Adult Vaccines: A Needed Boost

With suboptimal vaccination rates among adults to protect against preventable diseases, steps are being taken to heighten awareness and increase access to adult vaccines.

- By Ronale Tucker Rhodes, MS

EACH YEAR, THERE are countless media reports surrounding the debate about childhood vaccination rates. Yet, little attention is paid to the exceedingly low adult vaccination rates. This should be alarming since only 300 U.S. children die each year from vaccine-preventable diseases, compared with approximately 42,000 U.S. adults.1 Indeed, more adults die from vaccine-preventable diseases than from breast cancer, HIV/AIDS or traffic accidents.2

The reasons behind these low vaccination rates vary from lack of patient education and/or perceived value to inadequate recommendations from healthcare providers and insurance reimbursement. But, there do exist very clear recommended vaccine guidelines by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for adults young and old, as well as those who are pregnant and have health conditions. As such, to increase vaccination rates, programs and campaigns are being implemented to promote the importance of vaccination throughout the lifespan.

Assessing the Numbers

In 2016, CDC published a report that looked at the lifetime use of seven common vaccines — influenza, pneumococcal, tetanus toxoid-containing (tetanus and diphtheria [Td] or tetanus and diphtheria with acellular pertussis [Tdap]), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, herpes zoster [shingles] and human papillomavirus [HPV]) — among adults in 2014, three of which — pneumococcal disease, shingles and hepatitis B — have goals in its Healthy People 2020 documents. According to the report, compared with 2013, only modest increases occurred in Tdap vaccination among adults older than 19 years and herpes zoster vaccination among adults older than 60 years. Coverage among adults for all other vaccines didn’t improve at all.

Specifically, the report showed that influenza vaccination coverage among adults older than 19 years was 43.2 percent; pneumococcal vaccination among high-risk persons aged 19 through 64 years was 20.3 percent and among adults older than 65 years was 61.3 percent; Td, hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination coverage among adults older than 19 years was 62.2 percent, 9 percent and 24.5 percent, respectively; HPV vaccination coverage among adults 19 through 26 years was 40.2 percent for females and 8.2 percent for males; and herpes zoster vaccination coverage among adults older than 60 was 27.9 percent. CDC’s goal is to have 90 percent of adults immunized with the pneumococcal and hepatitis vaccines and 30 percent of adults over age 60 immunized with the herpes zoster vaccine by 2020.

Why are the numbers so low? Interestingly, CDC’s report showed that having health insurance coverage and a usual place for healthcare(regardless if they have health insurance) are associated with higher vaccination coverage, but those factors don’t ensure optimal coverage. For instance, even among adults who had health insurance and more than 10 physician contacts within 2014, between 23.8 percent and 88.8 percent (depending on the vaccine and age) reported not having received vaccinations that were recommended.3

Robert Wergin, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, says lack of patient education is one cause of low vaccination rates among adults. “Many adults don’t know what vaccines they should have,” said Dr. Wergin. This is because unlike children, adults don’t have regular well-child visits where they get vaccinated. And, while public health officials say doctors need to recommend vaccines more often when they see patients, Carolyn Bridges, MD, associate director for adult immunization at CDC, says, “Primary care doctors think vaccines are important, but it’s difficult for them to incorporate vaccination into giving routine care.”4

According to a policy researcher at RAND Corp., adults may not see the consequences of not getting a vaccine.5 In a RAND survey of adults who went unvaccinated for the flu in the 2009-2010 season, more than half cited factors relating to a perceived lack of value as their main reason. Reasons included a lack of perceived need (28 percent), lack of belief in flu vaccines (14 percent) and a perceived risk of illness or side effects (14 percent). In another RAND study, an analysis of data from 2008 calculated missed opportunities based on vaccination and care use data, and found that more than 53 million U.S. adults had at least one healthcare provider contact between October and December but remained unvaccinated. According to the study, if all of those patients had been vaccinated, it would have increased overall vaccination by about 23 percent. Yet, the analysis also found that if only those unvaccinated adults who were willing to be vaccinated were counted, the gains would be an increase of only about 14 percent, suggesting that resistance to vaccination plays a significant role.6

