Replacement Therapy for Hereditary Angioedema: Innovations Define a New Standard of Care

- By Keith Berman, MPH, MBA

LIVING WITH HEREDITARY angioedema (HAE) is a painful, disabling and often frightening experience. This rare autosomal dominant disorder, characterized by a deficiency (type I) or a dysfunction (type II) of the C1 inhibitor protein, manifests as recurrent acute attacks of localized edema, usually affecting the skin or the respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts. While the frequency, severity and localization of these angioedema attacks varies widely from one individual to the next, at least 50 percent of patients experience a life-threatening laryngeal attack caused by asphyxiation due to upper airway obstruction.1

Historically, HAE treatment options were few and limited by dose-related toxicity. But the recent approvals of a number of effective new treatments have dramatically improved the prognosis for the roughly one in 50,000 people affected by this disorder (Figure 1).

The Roles of C1 Inhibitor

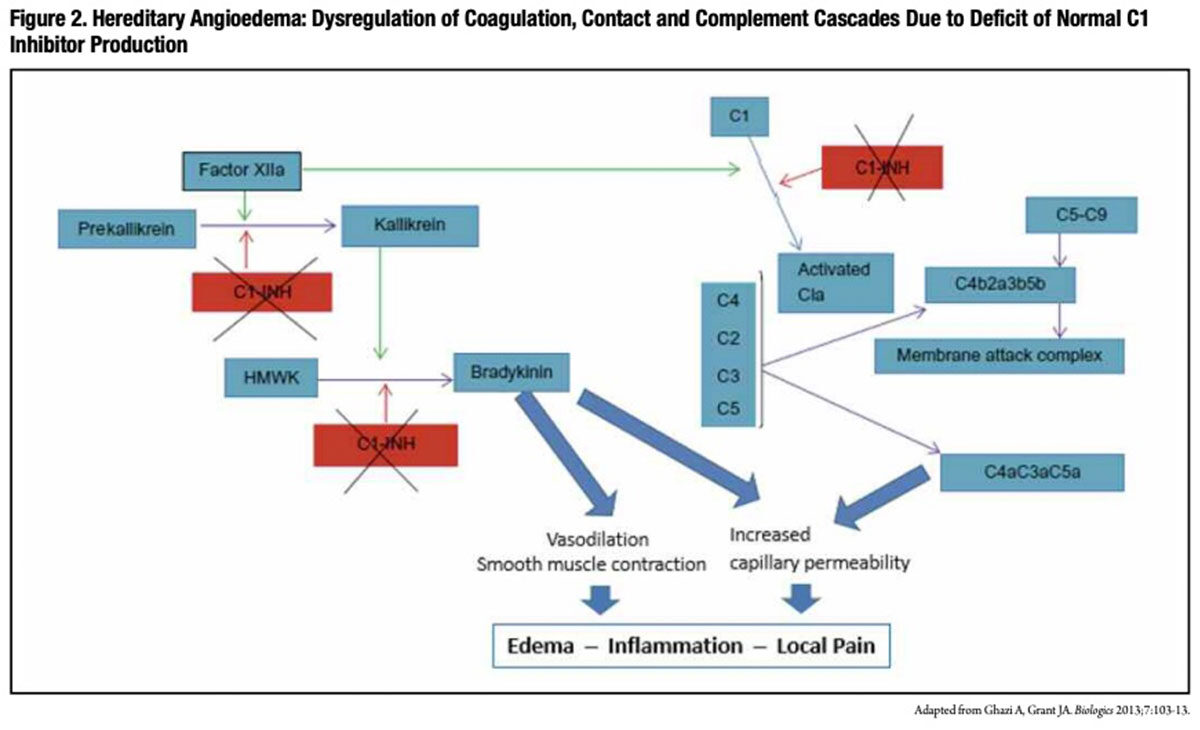

Also referred to as C1 esterase inhibitor, C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) is a key inhibitor of coagulation factors XIa and XIIa, complement component C1 and plasma kallikrein. Through multiple complex pathways, C1-INH modulates the extent of increased microvascular permeability and edema that normally occurs during an inflammatory reaction. In particular, C1-INH acts to regulate the conversion of prekallikrein to kallikrein, which in turn limits production of bradykinin, a powerful vasodilator thought to be responsible for the characteristic symptoms of localized swelling, inflammation and pain associated with HAE attacks.

