The Physician Shortage and Its Effects on Healthcare

The dire projection of physician shortages in the U.S. could cause major problems for both patients and healthcare facilities. What's being done to fix it?

- By Ronale Tucker Rhodes, MS

THE UNITED STATES has a significant physician shortage, and projections show it is only going to worsen. According to projections published in March 2024 by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the U.S. will face a shortage of up to 86,000 physicians by 2036.1 Specific projections include shortages of between 17,800 and 48,000 primary care physicians and between 21,000 and 77,100 nonprimary care physicians, including between 15,800 and 30,200 in surgical specialties, between 3,800 and 13,400 in medical specialties and between 10,300 and 35,600 in other specialties.2

While this shortage stands to substantially affect patient access to treatment, it also has the potential to incapacitate healthcare facilities. So, what can be done? Currently, there are many recommendations for how to reduce the shortages. Yet, questions remain as to whether these suggestions will be implemented and if they will work.

Specialties Affected

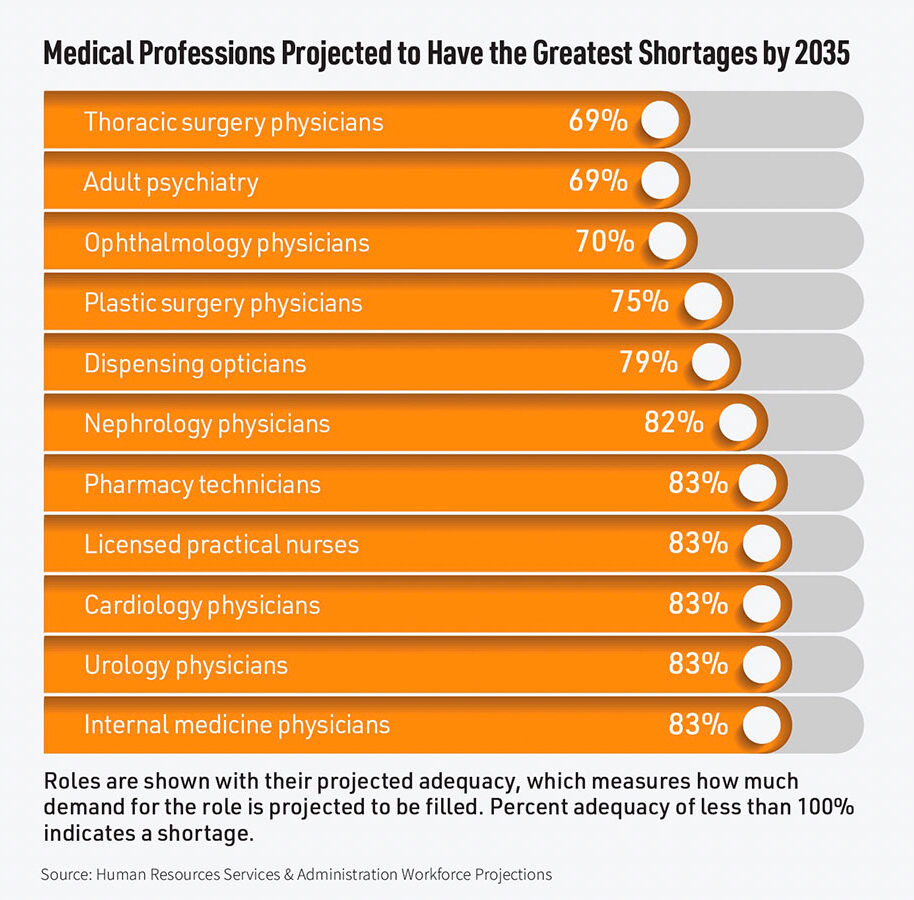

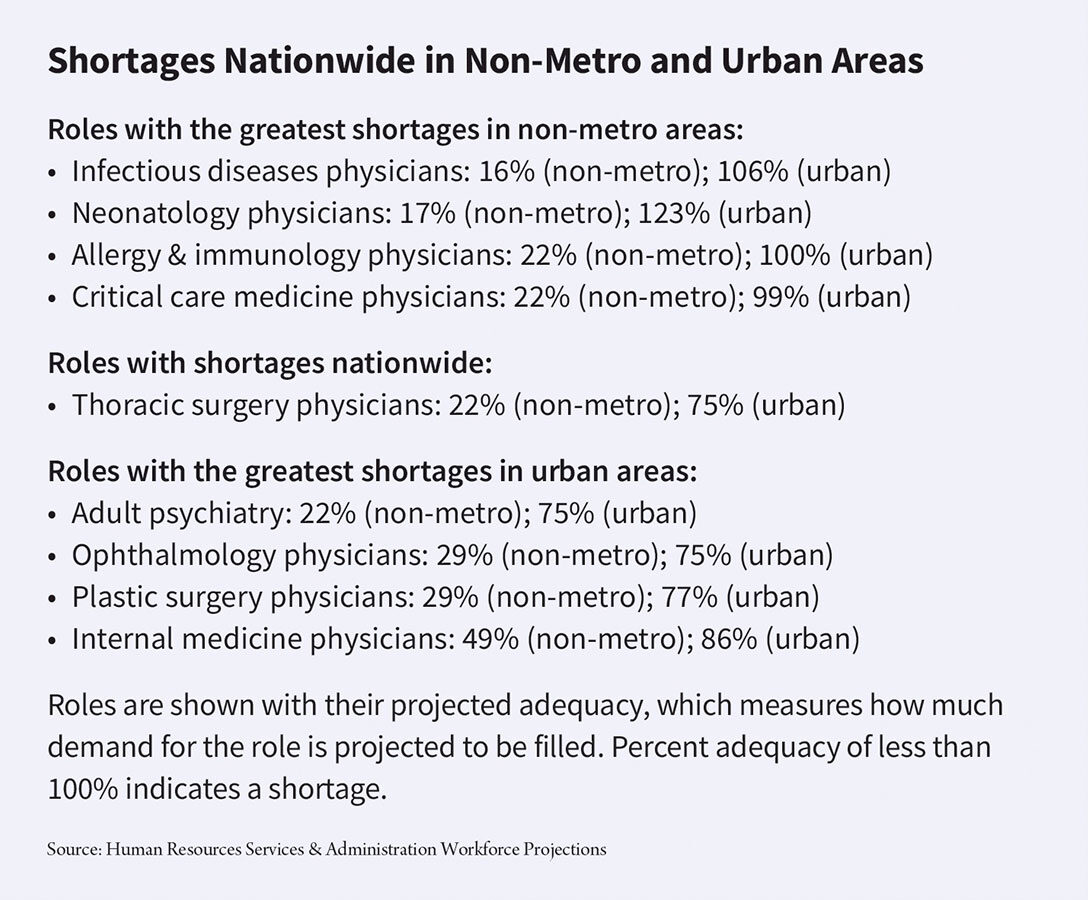