A survey conducted by researchers from the University of Colorado School of Medicine in collaboration with CDC in 2014 identified the following barriers to the delivery of adult vaccines: failure of healthcare providers to assess vaccination needs of patients, insufficient stock of vaccines, inadequate insurance reimbursement, record-keeping challenges and high costs. The survey was answered by 79 percent of general internists and 62 percent of family physicians surveyed from March 2012 through June 2012 in the U.S. Almost all physicians reported assessing patients’ vaccination status at annual visits or first visits, but only 29 percent of general internists and 32 percent of family physicians reported doing so at every visit. The survey also found that most physicians aren’t stocking all recommended vaccines, with money cited as the top reason.7 For instance, physicians often don’t store the shingles vaccine in their office because it has a limited shelf life, and billing private Medicare prescription drug insurers is complex. So, doctors often issue a prescription for the shot for the patient to fill it at a pharmacy or health clinic, which is an extra step that deters some people.4 In addition, the most commonly reported reasons for referring patients elsewhere such as pharmacies, retail stores and public health departments for vaccines were insurance coverage for the vaccine (36 percent) or inadequate reimbursement (41 percent).7 While the Affordable Care Act requires private insurers to pay 100 percent for all preventive services, including vaccines, that is not so for Medicare. Flu and pneumonia vaccines are free Under Medicare Part B, but vaccinations for shingles and tetanus are covered under Medicare Part D and often require co-payments of $100 or more.4

