Payments for Healthcare: A New Day Is Coming

- By BSTQ Staff

In late January, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced that it would fundamentally reform how it pays providers for treating Medicare patients in the coming years. For the most part, the announcement was seen as a positive step that focuses on the quality of care delivered rather than the quantity. Speeding up the transition from fee-for-service to pay-for-performance and forcing Medicare to commit to this payment method were applauded.

New payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments that reward value, improve patient outcomes and cut down on the volume of unnecessary procedures are being pushed with a new fast-paced implementation time frame. The goal? A move from the 20 percent of Medicare payments that currently come from alternative payment programs to 30 percent by the end of 2016 and 50 percent by the end of 2018.

Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network

A variety of partners will work with a new group, the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network, to expand alternative payment models into their programs. The network held its first meeting in March. In addition, HHS is expected to ramp up efforts to work with states and private payers to facilitate the adoption of alternative payment models.

According to a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) fact sheet, HHS has broken down the framework into categories based on how providers will receive payment:

Category 1: fee-for-service with no link of payment to quality

Category 2: fee-for-service with a link of payment to quality

Category 3: alternative payment models built on fee-for-service architecture

Category 4: population-based payment Value-based purchasing includes payments made in categories 2 through 4. Moving from category 1 to category 4 involves two shifts: increasing accountability for both quality and total cost of care, and a greater focus on population health management as opposed to payment for specific services.

HHS believes that with alternative payment models like ACOs that have been up and running since 2011, an estimated 20 percent of Medicare reimbursements had already shifted to

categories 3 and 4 by 2014.1

Is this just another government program? No. Insurers are surging ahead as well with newly defined plans. Most notable are Anthem and United Healthcare. According to Forbes, Anthem wants to transition away from the traditional fee-for-service model toward value-based payments by focusing on enhancing payments for performance and shared-risk arrangements that change the interactions between insurers and providers.2 Similarly, UnitedHealth is involved in implementing value-based payments such as the one announced in late 2014: a new bundled payment program that will pay MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston a flat fee to provide head and neck cancer care.3

Quality is Vital

The quality and accuracy of providers’ use of ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, how they handle reimbursement through the revenue cycle, their adherence to prior authorizations, local coverage determinations (LCDs) or national ones (NCDs), as well as documentation and medical records, are vital. Use of these codes is the only way of telling the patient’s story completely and accurately.

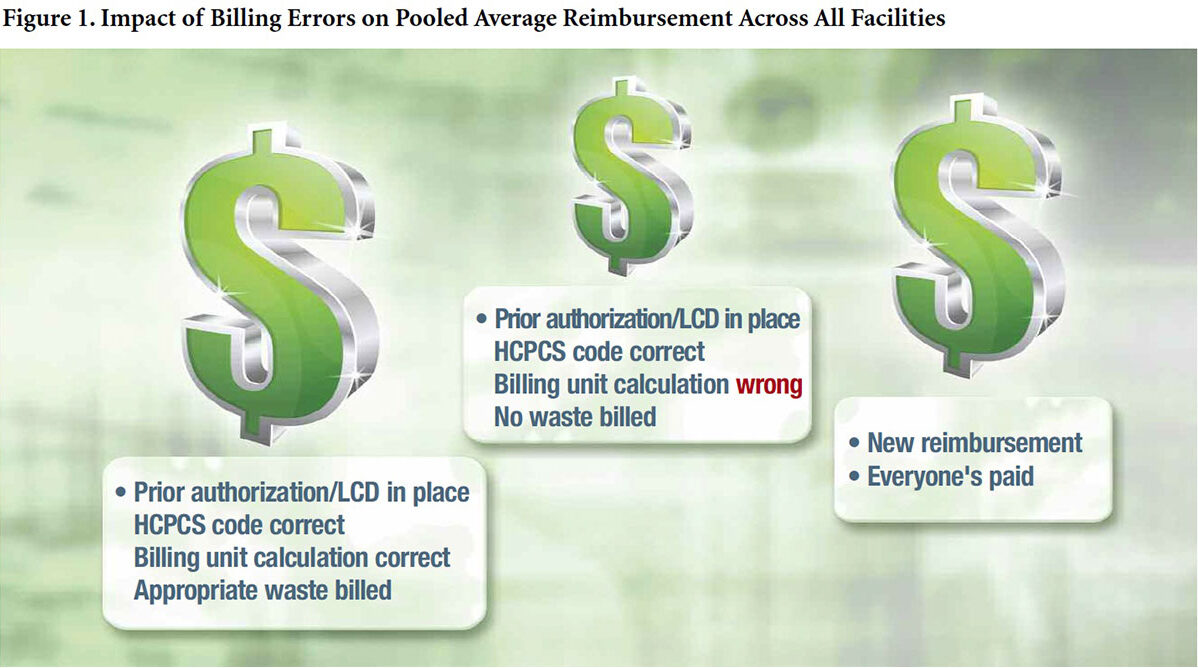

These new payment mechanisms are based on cumulated big data pools. While these payment mechanisms apply to all aspects of care, the remainder of this column will focus on medications. From a pharmacy perspective, cumulated data pools mean that all drugs and drug administration fees billed in the recent past form the basis of the drug components of the new offerings. Providers need to be confident that theirs are accurate, or they may be complicit in billing errors and misrepresentation of cost.

