents’ concerns. Missed opportunities can result from assumptions about the timing of vaccination relative to sexual activity as well.22 CDC advises routine recommendation of HPV vaccine as “cancer” prevention rather than “STI” prevention to address this issue.

But, Is the HPV Vaccine Safe?

The 2013 NIS-Teen asked parents who reported they were not likely to vaccinate their teen in the 12 months after interviews, or were unsure of their vaccination plans, to identify the main reason why their teen would remain unvaccinated. Safety ranked third for girls and fifth for boys.2 In the U.S., postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring and evaluation are conducted independently by federal agencies and vaccine manufacturers. Today, HPV is one of the best-studied vaccinations. Clinical trials studied bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines in a cumulative 60,000 people.23 Since licensure, more than 67 million doses have been distributed in the U.S., and more than one million people have been studied in postlicensure trials.24 No serious safety concerns have been linked to HPV vaccinations in any of these studies.2

The most common adverse events, or side effects, reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) are considered mild and include injection-site reactions (such as pain, redness or swelling), dizziness, fainting, nausea and headache. Although considered mild, these reactions should be and are taken seriously, particularly the risk of syncope, or fainting. As a result, ACIP updated its vaccination recommendation to include information about preventing falls and possible injuries from fainting after receiving shots. Providers should share this information with their patients and have the patients remain seated and observed for 15 minutes after receiving a shot. It is also noted that HPV vaccine is one of the most painful vaccines because of its high salt concentration.

Overall, reports of adverse events to VAERS have been decreasing each year since 20082 and are consistent with prelicensure clinical trial data and with the 2009 published summary of the first 2.5 years of postlicensure reporting to VAERS.2 Among serious adverse events reported, no unusual patterns or clustering has been identified that would suggest events were caused by HPV vaccine.23 And while recent comments by celebrities have helped perpetuate the safety question in the news (see The Celebrity Touch), national safety monitoring data continue to indicate that the HPV vaccine is safe.2

While Rates of Vaccine Uptake Among Girls May Seem Low, Boys Have Even Further to Go

A routine recommendation of HPV vaccine for females was first published in June 2006. Recommendations for males have taken a slightly more complicated journey. ACIP first published a permissive “may be given” recommendation for 4vHPV for males in October 2009, and did not publish a full routine recommendation for boys until October 2011. Dr. Paul Offit of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia argues that this delayed recommendation for 4vHPV for boys may have led to a false public perception among some that HPV was not as important for boys. “We certainly knew even by 2006 that the [4vHPV] vaccine could prevent [HPV] infection in men,” he said in a recent Association of Immunization Managers presentation. “I think what they were waiting for was data showing that it could prevent anal cancers in men, and those data came later. But you know, obviously, if a vaccine can prevent infection, it can prevent cancer. A cell can’t be transformed to become cancerous if it can’t be infected.”1

About one-third of HPV-associated cancers occur in males. While cervical cancer does occur most frequently, the second most diagnosed HPV-associated cancer is oropharyngeal, almost 80 percent of which are in males.24 HPV vaccine benefits both males and females.

Making Use of the Tools at Hand

The data show that a recommendation from a healthcare professional is strongly associated with teens getting vaccinated. While the percentage of parents who reported receiving a recommendation for HPV vaccine increased in 2013 NISTeen, nearly one-third of parents of girls and more than half of parents of boys reported that their child’s clinician had not recommended HPV vaccine for their child.2 One of the top five reasons parents listed for not getting the HPV vaccine for their child was that it had not been recommended to them by their teen’s doctor or nurse. Other studies show similar results. A 2014 study published in Pediatrics listed a lack of a physician recommendation as the most common reason (44 percent) parents reported for not vaccinating their daughters.22

The keys to moving forward and reducing vaccine-preventable infections and cancers caused by HPV lie in improving practice patterns and ensuring clinicians utilize every opportunity to recommend HPV vaccines and address parent questions and concerns, particularly around safety and need.

At 12,000 cases of cervical cancer and 4,000 deaths a year in the U.S., CDC estimates that maintaining current HPV vaccination levels would prevent 45,000 cases of cervical cancer and 14,000 deaths among a cohort of girls now age 13 and younger over the course of their lifetimes. However, increasing vaccination levels to 80 percent (on par with other recommended adolescent vaccines) would prevent an additional 53,000 cancers and nearly 17,000 deaths.25

And there are plenty of chances to do so. When a teen is in the doctor’s office and receives another vaccine, but not HPV, that is a missed opportunity. CDC estimates that if every time an 11- or 12-year-old girl received another vaccine and HPV was administered as well, HPV coverage by the 13th birthday would have been 91 percent for girls.2

Providers have indicated they need resources to speak to their patients’ parents, and CDC has produced a website full of resources in response: cdc.gov/vaccines/YouAreTheKey.

Unlike many other diseases addressed through vaccination, severe sequelae from HPV often do not appear until years or decades after exposure. This means that the pediatricians responsible for recommending and administering the HPV vaccine are not likely to be the diagnosing provider when HPV manifests into a disease like cancer. That is why it is important to take advantage of every opportunity available to educate both patients and providers on the importance of HPV vaccination. Clinicians should strongly recommend the HPV vaccine the same way and the same day they recommend and administer meningococcal conjugate and Tdap vaccines.