Adult Vaccine Recommendations

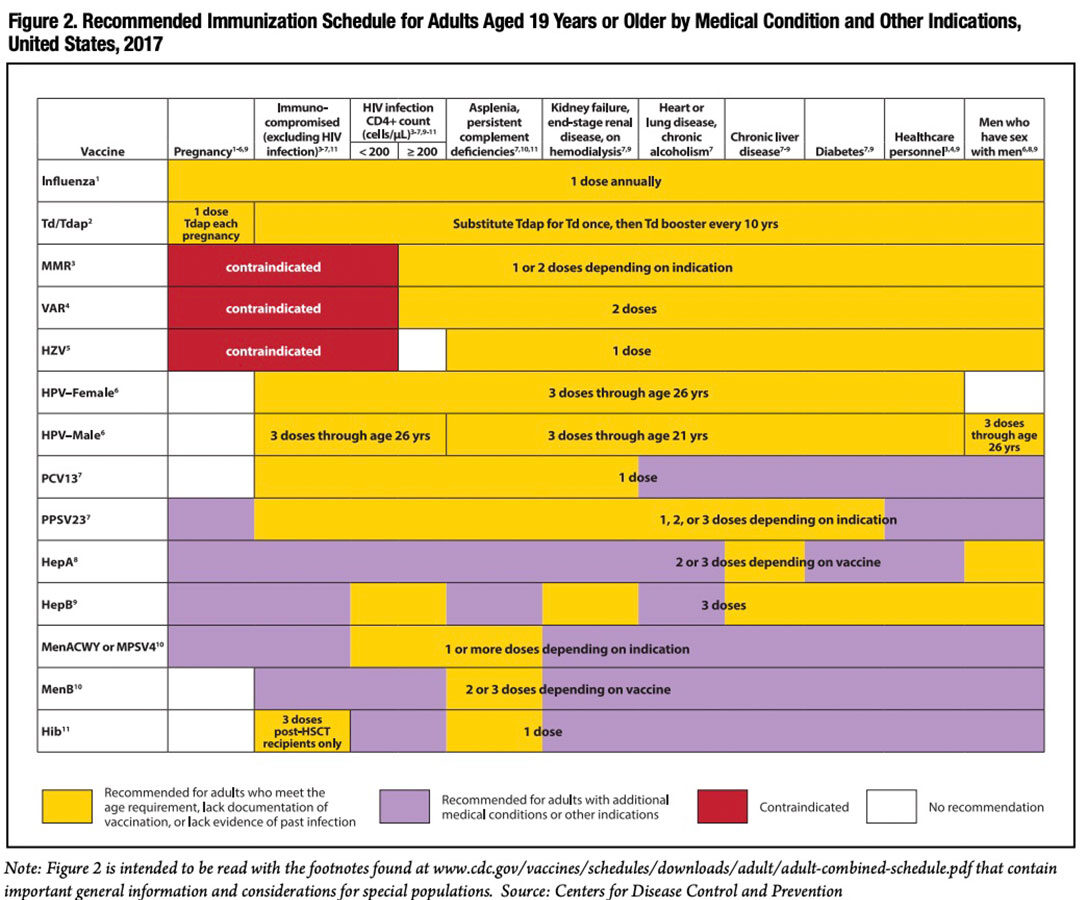

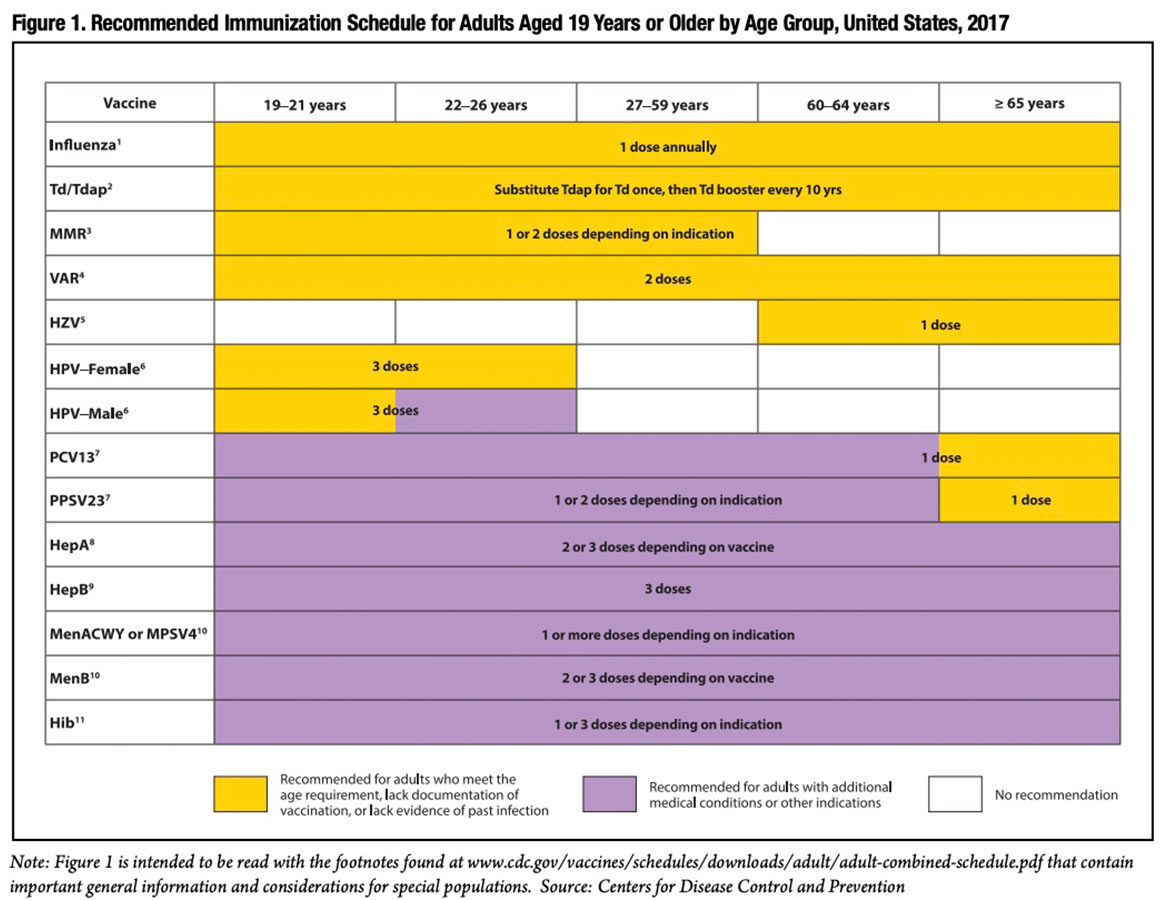

Each year, CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) releases its recommended schedule of vaccinations for all adults. Vaccinations are recommended for specific populations based on a person’s age, health conditions, behavioral risk factors, occupation, travel and other indications (Figures 1 and 2).8

All adults. ACIP recommends all adults get the annual flu shot every year. It also recommends that all adults get the Tdap vaccine if they did not receive it as a child, and then a Td booster shot every 10 years.

Adults 19 through 26 years old. Young adults should receive the HPV vaccine to protect against the human papilloma viruses that cause most cervical and anal cancers and anal warts. The HPV vaccine is recommended for women up to age 26 years, men up to age 21 years and men ages 22 to 26 years who have sex with other men.

Adults 60 years and older. The zoster vaccine that protects against shingles is recommended for adults 60 and older. ACIP recommends the pneumococcal vaccine that protects against pneumococcal disease, including infections in the lungs and bloodstream, for all adults over 65, and for adults younger than 65 who have chronic health conditions.

Adults with health conditions. While no specific vaccines are recommended for adults with health conditions other than the seasonal flu vaccine and the Tdap or Td vaccine, ACIP does recommend individuals speak with their doctor if they have asplenia; diabetes types 1 or 2; heart disease, stroke or other cardiovascular disease; HIV infection; liver disease; renal disease; or a weakened immune system.

Pregnant women. Women who are pregnant should receive a Tdap vaccine between 27 and 36 weeks of pregnancy (preferably during the earlier part) to help protect against whooping cough. They are also recommended to receive a flu shot during flu season, which is October through May.