Current and projected physician shortages span all specialties. However, some are much more pronounced than others. Ranked by the percent of demand (supply divided by demand), physician specialties that will be most affected by shortages include, in order, thoracic surgeons (69 percent), ophthalmologists (70 percent), plastic surgeons (75 percent), nephrologists (79 percent) and urologists (83 percent).2

What’s more, according to the American Medical Association (AMA), “about 83 million Americans live in areas that don’t have sufficient access to a primary care physician.” AMA also states that “in large parts of Mississippi and Idaho, pregnant women can’t find obstetricians. Across the nation, 90 percent of counties don’t have a pediatric ophthalmologist; 80 percent of counties don’t have an infectious disease specialist; [and] more than one-third of Black Americans live in a cardiology desert.”

“The physician shortage that we have long feared and warned was on the horizon — it’s already here and it’s hitting every corner of this country, urban and rural, with the most direct impact hitting families with the highest needs and the most limited means. While the physician shortage is a crisis today, there is reason to believe it’s going to get a lot worse unless we take immediate actions to address it,” AMA President Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH, said during an AMA webinar about what’s exacerbating the physician shortage crisis and what’s needed to fix it.3

Reasons for Shortages

The main problem behind these shortages is that they are due to not just one or two reasons, but to a host of them that are not easy to overcome.