Conversely, low functional C1-INH levels permit the unchecked generation of bradykinin, anaphylatoxins and chemotaxins that induce and perpetuate the vasodilation, smooth muscle contraction and increased capillary permeability (Figure 2) that are thought to account for painful swelling involving the extremities, gut tract, larynx and face (Figure 3) in persons with HAE. While angioedema attacks usually occur spontaneously with no clear causal factor, emotional stress, local tissue trauma, menstruation, infections and use of certain medications are all known to trigger attacks.

Historical HAE Management

Until recently, management of HAE was largely limited to long-term prophylactic treatment with attenuated androgens (e.g., danazol and stanozolol), which reduce the number and severity of angioedema attacks by boosting endogenous biosynthesis of C1-INH, or with antifibrinolytic drugs (e.g. epsilon aminocaproic acid), whose mechanism of action is unknown.

Unfortunately, chronic administration of therapeutic doses of attenuated androgens is frequently associated with hepatotoxicity, virilization and an array of other dose-related side effects that many patients cannot tolerate.2,3 Further, attenuated androgens are not useful in the acute treatment of angioedema attacks. Prophylaxis with antifibrinolytic agents has proven not to be reliably effective.4,5

In 1980, European and U.S. investigators published reports of the successful use of C1-INH concentrates purified from human plasma to treat acute episodes of angioedema in HAE patients.6,7 But while C1-INH was soon adopted as a standard therapy in Germany and elsewhere in Europe, it remained unavailable in the U.S. for the next three decades.

C1 Inhibitor Approved to Treat HAE Attacks

In 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved CSL Behring’s C1-INH concentrate, Berinert, for the treatment of acute abdominal or facial HAE attacks in adults and adolescents,* based on safety and efficacy findings from a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized prospective clinical study in 125 subjects.8 At least 70 percent of subjects in both the Berinert and placebo groups were suffering from abdominal attacks at baseline.

In subjects treated with 20 IU/kg body weight of Berinert for any acute attack, the median time to onset of symptom relief was significantly reduced compared to placebo treatment. The reduction in time to onset of relief was most pronounced in severe attacks: 0.5 hour versus 13.5 hours. In the subset of subjects experiencing abdominal attacks, the median time to start of relief of the last symptom (e.g., pain, nausea, vomiting, cramps and diarrhea) present at baseline to improve was one hour for Berinert group subjects, compared to 24 hours for placebo group subjects.1

In 2012, FDA approved a label expansion that allows for self-administration of Berinert with appropriate training, translating into an opportunity for much faster relief of symptoms. “Once the early signs of an HAE attack begin to emerge, any delay in starting treatment can increase the severity of that attack … and can lead to a patient needing to be hospitalized,” noted study investigator Bruce Zuraw, MD. “However, if a patient self-administers therapy as soon as symptoms begin to appear, these problems can usually be averted.”

Self-administration at the onset of an abdominal or facial HAE attack resulted in a median onset of relief of just 48 minutes, versus more than four hours for the placebo group. In an extension study, self-administration of Berinert to treat potentially life-threatening laryngeal attacks provided a median onset of relief of just 15 minutes; based on these findings, FDA also approved Berinert for laryngeal attacks in addition to facial and abdominal attacks.9

But in patients with underlying risk factors, such as presence of an indwelling catheter, prior history of thrombosis, underlying atherosclerosis and immobility, there have been reports of serious arterial and venous thromboembolic events following administration of Berinert and other C1-INH products. As such, physicians are advised to weigh the benefits of treatment of HAE attacks against the risks of thromboembolic events in patients with underlying risk factors.2

Short-Acting Peptides Approved to Treat HAE Attacks

In addition to the licensure of several C1-INH concentrates, FDA approved two other novel treatments for acute attacks in HAE patients from 2009 to 2011: KALBITOR (ecallantide) and FIRAZYR (icatibant). By different mechanisms of action, these agents respectively act to inhibit the production or the activity of bradykinin, the primary mediator of painful, edematous HAE attacks.