Healthcare workers. Because of the risk of exposure to serious diseases, healthcare workers should receive the hepatitis B vaccine, the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine if they were born in 1957 or later and have not had the MMR vaccine, and the varicella (chickenpox) vaccine if they have not had chickenpox. If they don’t have documented evidence of a complete hepB vaccine series or an up-to-date blood test that shows them immune to hepatitis, MMR or varicella, they should receive the full-dose series of the vaccines. In addition, those who are routinely exposed to isolates of N. meningitidis should get one dose of the meningococcal vaccine.

ACIP also makes recommendations for international travelers and immigrants/refugees, as well as recommendations for those who should not be vaccinated against certain diseases, which can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/index.html.

Taking Steps to Turn the Tide

In response to survey results, RAND Corp. researchers suggest many strategies for boosting vaccination rates. One way is to step up conventional strategies, including mail/telephone reminders and physician recommendations and offering vaccines at more convenient locations. Another is to make special efforts to reach out to healthy young adults who do not visit providers often and are difficult to reach. These efforts could include using new media to deliver public service announcements and making vaccines available at work. And, for those who are skeptical about vaccines, they suggest one-on-one counseling with healthcare providers to help them understand that vaccination poses little risk compared to the risk of going unvaccinated both for themselves and those around them.6

Efforts are being made at a grassroots level to improve vaccination rates. Some examples include clinics and hospitals offering drive-through flu shots that are given to people in their cars; the Uber ride-sharing service letting customers use their cell phone app to get free flu shots in Washington, Boston and New York; some health systems using their electronic medical records to identify seniors who need vaccines and then advising physicians to call them; and health systems giving bigger roles to nurses and medical assistants by allowing them to review patients’ records and offer vaccines without interrupting physicians.4