According to McKinsey & Company, a consultant firm that helps private and public healthcare leaders make healthcare better, more affordable and more accessible for millions of people around the world, one reason for the projected shortage is that approximately 20 percent of clinical physicians are aged 65 years or older, which means healthcare organizations may soon lose a substantial number of physicians to retirement.4

In July 2023, McKinsey conducted its seventh physician survey to understand the mindsets that are pushing doctors in the United States out of the workforce. The survey found that more than a third of the 631 physician respondents are likely to leave their jobs in the next five years, and that number is not limited to those approaching retirement age. Fifty-nine percent of those aged 54 to 64 said early retirement or leaving the care delivery workforce is their most likely next step, and 13 percent said they would prefer to move to an administrative role within the care delivery workforce.4

When asked what factors were influencing their desire to leave healthcare, 69 percent cited higher pay, family needs and competing life demands. The demanding nature of the job, emotional toll and physical toll of work (66 percent, 65 percent and 61 percent, respectively) were also key determinants.4 In fact, physicians are increasingly facing burnout caused by increased workloads and decreased support. Fifty-two percent of the survey respondents said they work more than 60 hours per week, and 66 percent of those are dissatisfied with their schedules.4

Burnout is also high on the list of reasons physicians are leaving the medical profession. According to Dr. Ehrenfeld, “There is an insidious crisis going on in medicine today that is having a profound impact on our ability to care for patients, and yet isn’t receiving the attention it deserves. This crisis is physician burnout … Physicians everywhere — across every state and specialty — continue to carry tremendous burdens that have us frustrated, burned out, abandoning hope … and in increasingly worrying numbers, turning our backs on the profession we’ve dedicated our lives to.”5

Other issues affecting physician shortages are the length of time required to complete medical training, a lack of medical residency programs, the exorbitant cost of medical school and the time it takes for foreign-trained physicians to practice medicine in the U.S.

According to Continuing Education Company (CEC), an independent non-profit that develops and provides educational opportunities to improve the skills and knowledge of medical and healthcare professionals, “In the time between graduating high school and entering the workforce as a doctor, over a decade passes. The U.S. medical training programs take significantly longer — 11 years at minimum — than other countries. That’s going to hurt us. To be ready for the doctor shortage we’ll be facing in 2034, we’d need to have already started training those physicians.”6

And, while medical school enrollments have increased, residency slots haven’t kept pace due to a congressionally imposed cap on federal funding for graduate medical education (GME) through the Medicare program, which is the largest public contributor to GME funding.7 GME is the formal medical education needed after earning a medical degree. “Without more funding for residency programs, the final step in the physician-training process will remain a bottleneck,” says CEC.6

The high cost of medical education and subsequent debt burden for physicians are contributing significantly to physician shortages. This is true particularly in primary care and rural areas. “The average young doctor now leaves medical school more than $250,000 in debt,” says Dr. Ehrenfeld. And, “Foreign-trained physicians, called International Medical Graduates or IMGs, face enormous obstacles — such as immigration and green-card delays — to practice medicine in the U.S.”5

Impact on the Healthcare Profession

While physician burnout was high even before COVID-19, the pandemic-turned-endemic has only exacerbated the problem due to increased workloads. According to a report by AAMC titled “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036,” the organization estimated (based on another report from McKinsey & Company) a 2.2 percent increase in demand for primary care visits in each future year; a 3,476 full-time-equivalent (FTE) increase in demand for primary care physicians (as well as an increase in demand for nurse practitioners [NPs] and physicians assistants [PAs] in primary care); and a 1.5 percent increase in demand for hospital services, or approximately 591 FTE hospitalists, 224 FTE critical care physicians and 691 FTE physicians across other specialties (e.g., cardiology, endocrinology, infectious diseases, pulmonology, nephrology) in 2021. In total, the report stated COVID-19 hospitalizations increased physician demand by about 1,507 FTEs in 2021, with similar levels projected in future years — all a result of acute COVID-19 implications as it shifted from a pandemic to an endemic.8

