Blood Protein Therapeutics: It All Starts with the Plasma

- By Keith Berman, MPH, MBA

Maintaining a cadre of healthy donors is essential for manufacturing lifesaving plasma protein therapies. A donor’s good health is important to ensure safe and effective final therapies for patients, but it is also of paramount importance to protect the donor’s health.

— Mary Gustafson, vice president, global medical and regulatory policy, Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association

MOST ADULTS have learned at some point that blood is important because red blood cells carry oxygen to our vital organs and tissues, and white blood cells help fight infections. And thanks in part to growing appeals for platelet donors, some also appreciate that there is a specialized type of blood cell that stops bleeding. But far fewer lay people are aware that hundreds of proteins, performing important or life-critical functions, are constantly circulating in the straw-colored liquid plasma that comprises around 60 percent of human blood.

Today, a relative handful of these proteins are purified from donor human plasma and prescribed to treat persons with hereditary or other deficiencies: immune globulins that combat infectious diseases and regulate immunity, albumin responsible for maintaining blood pressure and a host of other functions, a number of clotting factors essential for normal hemostasis, alpha-1 antitrypsin that protects pulmonary elastic tissue against the destructive activity of the enzyme elastase.

The Growing Need for Plasma and Plasma Donors

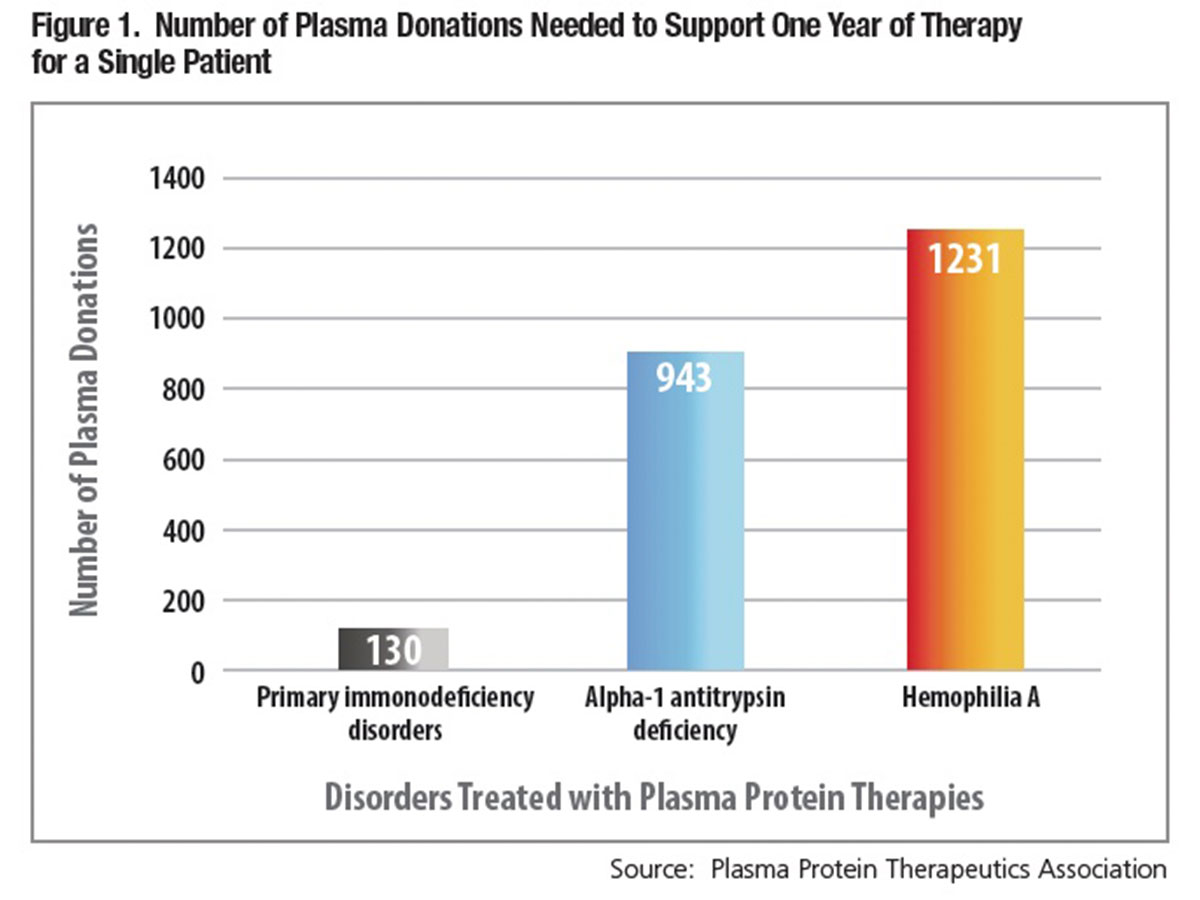

Beyond the fact that they are both sourced from human donors, a vast gulf separates the typical needs of a patient who requires red cell or platelet transfusions and one who requires most plasma protein therapies. As little as one or perhaps a few whole blood or apheresis donors can cover a single patient’s typically acute, short-term platelet or red cell transfusion requirements. But for individuals reliant on most plasma protein therapies, the formula is turned on its head: Treatment is frequently chronic or lifelong. Literally hundreds of individual plasma donations are required to purify enough treatment to meet the annual requirements of an adult who needs immune globulin, clotting factor or alpha-1 antitrypsin therapy (Figure 1).