KALBITOR, a 60-amino-acid recombinant peptide produced in yeast cells, selectively inhibits plasma kallikrein. Through its direct interference with kallikrein, KALBITOR reduces swelling and inflammation by inhibiting the conversion of high molecular weight kininogen to bradykinin. A pair of randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trials evaluated the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous delivery of 30 mg of the product for treatment of acute HAE attacks in a total of 168 adult and adolescent patients. In both trials, KALBITOR significantly reduced attack severity from baseline to four hours posttreatment. Of 187 HAE patients treated with subcutaneous KALBITOR, five (3 percent) experienced anaphylaxis, usually within one hour of administration. As symptoms of potentially life-threatening anaphylaxis are similar to acute HAE symptoms, prescribers are cautioned to closely monitor patients for any signs of a serious allergic reaction. About 20 percent of patients seroconverted with anti-ecallantide antibodies, the rate increasing with exposure over time. Other common side effects included headache, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea and upper respiratory tract infection.10

FIRAZYR is a selective bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist, with a binding affinity similar to bradykinin. This synthetic short-acting decapeptide competitively inhibits bradykinin from binding the B2 receptor on target cells, interfering with its vasodilatory action that results in swelling, inflammation and pain. If the response is deemed inadequate or if symptoms recur after the initial 30 mg subcutaneous dose, up to two additional doses may be administered in a 24-hour period. In a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 98 adult patients with HAE who developed moderate to severe cutaneous or abdominal attacks, the median time to a 50 percent reduction in symptoms following FIRAZYR treatment was 2.0 hours (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5 to 3.0 hours) versus 19.8 hours (95% CI, 6.1 to 26.3 hours) following placebo treatment (P<0.001). Near-complete symptom relief was attained in a median of eight and 36 hours, respectively, for the two treatment groups.11

Unlike KALBITOR, which must be administered by a qualified healthcare professional due to a risk of anaphylaxis, FIRAZYR can be safely self-administered by properly trained patients upon recognition of symptoms of an HAE attack. The advantage of self-administration is plainly evident: It shortens delay to initiation of treatment, limiting the severity of acute attacks, including potentially life-threatening laryngeal attacks.

Intravenous C1 Inhibitor Prophylaxis for HAE

Optimal HAE management is treatment to prevent painful and disabling HAE attacks from occurring in the first place, or at least to reduce the number and severity of breakthrough attacks that occur. The most obvious solution for patients with severe disease is chronic replacement of absent or dysfunctional endogenous C1-INH with regular infusions of C1-INH concentrate.

Routine prophylaxis with a human C1-INH was finally evaluated a decade ago in a study of 22 subjects, who were randomly assigned to receive intravenous injections of saline placebo or 1,000 units of Shire’s CINRYZE C1-INH product every three to four days for 12 weeks. Patients were then crossed over to the alternative treatment for a second 12-week evaluation period.12

Mean attack rates for all 22 subjects during the two 12-week crossover periods were 6.26 and 12.73 for the C1-INH and placebo treatments, respectively. This difference of 6.47 attacks was highly significant (95% CI, 4.21 to 8.73; P<0.001). Further, the mean attack severity score (on a 3-point scale with 1 indicating mild, 2 moderate and 3 severe) was significantly lower with C1-INH prophylaxis than with placebo (1.3 ± 0.85 versus 1.9 ± 0.85; P<0.001). The total duration of attacks was likewise significantly shorter with C1-INH prophylaxis than with placebo (2.1 ± 1.13 versus 3.4 ± 1.39 days; P<0.002). Half as many subjects on C1-INH prophylaxis required open-label rescue therapy for HAE attacks as those receiving placebo. Common nonserious reactions with CINRYZE administration included headache, nausea, rash and vomiting.

Based on these and other findings, FDA approved CINRYZE in 2008 for routine prophylaxis against HAE attacks. With appropriate training, CINRYZE can now be self-administered by patients.

But as with Berinert administration, there is a risk of thromboembolic events with this intravenously infused product. In an open-label trial that further investigated prophylactic use of CINRYZE in 146 HAE patients, five serious thromboembolic events were reported (myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and two cerebrovascular accident events) — all in patients with underlying risk factors.13

Three years ago, a third C1-INH replacement therapy option became available when FDA approved Pharming’s novel recombinant human C1-INH product, brand named RUCONEST, for treatment of acute HAE attacks in adults and adolescents. Purified from the milk of transgenic rabbits, intravenous RUCONEST administration at 50 IU/kg results in accelerated and sustained relief of symptoms of HAE attacks, despite a much shorter elimination half-life than human plasma-derived C1-INH concentrates.14

