Should There Be a ‘Right to Try’?

The debate surrounding right-to-try laws to allow patients access to potentially life-saving drugs hinges on safety and ethical concerns.

- By Kevin O’Hanlon

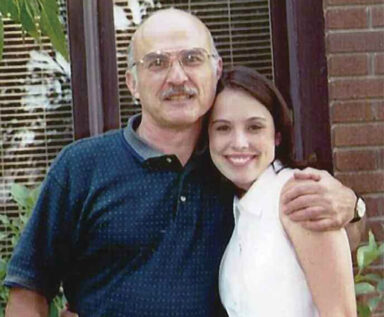

More than four years after Frank Burroughs’ daughter Abigail died of throat cancer, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for use a drug her doctors had hoped could have saved her life. Before she died in 2001, Abigail was being treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore after conventional treatments had failed. Her oncologist suggested that a developmental cancer drug (Erbitux) showed promise, but that FDA approval was far off. The FDA approved Erbitux for use for treating cervical cancer more than three years after Abigail’s death. It approved the drug for treatment of throat cancer about a year after that.

Right-to-Try Laws

The loss of his 21-year-old daughter prompted Burroughs to co-found the Abigail Alliance. The Virginia-based organization is trying to help patients with life-threatening illnesses get access to experimental drugs that have undergone so-called Phase 1 FDA testing1 — the first clinical trial stage where it is determined if the drugs are harmful — but still face years of clinical trials before being approved. The Abigail Alliance is helping to push for so-called “right-to-try” laws — now passed in Arizona, Colorado, Louisiana, Michigan and Missouri — to allow patients to gain access to such potentially life-saving drugs.

Lawmakers in at least 20 states have either introduced or indicated that they will introduce right-to-try legislation this year, according to the Goldwater Institute, a conservative, Arizona-based public policy advocacy/research organization that is one of the champions of the right-to-try movement. Such laws allow a doctor and a patient — provided approved treatment options have been exhausted — to ask a drug company for access to an experimental drug. Colorado’s law, for example, does not mandate that pharmaceutical companies make the drugs available. And it does not require insurance companies to pay for such treatments.2 “You can identify these drugs that are showing genuine solid efficacy early … in clinical trials,” Burroughs said. “It’s an issue of the right to fight for your life.”

FDA’s Role

FDA has not taken a position on any state’s right-to-try legislation. But spokeswoman Stephanie Yao said the agency has a long history of supporting patient access to experimental new treatments by working with drug companies through two pathways:

- enrollment of patients in clinical trials that may eventually lead to FDA approval of the product, and

- through an expanded access program that provides patients with serious or immediately life-threatening conditions when there is no comparable or satisfactory alternative.3

Yao said FDA’s oversight of the process provides important protections for individual patients while also helping to ensure the collection of the data needed to support FDA approval of safe and effective therapies. “While the FDA is supportive of patient access to experimental new treatments when appropriate, we believe that the drug-approval process represents the best way to [ensure] the development of and access to safe and effective new medicines for all patients,” she said.

FDA does not formally track the amount of time it takes to respond to an expanded access request. But data for fiscal years 2010 through 2014 show that FDA has allowed more than 99 percent of expanded access submissions to proceed.4 “The agency often allows these submissions to proceed quickly and, in the case of emergencies, over the phone,” Yao said. She stressed that the 99 percent figure reflects the number of requests submitted to FDA, not the number of patients seeking access to experimental drugs. The figures do not reflect how many patients or physicians do not submit a request because a company refused to provide the drug. “The FDA cannot make a drug company provide a drug to a patient” Yao said.

FDA says expanded access can be granted on a case-by-case basis for an individual patient and to intermediate-size groups of patients (two to 99) who otherwise do not qualify to participate in a clinical trial and for large groups of patients (100 or more) who do not have other treatment options available.5

Safety Concerns and Medical Ethics

The right-to-try movement has spawned concerns over safety, debate over medical ethics and legal action.

In 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal of a federal appeals court ruling (in a case filed by the Abigail Alliance) that said patients do not have a constitutional right to try drugs before FDA approval. R. Alta Charo, a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said allowing patients to use drugs after only preliminary testing puts them at risk of being harmed by the drug — or by the fact that the drug is useless and they “have missed the chance to take something better.”

FDA’s drug-access protocol has been revised several times to make access less logistically complicated. And Yao said if it is still deemed too cumbersome, it can be revised again. In fact, the agency, as recently as 2013, has solicited new comments on the program.

Though manufacturers can’t sell a drug until it has been approved by FDA, they can ask to be reimbursed for their cost if used on an experimental basis. So “they have little or no incentive to provide it at cost to patients who make demands via the right-to-try laws,” Charo said. For example, drug companies may not yet have large supplies of such drugs because they are making only enough for their clinical trials — and scaling up the manufacturing can be expensive. “And without knowing an approval is in the offing from FDA, it is an expense that may never be recouped,” she said, adding that FDA is entitled to information about how the drug worked in every patient who takes it.

Since patients using experimental drugs will not be the same as those in clinical trials — who have been screened for complicating factors — there is a good chance they will have a variety of adverse events, each of which “must be reported to

FDA and considered in the approval process unless clearly unrelated to the drug,” Charo said. That, then, can complicate and slow the process of seeking approval.