References

- Offit P. Dr. Paul Offit Presentation on HPV 9 and Meningococcal Vaccines, Webinar, April 2015. AIM General Membership Webinar. Accessed at www.immunizationmanagers.org/?page=PaulOffitHPV9.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents, 2007–2013, and Postlicensure Vaccine Safety Monitoring, 2006–2014 — United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2014; 63 (29) 620-624.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, July 23). CDC Telebriefing on National Immunization Survey — Teen Results and HPV Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents. Transcript accessed at www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/t0724-hpv-vaccination.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2014; 63 (29) 625-633.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Is HPV? Accessed at www.cdc.gov/hpv/whatishpv.html.

- Schuchat A and Roark JB (2014, January 28). HPV Vaccine Is Cancer Prevention… So What’s the Hold Up? [Webinar]. VIC Network Webinar Series. Accessed at www.vicnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/VICNetwork-Webinar-HPV-01-28-14.mp4.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine: Updated HPV Vaccination Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2015; 64 (11) 300-304.

- HPV Vaccination: Predicting Its Effect on Cervical Cancer Rates. PLoS Medicine, 2006;3(5):e202. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030202. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1434510.

- Ali D, et al. Genital Warts in Young Australians Five Years Into National Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Programme: National Surveillance Data. British Medical Journal, 2013;346:f2032. Accessed at www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f2032.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (March 2013). STD Curriculum for Clinical Educators. Genital Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Module. Accessed at www2a.cdc.gov/stdtraining/ready-to-use/hpv.htm.

- Baandrup L, Bloomberg M, Dehlendorff C, et al. Significant Decrease in the Incidence of Genital Warts in Young Danish Women After Implementation of a National Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Program. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2013 Feb;40(2):130-5. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31827bd66b. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23324976.

- Mikolajczyk RT, Kraut AA, Horn J, et al. Changes in Incidence of Anogenital Warts Diagnoses After the Introduction of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Germany — An Ecologic Study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2013 Jan;40(1):28-31. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182756efd. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23250300.

- Oliphant J and Perkins N. Impact of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine on Genital Wart Diagnoses at Auckland Sexual Health Services. New Zealand Medical Journal, 2011 Jul 29;124(1339):51-8. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21952330.

- Markowitz LE, Hariri S, Lin C, et al. Reduction in Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Prevalence Among Young Women Following HPV Vaccine Introduction in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2003–2010. Journal of Infectious Diseases, (2013) doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit192. Accessed at jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2013/06/18/infdis.jit192.abstract.

- Nsouli-Maktabi H, Ludwig SL, Yerubandi UD, and Gaydos JC. Incidence of Genital Warts Among U.S. Service Members Before and After the Introduction of the Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report, 2013 Feb;20(2):17-20. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23461306.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2007; 56(RR02);1-24. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5602a1.htm.

- Nauda PS, Roteli-Martins CM, De Carvalho NS, et al. Sustained Efficacy, Immunogenicity, and Safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-Adjuvanted Vaccine. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics, 2014 June; 10 (8): 2147-2162. doi:10.4161/hv.29532. Accessed at www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.4161/hv.29532#.VTUmjdzF_4s.

- Shew ML, Weaver B, Tu W, et al. Frequent Detection of Vaginal Human Papillomavirus Prior to First Sexual Intercourse During Longitudinal Observation. Journal of Infectious Diseases, (2013) 207 (6): 1012-1015. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis775. Accessed at jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/207/6/1012.

- World Health Organization. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Cervical Cancer. Accessed at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs380/en.

- Bednarczyk RA, Davis R, Ault K, Orenstein W, and Omer SB. Sexual Activity-Related Outcomes After Human Papillomavirus Vaccination of 11- to 12-Year-Olds. Pediatrics, 2012; 130:798–805. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23071201.

- Jena AB, Goldman DP, and Seabury SA. Incidence of Sexually Transmitted Infections After Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among Adolescent Females. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2015;175(4):617-623. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7886. Accessed at archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2109856.

- Perkins RB, Clark JA, Apte G, et al. Missed Opportunities for HPV Vaccination in Adolescent Girls: A Qualitative Study. Pediatrics, 2014: doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0442. Accessed at pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2014/08/12/peds.2014-0442.full.pdf+html.

- North Dakota Cancer Coalition. HPV (Human Papillomavirus) Vaccination — Myths and Misconceptions. Accessed at www2a.cdc.gov/cic/documents/external/pdfAll%20Attachments.pdf.

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Vaccine Education Center. Vaccine Update Webinar Q & A, Mar. 18, 2015. Accessed at media.chop.edu/data/files/pdfs/webinar-qa-spring2015.pdf.

- Tavernise S. HPV Vaccine Is Credited in Fall of Teenagers’ Infection Rate, New York Times, June 19, 2013. Online. Accessed at www.nytimes.com/2013/06/20/health/study-findssharp-drop-in-hpv-infections-in-girls.html.