What’s more, the report estimates that three percent of COVID-19 cases will result in long COVID lasting three to 12 months, or about 6.6 million visits annually that, if proportionately distributed across physicians in family medicine, internal medicine, geriatric medicine, neurology, pulmonology, cardiology, infectious diseases, nephrology and endocrinology, would result in a one percent increase in annual visits to each of these specialties.8

Add to all this the expanding gap in the physician workforce, says an article posted on the McKinsey & Company website, “which is particularly consequential given the projected growth in patient demand: The number of people aged 65 and up — an inherently higher-need patient group — is expected to rise to 23 percent of the population, from 17 percent, by 2050.”

With rising demand and a decreasing physician supply, it is difficult for healthcare organizations to recruit the most talented physicians and specialists. According to an article published by StaffMed Health Partners, hiring cycles have lengthened, with primary care physician positions taking about 125 days to fill and specialist positions taking up to 135 days to fill on average. And, recruiting in rural areas is even more challenging post-pandemic.10 However, the Association for Advancing Physician and Provider Recruitment’s (AAPPR) annual Internal Physician and Provider Recruitment Benchmarking Report in 2024, which highlights search dynamics and trends within physician and provider recruitment and their impact on recruiting and hiring in healthcare, shows the percentage of filled searches has increased for the first time in five years. Still, the report’s findings highlight continued challenges:11

• After decreasing in 2022, the percentage of offers accepted increased in 2023 for both physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs). On average, APPs accepted 71 percent of offers extended to them, and physicians accepted 83 percent of their offers.

• In 2023, the median time to hire physicians — measured from search launch to signed contract — varied widely by specialty, spanning 77 to 228 days.

• Turnover among physicians and APPs has decreased year-over-year, but is still higher than 2019 and 2020.

Facilities need to consider the costs of losing a key physician without a replacement lined up. “The estimated lost revenue for a noninvasive cardiologist opening that sits vacant for six months is about $1.15 million,” said Tara Osseck, MHA, regional vice president of recruiting at Jackson Physician Search. “A gastroenterology vacancy sitting open for the same amount of time is about $1.4 million. … An ophthalmology vacancy is the equivalent of $1.6 million in lost revenue.” Beyond the lost revenue of physician vacancies, added Osseck, other major implications include “lost market share, the effect of burnout on other physicians and providers trying to make up for the vacancy, and added costs from using a locum tenens provider while the search for a permanent replacement is underway.”12

Physician recruitment battles have the potential to hurt an organization’s finances. Statistics compiled by CompHealth, a staffing firm for healthcare employers, found physician vacancies cost hospitals between $7,000 and $9,000 in lost revenue per day. And, with the average physician vacancy lasting 195 days and the typical facility having 87 vacancies annually, the effects can add up quickly. In addition, in a poll of medical group leaders conducted by the Medical Group Management Association, more than three quarters (78 percent) said “the amount of time they spend on recruitment and interviewing candidates increased in the past year, while about 16 percent reported their time commitment stayed the same, and only six percent managed to decrease their time spent in this area.13

Combating Shortages at the Physician Level

Physicians might actually be compelled to remain in the healthcare profession if certain needs of theirs could be met. And, Dr. Ehrenfeld has made some specific recommendations:5

• Provide physicians with annual payment updates to account for practice cost inflations as reflected in the Medicare Economic Index that would put physicians on equal footing as inpatient and outpatient hospitals, skilled nursing facilities and others who receive payment through Medicare.

• Expand residency training options, provide greater student loan support and create smoother pathways for foreign-trained physicians who already comprise about one-quarter of the nation’s physician workforce.