Dr. David Gorski of the Science-Based Medicine blog is not a fan of right-to-try laws, which he called “placebo legislation.” “They make legislators feel better but don’t actually do anything,” said Dr. Gorski, an associate professor of surgery at the Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, managing editor of Science-Based Medicine and chairman of the board of directors of the Society for Science-Based Medicine. Dr. Gorski specializes in breast cancer surgery and also serves as the medical director of the Alexander J. Walt Comprehensive Breast Center and as cancer liaison physician for the American College of Surgeons Committee on Cancer.

According to Dr. Gorski, FDA control of drug approval trumps state law, but “there is always the danger that the FDA won’t protect its authority in this matter, and that’s what right-to-try advocates are counting on. Right-to-try laws are far more likely to harm a patient than help, given that the bar is very low. A drug only need have passed a Phase I clinical trial and still be under clinical trials to qualify.” And, said Dr. Gorski, since most Phase I studies only use fewer than 30 patients, “it’s patently absurd to refer to this … as having ‘passed safety testing.’” He said the real goal of right-to-try is to “chip away at the regulatory power of the FDA, based on a fantasy view that there are lots of cures out there if only the FDA would get out of the way and let the free market work its magic. Add to that the fact that these laws provide no financial support, and it is not difficult to imagine patients going broke chasing these cures. Worse, right-to-try gives them no recourse if they are harmed, as patients can’t sue.”

Sascha Haverfield, vice president of scientific and regulatory affairs at the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said her group has “serious concerns with any approach to make investigational medicines available that seeks to bypass the oversight of the Food and Drug Administration and clinical trial process, which is not in the best interest of patients and public health.” Haverfield said successful completion of the clinical trial process is necessary to demonstrate that an investigational medicine is safe and effective, which is required to obtain FDA approval.

The FDA process for a patient to gain access to an investigational drug through expanded access was established in close consultation with patients, physicians and the biopharmaceutical industry, Haverfield said. “Legislation at the state level, however well-intentioned, is unlikely to add any meaningful new approaches that can optimize the federal expanded access process overseen by FDA.” Therefore, it is critical that all stakeholders — patients, physicians, biopharmaceutical companies, academia and FDA — come together to identify ways to improve the existing federal expanded access process and modernize the clinical trial, drug development and FDA review processes “by harnessing 21st century science to accelerate the availability of new medicines for the patients who need them,” Haverfield added.

Proponents Keep Pushing

Kurt Altman, national policy advisor and general counsel for the Goldwater Institute, said proponents of right-to-try “are under no grand illusion that miracle cures exist. They do not guarantee a right to cure. The laws simply give patients the right to try to prolong their lives. They are based on reality, not fantasy.”

Right-to-try does not hamper the clinical trial process — but rather may even complement it, Altman added. “Investigational medicines that are available to terminal patients through right-to-try continue to make their way through the clinical trial process, where additional information is collected,” he said. And, he stressed that if a drug is removed from the clinical trial process, it is no longer available to patients under right-to-try. “In this way, right-to-try patients get the same access that members of the clinical trials get, while doctors and scientists collect even more information,” he said.

Proponents also argue that federal regulations that violate constitutional liberties can never trump state laws. “It is well-established that the U.S. Constitution was designed to provide a floor of protection for individual rights, not a ceiling,” Altman said. State constitutions may provide additional and greater protections to individuals. For example, many states protect speech to a greater extent than the U.S. Constitution, and others provide greater privacy rights. “The right-to-try (laws are) designed to provide the expanded individual right to life by ensuring a right to medical self-preservation,” Altman said. “That right is a liberty so inherent and vital that no government can place limitation on it through regulation or otherwise. Although these medicines may have unknown adverse effects, some even severe, all terminal illnesses have one certain adverse effect: death.”

Burroughs said that every drug for cancer and other serious life-threatening illnesses that the Abigail Alliance has pushed for earlier access in its 13-year history is now approved by FDA. “There is not one drug that we pushed for earlier access to that did not make it through the clinical trial process,” he said. “Many lives could have been saved or extended if there had been earlier access to these drugs.”

While Altman said the FDA’s Expanded Access — or compassionate use — program may be an option, “it isn’t a very viable one” for most terminal patients. “That’s because even the FDA’s own literature estimates that it takes over 100 hours for a doctor simply to complete the initial paperwork required,” Altman explained. “The bureaucracy is so burdensome that fewer than 1,000 compassionate use requests are received by the FDA annually. Meanwhile, over 400,000 people in the United States die from cancer each year.”

According to Burroughs, federal action is needed: “The U.S. Congress needs to get the FDA to move forward and get promising — keyword ‘promising’ — investigational drugs out there to people fighting for their lives sooner. Tens of thousands of people are dying each year that don’t have to. Good grief. It’s this risk-benefit issue. These people have no choices but that. We’re not talking about a new toe fungus cream. We’re talking about people’s lives.” “These patients do not have decades to wait for a drug that could help them now,” Altman adds. “The reality is that when facing a terminal illness, every day, hour, minute and second matters.”

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: CGMP for Phase I Investigational Drugs. Accessed at www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm070273.pdf.

- House Bill 14-1281. Accessed at www.statebillinfo.com/bills/bills/14/1281_enr.pdf.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Final Rules for Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs for Treatment Use and Charging for Investigational Drugs. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/InvestigationalNewDrugINDApplication/ucm172492.htm.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Expanded Access INDs and Protocols. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/DrugandBiologicApprovalReports/INDActivityReports/ucm373560.htm.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Expanded Access: Information for Patients. Accessed at www.fda.gov/forpatients/other/expandedaccess/default.htm.