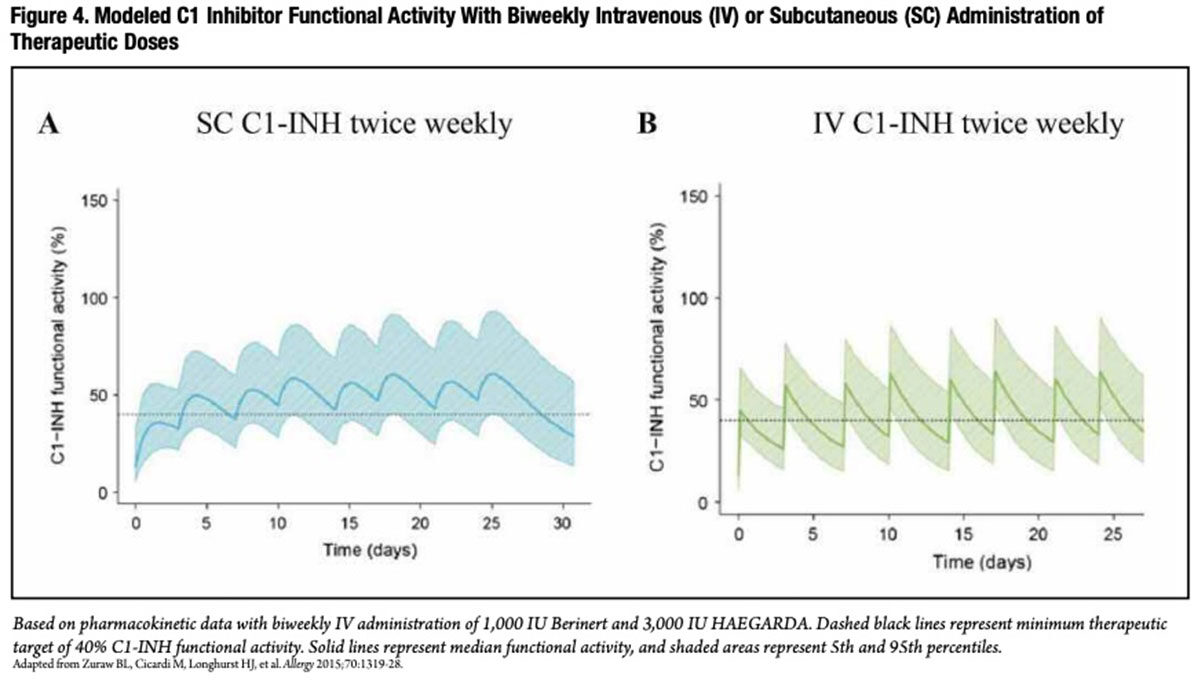

Subcutaneous C1 Inhibitor Prophylaxisfor HAE In nonaffected individuals, circulating C1-INH is naturally maintained at a physiologic, steady-state level. This is not the case with periodic intravenous infusion of a C1-INH concentrate. With a half-life of around 20 hours, the pharmacokinetic profile for twice-weekly intravenous administration of C1-INH exhibits a pronounced saw-tooth pattern, with high peaks following infusion, dropping over several days to much lower trough levels just preceding the next infusion (Figure 4A).15

At a clinically safe therapeutic dose of 1,000 IU, the C1-INH trough level consistently dips below the minimum therapeutic target of 40 percent of normal C1-INH functional activity, the apparent lower threshold for protection against angioedema attacks. Unsurprisingly, a recent study found that, in patients who received twice-weekly intravenous C1-INH prophylaxis, breakthrough angioedema attacks tended to occur shortly before the next scheduled infusion.16 Additionally, technical difficulties with regular venous access often requires the use of indwelling venous catheters, which introduces infection and other risks.

Subcutaneous administration, on the other hand, reduces the “peak-to-trough ratio” and results in more consistent, sustained and higher trough values (Figure 4B). With this understanding, a multinational research team conducted a prospective, randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled Phase III trial to evaluate prophylactic treatment with a self-administered subcutaneous delivery form of a new C1-INH product developed by CSL Behring.17 Over consecutive 16-week periods, two groups of 45 patients self-administered placebo and C1-INH twice-weekly at a dose of either 40 IU/kg or 60 IU/kg.