• Reduce administrative burdens such as the prior authorization process that insurers use to try to control costs, requiring physicians and their staff to spend an average of two business days a week completing prior authorization paperwork, including submissions and appeals when insurers inappropriately deny care for treatments already in wide use.

• Make sure physicians aren’t punished for taking care of their mental health needs that often make physicians reluctant to seek help for their mental health over fears it will jeopardize their license or employment because of outdated and stigmatizing language on medical board and health system application forms that ask about a past diagnosis.

To address family needs and competing life demands, an April 4, 2023, MGMA Stat poll found that almost half (47 percent) of medical group leaders added or created part-time or flexible-schedule physician roles in the past year; unfortunately, 53 percent did not. The poll had 470 applicable responses. But, as Osseck noted about offers for improved benefits packages or the promise of a better work-life balance in a flexible scheduling scenario: “Physicians now know their financial worth more than ever … and they’re deciding for themselves how their current positions stack up.”12

The Role of Organizations and Government

AAMC leads the GME Advocacy Coalition (GMEAC), “a group of over 100 physician, hospital and patient care organizations dedicated to the expansion and preservation of Medicare-supported graduate medical education,” whose efforts are making progress in meeting the nation’s projected healthcare needs. Medical schools have increased enrollment by more than 35 percent since 2002, and 15 percent in the past 10 years. Enrollment numbers at medical schools are currently at historic highs, and more than 30 new MD-granting medical schools have opened since 2002.14

However, once medical students graduate, they must obtain GME slots to continue in their profession. And this continues to be hampered by the number of GME slots available. Why? In 1996, a physician surplus was deemed a consequence of Medicare’s open-ended subsidies. In response, the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 capped the number of residents GME programs could train. Yet, despite a physician shortage today, GME structures have mostly remained unchanged.

In August 2024, a bipartisan group of eight members of the Senate Finance Committee released a policy outline to expand and improve upon Medicaresupported GME residency training positions in rural and underserved areas, as well as in specialties facing the biggest shortages. This effort was followed by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 that provided 1,000 new Medicare-supported GME positions, the first increase of its kind in nearly 25 years, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 that provided 200 federally supported GME positions for psychiatry and psychiatric subspecialty residencies. However, more federal assistance is needed to substantially increase the number of physicians.15

According to Nicole C. McCann, a PhD candidate in health services and policy research at Boston University School of Public Health, and Rochelle Walensky, an executive fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and at Harvard Business School, and the former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Each year, thousands of medical school graduates don’t match to residency, with lower match rates in rural settings and in financially less-lucrative specialties such as family medicine and primary care. The need for more primary care doctors in underserved rural regions is widely recognized, and physicians often practice where they train. Even so, of the $16.2 billion Medicare budget for GME in 2020, only 2 percent of Medicare-funded resident training slots were located in rural areas — areas where 18 percent of the U.S. population resides.”16

The Senate Finance Committee working group proposes creating additional Medicare GME slots from fiscal year 2027 through 2031. AMA and 46 other organizations that are part of the GME Advocacy Coalition are also making additional suggestions to the Senate Finance Committee to strengthen its draft policy, including:15 15 percent of new Medicare GME slots toward primary care residencies and psychiatry or psychiatric subspecialty residencies, respectively;

• Amending the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 GME-allocation formula by changing the definition of “rural hospitals” to include hospitals that are in rural areas, serve geographic health profession shortage areas, exceed their Medicare full-time employee cap and located in states with new medical schools or branch campuses; and

• Allowing patients to receive telehealth services regardless of their geographic location.

Physician Workforce Projections

AAMC, in collaboration with RAND, has developed a physician workforce projections model that “will eventually allow for more rapid and insightful projections that take into account shifts in both provider and patient populations and behaviors. Preliminary findings from this new model … suggest that task shifting may greatly decrease the shortage of primary care physicians but have less of an impact on other specialties.” According to AAMC, “nonprimary care physician specialty workforce will experience shortages for the next three decades at least.” The organization was expected to release a full report in early 2025, with early data projections showing the rapidly increasing supply of NPs and PAs meeting the demand for providing primary care to the U.S. population within the next decade.17

Yet, even with these projections, as well as efforts by medical organizations and government officials, it seems inevitable that physician shortages are here for the foreseeable future.

