The Evolution of Medical Aid in Dying

The right-to-die movement advocating the passage of state legislation to allow medical aid in dying is gaining momentum.

- By Diane L.M. Cook

THE RIGHT-TO-DIE movement started in the United States in the 1980s, when the Hemlock Society was formed and Jack Kevorkian, MD, offered his “death counseling” services. Prior to that, the movement had progressed very slowly. It took 91 years from the time the first euthanasia bill was drafted and subsequently defeated in Ohio in 1906,1 until Oregon passed its Death with Dignity Act (DWDA) in 1994 that went into effect in 1997.2 The DWDA was the first aid-in-dying statute in the United States.

Public support for the right-to-die movement has increased in the U.S., mainly due to a change in terminology. In 1996, the American College of Legal Medicine (ACLM) rejected the term “physician-assisted suicide,” claiming it “unfairly colors the issue, and for some, evokes feelings of repugnance and immorality.” In 2008, ACLM was the first organization to publicly advocate elimination of the word “suicide” from the term.3 Today, mentally competent, terminally ill persons who choose to hasten their death with the assistance of their attending physician are no longer referred to as committing suicide or engaging in physician-assisted suicide, physician-assisted death, mercy killing or euthanasia. The medical practice is now referred to as medical aid in dying (MAID).

While public support for MAID has increased over the decades, as evidenced by a 2014 poll that showed three of four Americans (74 percent) agreed “individuals who are terminally ill, in great pain and who have no chance for recovery have the right to choose to end their own life,”4 several groups continue to prevent states from passing MAID legislation. Indeed, political parties, religious groups and the medical community have all been instrumental in restricting the right-to-die movement. While MAID legislation is passed at the state level, in 2008, the federal Democratic Party position stated it is “silent on euthanasia and assisted suicide,” and the federal Republican Party position stated: “We believe medicines and treatments should be designed to prolong and enhance life, not destroy it. Therefore, federal funds should not be used for drugs that cause the destruction of human life. Furthermore, the Drug Enforcement Administration ban on use of controlled substances for physician-assisted suicide should be restored.”5

A summary of religious groups’ views on end-of-life issues, including physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia, released by the Pew Research Center in 2013, showed 14 of 16 major American religious groups opposed any form of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.6 And, the June 2016 edition of the American Medical Association’s Code of Medical Ethics states: “Permitting physicians to engage in assisted suicide/euthanasia would ultimately cause more harm than good.” In addition, it continues: “Physician-assisted suicide/euthanasia is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer … and … instead of engaging in assisted suicide/euthanasia, physicians must aggressively respond to the needs of patients at the end of life.”7

Even so, since Oregon’s DWDA went into effect, individuals and right-to-die organizations have done much to change the landscape of MAID.

Brittany Maynard’s Story

Brittany Maynard, a California resident, put a face on the right-to-die movement. Maynard was a teacher who loved to travel. She married Dan Diaz in September 2012, and she looked forward to starting a family. But in January 2014, Maynard was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. In March 2014, she was given six months to live. She was only 29 years old.

At the time of Maynard’s terminal diagnosis, California did not have MAID legislation. After she learned from her oncologist she would endure unremitting pain and seizures in her final days, which would cause terrible trauma to herself and her loved ones, Maynard and Diaz moved to Oregon to take advantage of the DWDA.

The DWDA allows terminally ill Oregon residents to apply for and receive from their attending physician a lethal prescription of medication, which they must consume themselves to hasten their death. The DWDA gave Maynard the option to end her life with dignity before it became unlivable.

Between the time Maynard and Diaz settled in Oregon, and her passing on Nov. 1, 2014, she became a strong advocate for the legalization of MAID. “During the last six months of Brittany’s life, she spoke up and lent her voice to the issue of medical aid in dying because she felt it was an injustice that we had to move from our home for her to have the option of a gentle dying process,” said Diaz. “Her message was aimed primarily at legislators so that no one else would have to endure leaving their home, like she did, after being told they have six months to live.”

Three years after Maynard’s passing, Diaz continues to advocate for MAID legislation and has traveled to more than a dozen state capitals to provide testimony at Senate hearings where MAID legislation is moving forward. “I share the reality of what medical aid in dying means to a terminally ill individual,” he explains. “I also dispel the myths and false narratives that the opposition bring forward. Their campaign is based on fear and attempts to slow the passing of the legislation.”