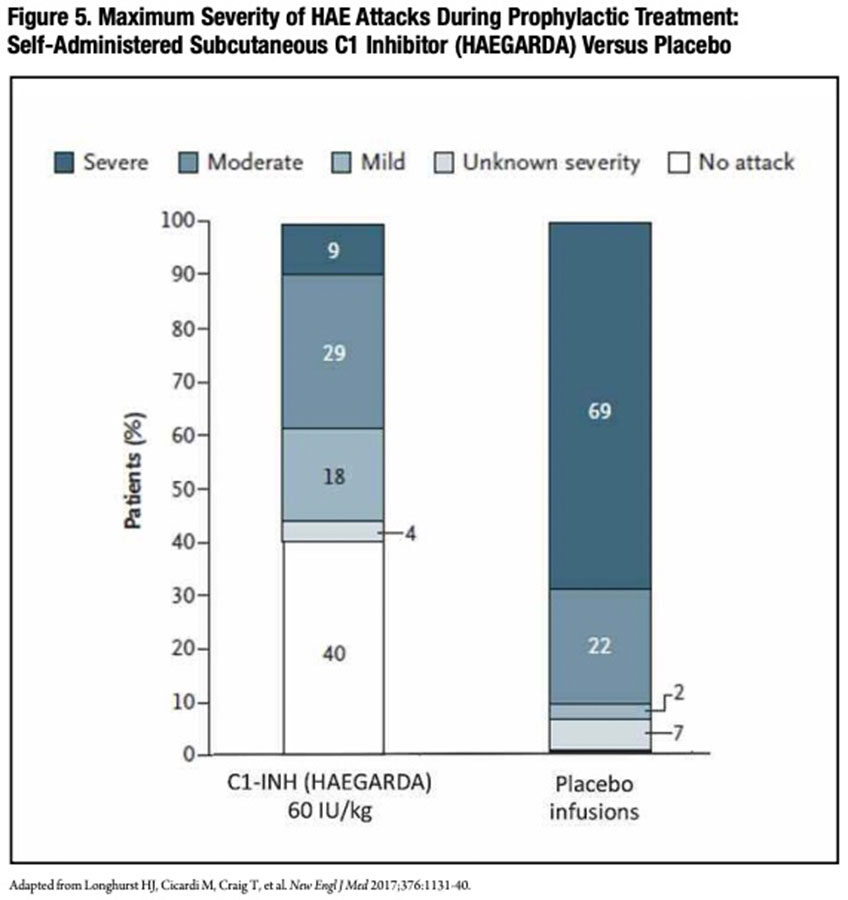

The results were unprecedented. The median reduction in the number of attacks versus placebo was 88.6 percent with a 40 IU dose. There was an even higher 95.1 percent reduction with a 60 IU dose; overall, patients in the 60 IU/kg group had half as many attacks as those in the 40 IU/kg group. Fully 40 percent of patients in the higher-dose group did not experience any attacks over the 16-week treatment period, as compared with no patient who received placebo.

Additionally, the average severity of HAE attacks was dramatically lower with subcutaneous C1-INH prophylaxis than placebo treatment (Figure 5). During their C1-INH treatment period with either dose, just 13 patients had a total of 52 severe attacks, while 64 patients receiving placebo-period treatment had a total of 252 severe attacks. During the 40 IU and 60 IU C1-INH treatment periods, five and zero patients, respectively, experienced a laryngeal attack, compared to 25 patients during placebo treatment. In the 60 IU group, the use of rescue medication to treat attacks was reduced 10-fold during the C1-INH treatment period compared to the placebo treatment period (0.32 vs. 3.89 per month). There were no reported thromboembolic events or any other treatment-related serious adverse events in either C1-INH-dose group.

In June 2017, FDA approved CSL Behring’s novel subcutaneous C1-INH product, brand named HAEGARDA, for routine prophylaxis to prevent HAE attacks in adult and adolescent patients.

Separately, Shire recently announced positive top-line efficacy and safety results from a Phase III trial evaluating a more convenient liquid form of its own new subcutaneously administered C1-INH (SHP616 Liquid). Overall, 78 percent of patients experienced a 50 percent or greater reduction in the HAE attack rate compared to placebo; 38 percent of patients were attack-free during their SHP616 Liquid treatment period, compared to 9 percent during the placebo period. No thromboembolic events or other treatment-related serious adverse events were reported.18

More Treatment Innovations in the Pipeline

The approvals of six new treatments over the last nine years have transformed the management of HAE. But the collaboration between industry and the clinical research community continues with several active initiatives that promise to further reduce or eliminate sudden, disabling angioedema attacks.