A good example of a grassroots initiative was launched by Duke University in Durham, N.C., in 2016. Titled the Adult Immunization Project, it focuses on working with providers throughout the Duke Health System. According to Tracy Y. Wang, MD, MHS, MSc, associate professor at Duke University, researchers analyze educational interventions used in primary care practices throughout the Duke system to try to understand which are successful and why. The data are then fed into an analytics platform where healthcare providers are able to view a patient’s vaccination status, identify high-risk patients and connect patients with targeted interventions.9

In addition, many state and federal organizations have come up with programs and campaigns to address the issue. At the state level, for example, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services launched the Start the Conversation campaign designed to promote a two-way conversation between healthcare providers and patients, stressing the importance of vaccination through the lifespan. Included in the campaign is a toolkit with resources for the entire healthcare team, including nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians, physician assistants, practice managers, clinical managers and administrative staff.10

At the federal level, the National Vaccine Advisory Committee launched the National Adult Immunization Plan (NAIP) in 2015 that “is intended to facilitate coordinated action by federal and nonfederal partners to protect public health and achieve optimal prevention of infectious diseases and their consequences through vaccination of adults.” The NAIP establishes four key goals, each of which is supported by objectives and strategies to guide implementation through 2020:11

- Strengthen the adult immunization infrastructure;

- Improve access to adult vaccines;

- Increase community demand for adult immunizations; and

- Foster innovation in adult vaccine development and vaccination-related technologies.

In addition, the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases has created a national Campaign for Adult Immunization. In partnership with leading experts and organizations on adult vaccination, the campaign’s goals are to close the funding gap, support an Immunization Congressional Caucus and ensure all adults are fully aware of and have access to appropriate immunizations.12

Protection Is Needed Now

Vaccines are just as important for adults as they are for children to prevent getting and spreading diseases. With a disproportionate number of adults dying from vaccine-preventable diseases when compared to the experience of children, there is a pressing need to address the causes behind the abysmally low adult vaccination rates. It is hoped that some of the strategies put into place at both the grassroots and government levels will help to convince individuals of the need for these lifesaving vaccinations and doctors of the importance of doing their part to ensure adult patients are protected too.

References

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Immunization and Infectious Diseases. Accessed at www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases.

- National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Campaign for Adult Immunization. Accessed at www.adultvaccination.org/cai.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination Coverage Among Adults, Excluding Influenza Vaccination — United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Feb. 6, 2016. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6501a1.htm.

- Galewitz P. Vaccination Rates for Older Adults Falling Short. PBS Newshour, Sept. 16, 2015. Accessed at www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/vaccination-rates-older-adults-falling-short.

- Nuseibeh N. A Huge Number of American Adults Skip Vaccination, Study Finds, In Spite of Risks. Bustle, Feb. 8, 2014. Accessed at www.bustle.com/articles/15026-a-huge-number-of-american-adults-skip-vaccination-study-finds-in-spite-of-risks.

- Harris KM, Maurer J, Uscher-Pines L, et al. Seasonal Flu Vaccination: Why Don’t More Americans Get It? RAND Corp. Research Briefs, 2011. Accessed at www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9572.html.

- Scutti S. Why Are Vaccination Rates So Low? 30,000 Adults Die Each Year of Vaccine PreventableIllnesses. Medical Daily, Feb. 5, 2014. Accessed at www.medicaldaily.com/why-are-vaccination-rates-so-low-30000-adults-die-each-year-vaccine-preventable-illnesses-268698.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Vaccines Are Recommended for You? Accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/index.html.

- Zimlich R. Duke Launches Campaign to Boost Adult Vaccination. Medical Economics, Dec. 13, 2016. Accessed at medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/news/duke-launches-campaign-boost-adult-vaccination.

- New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. Adult Immunization Campaign. Accessed at www.dhhs.nh.gov/dphs/immunization/campaign.htm.

- National Vaccine Program Office. National Adult Immunization Plan, Feb. 5, 2015. Accessed at www.scribd.com/document/279462029/National-Adult-Immunization-Plan-Draft.

- National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Campaign for Adult Immunization. Accessed at www.adultvaccination.org/cai.