Diaz believes laws that govern medical issues should not be based on religious beliefs: “To be fair to persons of all religions, and those who may not subscribe to any religion, laws should not align with a particular religious doctrine. The strength of medical aid in dying legislation is that it’s an option which a terminally ill person has to apply and qualify for by meeting strict criteria. The passage of medical aid in dying legislation does not affect terminally ill persons who are opposed to the practice for their own religious beliefs. A person who opposes medical aid in dying legislation would simply never avail themselves of the option.”

Diaz says improvements in medical training are needed for end-of-life care that should include a clear understanding of MAID. “Medical professionals are trained to help patients become well again, almost at any cost. They sometimes offer specific treatments to terminally ill patients they know will not work, but feel obligated to offer anyway,” says Diaz. “Early in medical school, doctors in training need to be reminded that we’re all mortal, and we will all eventually die. Therefore, terminally ill persons need to be provided with information on treatment options to make informed medical decisions for their end-of-life care. Unwanted or unnecessary treatment could prolong a person’s dying process and cause them more suffering.”

Oregon’s DWDA

Oregon’s DWDA is a death with dignity law written by founding members of the Death with Dignity National Center, a nonprofit organization that campaigns, lobbies and advocates for MAID legislation in states that currently lack it. Peg Sandeen, executive director of the organization, says not only was Oregon’s DWDA the first law of its kind in the United States, it was the first law of its kind in the world, and it has the most restrictive requirements a terminally ill person must meet.

Sandeen explains the defining difference between the DWDA and euthanasia: “The Death with Dignity Act allows for terminally ill Oregon residents to obtain a lethal prescription from their physician for self-administration. In medical aid in dying, the terminally ill person controls their dying process from beginning to end. There are currently five states and Washington, D.C., that have medical aid in dying statutes. Euthanasia is where a physician or other person directly administers a medication to end another’s life. Euthanasia is illegal in all 50 states in the United States.

“The Death with Dignity Act sets medical issues apart from dying issues, and allows a terminally ill person to live until they decide it’s time for them to die. The Death with Dignity Act created a right for one special group, the terminally ill, but it protected everyone else — including persons who are not terminally ill or who are not of sound mind or are unable to make end-of-life decisions for themselves.”

According to Sandeen, the DWDA has helped to change everything about the landscape of MAID: “The DWDA codified the medical standard of care as it relates to what a physician does to help their terminally ill patients hasten their death. Physicians were already helping their terminally ill patients die, but the process was somewhat unregulated. In Oregon, we wrote down these steps for physicians to follow.

“The quality of dying has also improved since the Death with Dignity Act came into effect. There are more signed advanced directives and Provider Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, hospice usage is higher, there is more support for terminally ill patients’ desire to hasten their death, and more terminally ill people are dying at home.

“Although the DWDA was originally passed under Oregon’s Measure 16 ballot in 1994, the law did not come into effect until 1997. Oregon now has 20 years of irrefutable data that shows the law is working as it was intended to. There is also data now available from California and Washington state which show their respective death with dignity laws are working in those states as the law was intended, as well.”

Since the DWDA came into effect, five more states and The District of Columbia have passed death with dignity laws. Washington passed the Death with Dignity Act in 2008, Vermont passed the Patient Choice and Control at the End of Life Act in 2013, California passed the End of Life Option Act in 2016, Colorado passed the End of Life Options Act in 2016, and the District of Columbia passed the Death with Dignity Act in 2017. Montana does not have a death with dignity statute. However, in 2009, Montana’s Supreme Court ruled nothing in the state law prohibited a physician from fulfilling a terminally ill patient’s request by prescribing lethal medication to hasten his or her death.8

Sandeen says the organization is currently working with grassroots groups and nonprofit organizations in Hawaii, Maine, New York, Ohio and Texas, as well as advocates in several other states to help pass death with dignity laws.