CSL Behring is sponsoring an extension study with HAEGARDA to investigate whether individual dosing adjustments can further improve treatment response in patients who continue to experience breakthrough attacks. If approved, Shire’s new liquid, ready-to-use C1-INH product will be a welcomed advance for patients who must now follow multiple steps to reconstitute the product with supplied diluent and a transfer set. Additional approvals of C1-INH products for treatment of children are also anticipated in the near future.

Like hemophilia and primary humoral immunodeficiency disorders, HAE is a rare genetic disease for which replacement therapy with concentrates purified from donor plasma provides safe and highly effective treatment. Looking forward, we can expect more new human plasma-based products that effectively treat other rare genetic disorders with simple replacement of a deficient or dysfunctional blood protein.

References

- Gompels MM, Lock RJ, Abinum M, et al. C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus document. Clin Exp Immunol 2005 Mar;139(3):379-94.

- Gelfand JA, Sherins RJ, Alling DW, et al. Treatment of hereditary angioedema with danazol. Reversal of clinical and biochemical abnormalities. N Engl J Med 1976;295:1444-8.

- Cicardi M, Bergamaschini L, Tucci A,etal. Morphologic evaluation of the liver in hereditary angioedema patients on long-term treatment with androgen derivatives. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1983;72:294-8.

- Frank MM, Sergent JS, Kane MA,etal. Epsilon aminocaproicacid therapy of hereditary angioneurotic edema: a double blind study. N Engl J Med 1972;286:808-12.

- Nzeako UC, Frigas E, Tremaine WJ. Hereditary angioedema: A broad review for clinicians. Arch Int Med 2001 Nov 12;161:2417-29.

- Gadek JE, Hosea SW,Galfand JA,etal. Replacement therapyin hereditary angioedema. Successful treatment of acute episodes of angioedema with partly purified C1 inhibitor. N Engl J Med 1980;302;542-6.

- Agostoni A, Bergmaschini L, Martignoni G, et al. Treatment of acute attacks of hereditary angioedema with C1-inhibitor concentrate. Ann Allergy 1980;44:299-301.

- Craig TJ, Levy RJ, Wasserman RL, et al. Efficacy of human C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate compared with placebo in acute hereditary angioedema attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009 Oct;124(4):801-8.

- Berinert. CSL Behring: Full Prescribing Information, revised 9/2016. Accessed at labeling.cslbehring.com/PI/US/Berinert/EN/BerinertPrescribing-Information.pdf.

- KALBITOR (ecallantide). Shire: Full Prescribing Information, revised 3/2015. Accessed at www.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFs/Kalbitor_USA_ ENG.pdf.

- FIRAZYR (icatibant). Shire: Full Prescribing Information, revised 12/2015. Accessed at pi.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFs/Firazyr_USA_ENG.pdf.

- Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. New Engl J Med 2010 Aug 5;363:513-22.

- CINRYZE. Shire: Full Prescribing Information, revised 12/2016. Accessed at pi.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFs/Cinryze_USA_ENG.pdf.

- Bernstein JA, Relan A, HarperJR,etal. Sustained response ofrecombinant humanC1 esterase inhibitor for acute treatment of hereditary angioedema attacks. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017 Apr;118(4):452-5.

- Zuraw BL, Cicardi M, Longhurst JH, et al. Phase II study results of a replacement therapy for hereditary angioedema with subcutaneous C1-inhibitor concentrate. Allergy 2015 Oct;70(10):1319-28.

- Aygören-Pürsün E, Martinexz-Saguer I, Longhurst HJ, et al. C1 inhibitor for routine prophylaxis in patients with hereditary angioedema: interim results from a European Registry study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137:Ab251 (abstract).

- Longhurst H, Cicardi M, Craig T, et al. Prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks with a subcutaneous C1 inhibitor. New Engl J Med 2017 Mar 23;376(12):1131-40.

- Shire’s Investigational Subcutaneous C1 esterase inhibitor (C1 INH [Human]) Liquid for Injection (SHP616) Significantly Reduces Hereditary Angioedema Monthly Attack Rate Versus Placebo in a Phase 3 Pivotal Trial (news release). Accessed at www.shire.com/en/newsroom/2017/september/cwabkg.

- Zuraw BL, Banerji A, Bernstein JA, et al. US Hereditary Angioedema Association Medical Advisory Board 2013 Recommendations for the Management of Hereditary Angioedema Due to C1 InhibitorDeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013 Sep-Oct;1(5):458-67.