Complicity refers to the act of helping someone else behave inappropriately or illegally either deliberately or accidentally because of lack of attention or failure to look for and correct problems. It’s not uncommon for providers to find themselves complicit concerning the rates of reimbursement for products and services. Many times, they are unaware there are problems in their infrastructure, which often include failing to pay strict attention to billing systems for drug products and drug administration fees; failing to use appropriate codes, descriptions and billing unit conversions; neglecting to bill for some drugs at all because it’s “too complicated for too little return” (these patients and products get averaged into calculations, but at $0); failing to ensure appropriate and complete documentation; and assuming computer systems work without careful checks and confirmation.

Focus on “Getting it Right”

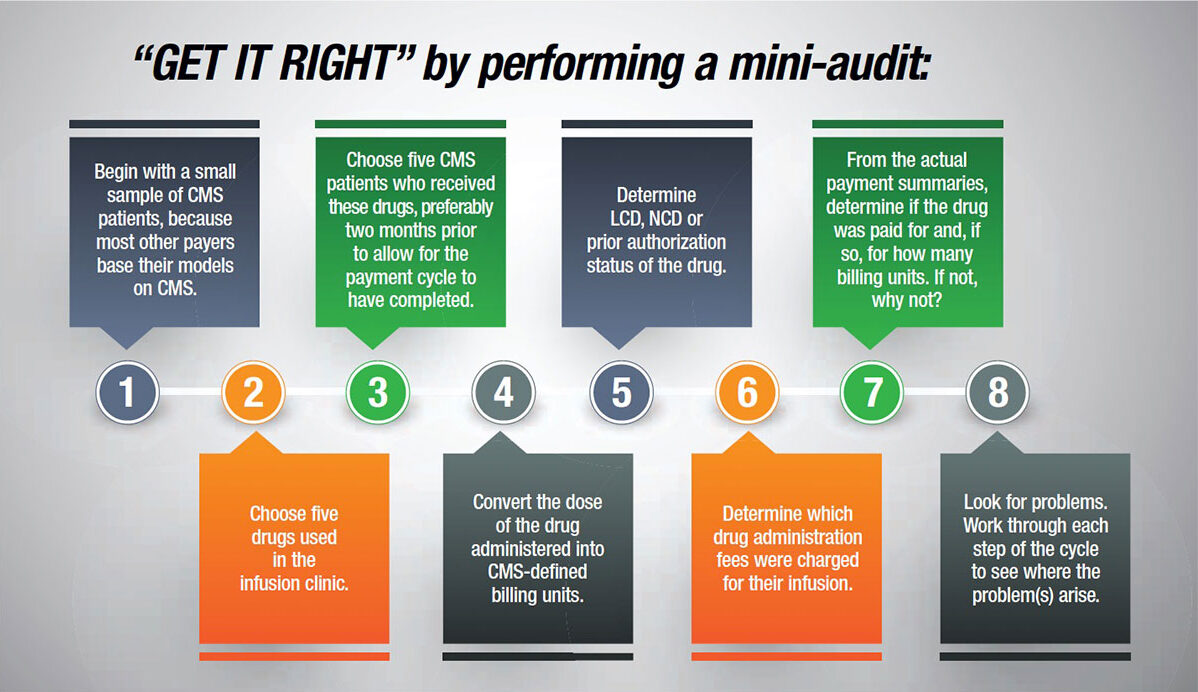

Hospital and healthcare facilities have revenue cycle teams, groups of financial executives and an IT infrastructure, all of which are tasked with ensuring appropriate and correct reimbursement. While these services may be outsourced, the responsibility still lies with the practice site. Therefore, getting it right starts with using the correct ICD-9/ICD-10 codes to identify the conditions the patient is being treated for. Since payment for drugs is often restricted to labelled indications, specific use in specific disease states or as part of a defined treatment pathway, it’s essential that this data is transmitted to the payer. Next come prior authorizations, LCDs and NCDs. If the payer has requirements for use, providers need to meet these and document them in a manner that is codable to be transmitted to the payer.

Billing for the drug itself depends on using the correct healthcare common procedure coding system code (some of which are brand-specific, including those for immune globulin products) and correctly converting the actual dose administered into the number of CMS-defined and -assigned billing units. These are specific to each drug, and Medicare and most other payers require converting the dose of the drug given into billing units that are then submitted for billing. Providers are not paid for the entire vial — only for the amount used for that patient. But, they can bill for waste if the product purchased in a single dose vial has been used for a Medicare patient. Medicare makes a provision for billing for waste; most other payers don’t. If a temporary miscellaneous code for a new drug is used, an NDC code is needed. That code is the only thing that will actually identify which drug was used.

It is essential to ensure that this conversion is working correctly through all steps — from the drug being entered into the pharmacy computer system to the bill being released. There are a lot of places this can go awry and leave providers billing for only a fraction of what they should be. Billing unit errors are one of the major issues reported by Medicare, which convey the false impression that a specific disease state can be treated with a much lower dose than is actually the case.

Lastly, drug administration plays a major role. It is designed to cover the costs of the use of local anesthesia; starting the IV; access to IV, catheter or port; routine tubing, syringe and supplies; preparation of the drug; flushing at completion; and hydration fluid. Each of the biologic, immunologic and chemotherapy agents administered in the infusion center qualifies for the upper-level drug administration fees, a portion of which should be transferred back to the pharmacy cost center.

Editor’s Note: The content of this column is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.