Compassion & Choices

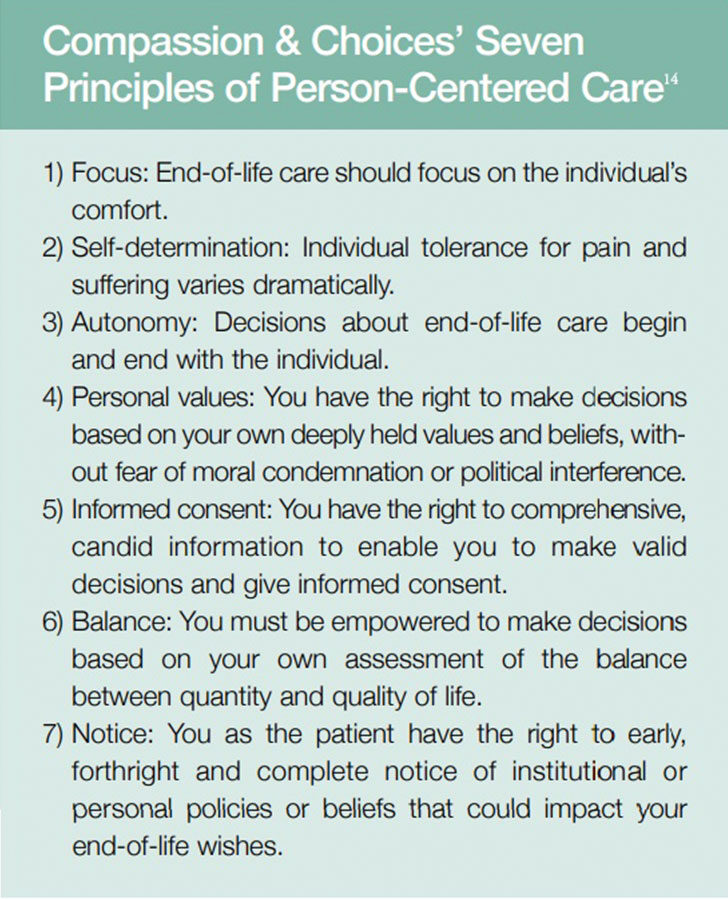

As part of her advocacy for MAID legislation, Maynard partnered with Compassion & Choices. Predicated on the Seven Principles of Person-Centered Care, Compassion & Choices has worked for more than 30 years to improve healthcare and expand options for end-of-life care. The organization works to advance policies that allow people to make fully informed decisions about their healthcare, including to improve pain management, end unwanted or unnecessary medical treatment, improve hospice and palliative care, and help to enact MAID legislation.

Barbara Coombs Lee, president of Compassion & Choices, was an emergency room and intensive-care unit nurse and physician assistant for 25 years before she became a private attorney and counsel to the Oregon State Senate. Coombs Lee co-authored Oregon’s DWDA and served as its chief spokesperson through its two statewide ballot campaigns in 1994 and 1997.

Coombs Lee says Compassion & Choices’ most important accomplishment has been to put MAID into a medical context. “Intentional dying used to be considered separate from medical care,” she says. “However, it’s become a pivotal point for a terminally ill patient to approach their attending physician and ask for medical aid in dying. Doctors should be up-front with their patients in terms of their prognosis and their treatment. And if the doctor says, ‘I can’t help you,’ it doesn’t mean they can’t help the patient at all. Rather, doctors should be able to help their patients through their dying process.”

Maynard was an example of the kinds of decisions a terminally ill patient is able to make if they ask questions about the course of their illness and peaceful death options available to them, says Coombs Lee. “Compassion & Choices developed the first national end-of-life consultancy program in 1993, which offers patient tools, information and emotional support for end-of-life options,” she explains. “We also pioneered the use of and transformed advance directives from strictly legal documents to a values-based approach for communicating end-of-life priorities.”

Maynard’s partnership with Compassion & Choices began on Oct. 6, 2014, with the launch of her six-minute YouTube video explaining her decision to hasten her death and advocate for proposed legislative change in her home state of California.9 Her video was watched by almost 12 million people, generated worldwide media attention and, eventually, led to California passing the End of Life Option Act in 2016.

The partnership also resulted in the creation of the Brittany Maynard Fund,9 an Internet site where people can go to donate to and lend their voice and support for the MAID cause. “People can make contributions to the fund,” says Coombs Lee. “People can write letters to send to their government officials. People can feel like they are a part of a community of like-minded individuals. People can also see what’s happening in the rightto-die movement and take meaningful action in their own communities.”

A Growing Cause

According to Coombs Lee, Maynard was a worldwide voice for medical aid in dying. In the three weeks between Maynard’s story that appeared in the media and her death, 38 percent of American adults (93 million people) heard her story.10 Maynard’s story was published on People.com on Sunday, Nov. 2, 2014, garnering more than 16.1 million unique visitors and reaching nearly 54 million people on Facebook. It was the biggest story in Time Inc.’s publication history.11 “Brittany changed the perception of medical aid in dying. She made people understand her dilemma and her choices, and people of all ages related to her,” says Coombs Lee.