References

- New AAMC Report Shows Continuing Projected Physician Shortage. Association of American Medical Colleges press release, March 21, 2024. Accessed at www.aamc.org/news/press-releases/new-aamc-report-shows-continuing-projected-physician-shortage.

- Trusted Talent. Prepare for the Future of Your Facility’s Staffing Needs with Our Review of Projected Physician Shortages by Specialty, Aug. 15, 2024. Accessed at www.trustedtalent.com/managed-services-programs/physician-shortage-by-specialty.

- Henry, TA. All Hands on Deck Needed to Confront Physician Shortage Crisis. American Medical Association, June 10, 2024. Accessed at www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/sustainability/all-hands-deck-needed-confront-physician-shortage-crisis.

- McKinsey & Company. U.S. Physician Survey, July 14, 2023. Accessed at www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/the-physician-shortage-isnt-going-anywhere.

- AMA President Sounds Alarm on National Physician Shortage. American Medical Association, Oct. 25, 2023. Accessed at www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-president-sounds-alarm-national-physician-shortage.

- Continuing Education Company. How the Doctor Shortage Will Impact Healthcare Organizations. Accessed at www.cmemeeting.org/articles/preparing-for-the-doctors-shortage.

- Biggs, DL. What Hospitals Need to Know About the New Graduate Medical Education Legislation. PYA, March 9, 2022. Accessed at www.pyapc.com/insights/what-hospitals-need-to-know-about-the-new-graduate-medical-education-legislation.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036 Summary Report, March 2024. Accessed at www.aamc.org/media/75231/download?attachment.

- Medford-Davis, L, Malani, R, Snipes, C, and Du Plessis, P. The Physician Shortage Isn’t Going Anywhere. McKinsey & Company, Sept. 10, 2024. Accessed at www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/the-physician-shortage-isnt-going-anywhere.

- Claudio, C. Physician Recruitment & Workforce Trends 2025. StaffMed Health Partners, Feb. 7, 2025. Accessed at www.linkedin.com/pulse/physician-recruitment-workforce-trends-2025-christian-claudio-mba-hzsmc.

- Physician Demand Stables Amid Rising Turnover for Recruitment Professionals, According to AAPPR Report. Association for Advancing Physician and Provider Recruitment press release, Oct. 29, 2024. Accessed at www.wate.com/business/press-releases/cision/20241029DE42957/physician-demand-stabilizes-amid-rising-turnover-for-recruitment-professionals-according-to-aappr-report.

- Harrop, C. Physician Shortages Forcing Medical Group Leaders to Be More Flexible in Their Staffing Models. Medical Group Management Association, April 6, 2023. Accessed at www.mgma.com/mgma-stats/physician-shortages-forcing-medical-group-leaders-to-be-more-flexible-in-their-staffing-models.

- 21 Statistics that Summarize the Cost of Healthcare Recruiting and Retention. Intelliworx, Nov. 15, 2023. Accessed at intelliworxit.com/blog/healthcare-recruiting-retention.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Addressing the Physician Workplace Shortage. Accessed at www.aamc.org/advocacy-policy/addressing-physician-workforce-shortage.

- Lubell, J. Powerful Senate Committee Takes Up Physician Shortage. American Medical Association, Aug. 7, 2024. Accessed at www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/sustainability/powerful-senate-committee-takes-physician-shortage.

- McMann, NC, and Wilensky, R. The First Step to Addressing the Physician Shortage. Stat, Jan. 15, 2025. Accessed at www.statnews.com/2025/01/15/physician-shortage-gme-residency-specialties-setting-limitations.

- Grover, A, and Dill, M. New Workforce Model Suggests Continued Physician Shortages in Nonprimary Care Specialties, Nov. 13, 2024. Accessed at www.aamcresearchinstitute.org/news/closer-look/new-workforce-model-suggests.