Diaz says Brittany would feel a great sense of relief to know individuals in other states “now have the medical aid in dying option available to them so they, too, will have the option of a gentle dying process, and they won’t have to move to a state that has medical aid in dying legislation like she had to.”

There are now 27 more states considering enacting MAID legislation. However, says Diaz, it does not mean all 27 states will pass it: “The challenge with passing medical aid in dying legislation is that it can be subject to politicians’ personal religious beliefs. It’s easy for a senator to bring medical aid in dying legislation forward, but it can be hard to get the legislation passed by that state’s legislative body.”

Yet, Diaz believes those in the baby-boom generation who have navigated end-of-life care with their parents, and some of whom are faced with a terminal illness of their own or that of their spouse, will help the right-to-die movement. “Baby boomers won’t tolerate anything less than having all options available to them,” he says. “That determination will be a big benefit with medical aid in dying legislation and will help make headway in getting this legislation passed.”

Sandeen is confident that once a certain number of states have enacted death with dignity legislation, the ball will start rolling, pick up speed and many more states will pass the legislation quickly: “Hopefully, more states will pass death with dignity legislation sooner, in the next 20 years or so, and we won’t have to wait 14 years as we did between Oregon in 1994 and Washington in 2008.”

References

- ProCon.org. 1905-1906 — Bills to Legalize Euthanasia Are Defeated in Ohio. Accessed at euthanasia.procon.org/view.timeline.php?timelineID=000022.

- Oregon Legislature. Chapter 127: Powers of Attorney; Advance Directives for Health Care; Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment Registry; Declarations for Mental Health Treatment; Death with Dignity. Accessed at www.oregonlegislature.gov/bills_laws/ors/ors127.html.

- American College of Legal Medicine. ACLM Policy on Aid in Dying, Oct. 6, 2008. Accessed at c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.aclm.org/resource/collection/11DA4CFF-C8BC-4334-90B0-2ABBE5748D08/Policy_On_Aid_In_Dying.pdf.

- Thompson, D. Most Americans Agree with Right-to-Die Movement: 74 percent Now Believe Terminally Ill Should Have Choice to End Their Lives. HealthDay/Harris Poll, Dec. 5, 2014. Accessed at consumer.healthday.com/mental-health-information-25/behavior-health-news-56/most-americans-agree-with-right-to-die-movement-694268.html.

- Priests for Life. A Comparison of the 2008 Republican and Democratic Platforms. Accessed at www.politicalresponsibility.com/comparison_side2.pdf.

- Pew Research Center. Religious Groups’ Views on End-of-Life Issues, Nov. 21, 2013. Accessed at www.pewforum.org/2013/11/21/religious-groups-views-on-end-of-life-issues.

- American Medical Association. Principles of Medical Ethics,Chapter 5: Opinions onCaring for Patients at the End of Life, 5.7 Physician-Assisted Suicide and 5.8 Euthanasia. June 2016 Report. Accessed at www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-5.pdf.

- Death with Dignity National Center. Current Death with Dignity Laws. Accessed at www.deathwithdignity.org/learn/death-with-dignity-acts.

- Compassion & Choices. Brittany Maynard’s 6-Minute YouTube Video and The Brittany Maynard Fund. Accessed at thebrittanyfund.org.

- Heard about Brittany Maynard. Yes — 38% (93 Million People). YouGov, Oct. 28–30, 2014. Accessed at cdn.yougov.com/cumulus_uploads/document/dl6fbt2baj/tabs_OPI_assisted_suicide_20141030.pdf.

- Sebastian, M. Brittany Maynard Story Leads to Record Digital Traffic for People. Ad Age,Nov. 6, 2014. Accessed at adage.com/article/media/brittany-maynard-story-sets-digital-traffic-record-people/295738.

- Oregon Health Authority. Death with Dignity Act Requirements. Accessed at www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRESEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Documents/requirements.pdf.

- Oregon Health Authority. Death with Dignity Act: Data Summary 2016. Feb. 10, 2017. Accessed at www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year19.pdf.

- Compassion & Choices. The Seven Principles of Person-Centered Care. Accessed at www.compassionandchoices.org/who-we-are.