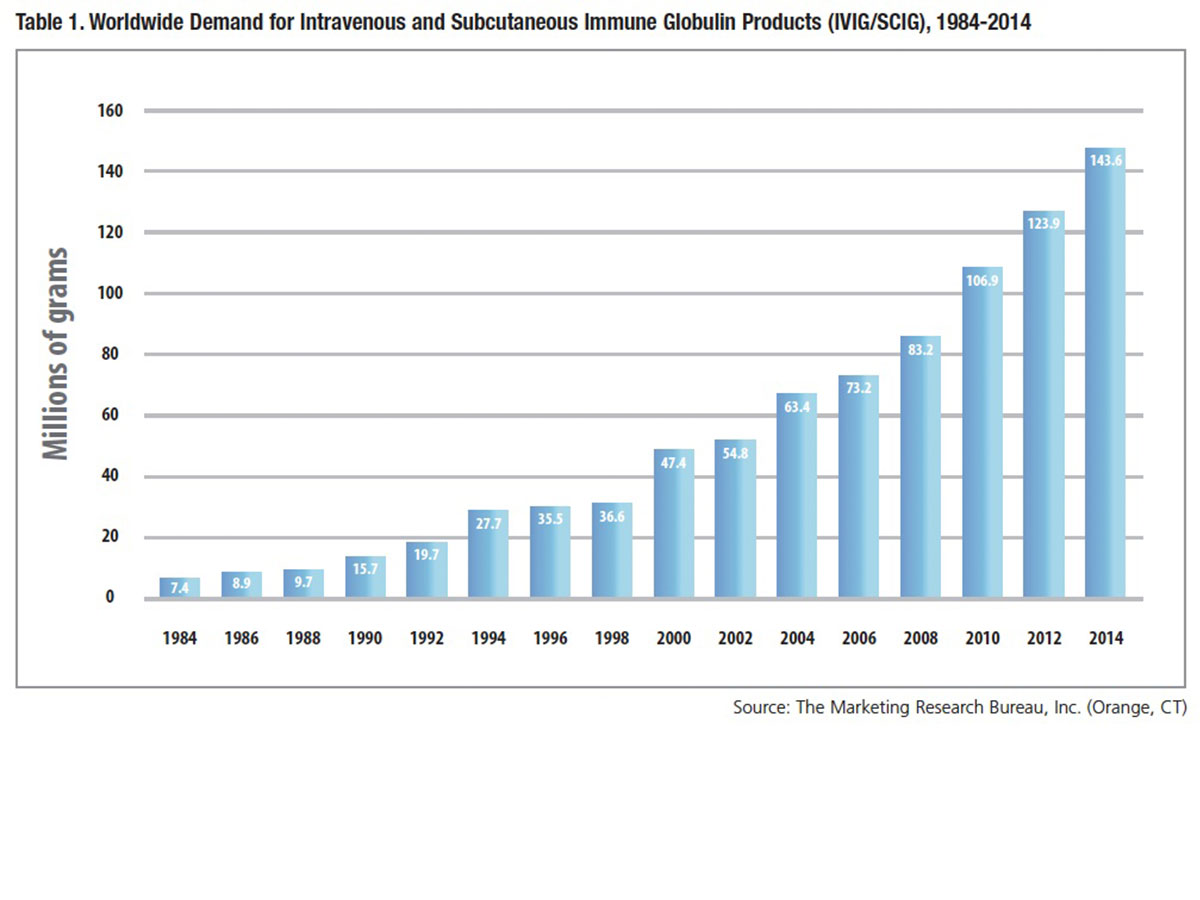

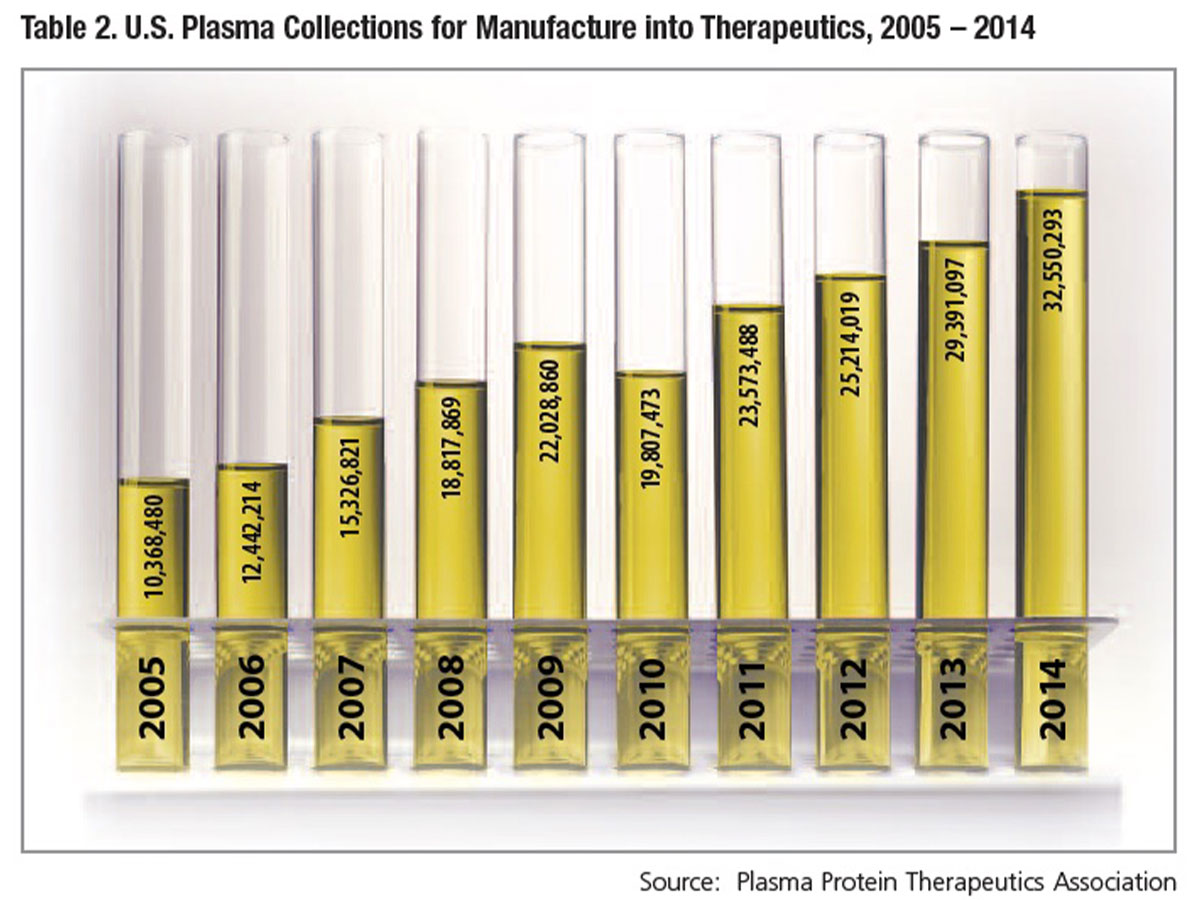

Coupled with the large number of plasma donations to treat a single patient is a growing U.S. and international patient market, as more people are diagnosed and prescribed treatment. Where once plasma donors were recruited in order to make enough albumin to meet hospital needs, demand for intravenous and subcutaneous IgG immune globulin (IVIG and SCIG) therapies now dictates the requirement for donated plasma — the result of 30 years of continuous growth in global usage (Table 1). Between 2000 and 2014, combined demand for IVIG and SCIG grew nearly 8 percent annually on average, necessitating a similar pace of recruitment of plasma donors and collections. Over the most recently reported 10-year period, U.S. plasma collections have increased nearly three-fold, from 10.4 million in 2005 to 32.5 million in 2014 (Table 2).

An automated plasmapheresis procedure is used to collect an average of about 750 mL of plasma* during a donation session that typically lasts one to one-and-a-half hours, for which donors are compensated for their time. All cellular components are returned to the donor, sometimes along with sterile saline to maintain blood volume. More than 480 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-licensed centers throughout the U.S. are engaged in plasma collection activity, according to the Marketing Research Bureau.

With this vast and ever-expanding plasma collection enterprise comes a two-fold responsibility for industry: 1) to assure the quality and safety of this critical raw material and 2) to safeguard the health of the plasma donor.

Ensuring High Plasma Quality

While both U.S., Canadian and European government authorities license and regulate all plasma collection activities, in the early 1990s, the industry resolved to go beyond those requirements by instituting additional rigorous standards for certification of plasma collection centers under the Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association’s International Quality Plasma Program (IQPP).

In addition to defining standards for collection center management that encompass the facility itself, quality assurance and personnel education and training, IQPP sets donor qualification, management and health standards. The following are among the key requirements to become a qualified donor:

- Potential donors must pass two separate medical screenings to assure that they are in good health.

- Donated plasma from potential donors is collected and tested on two different collection dates using highly sensitive assays for HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV); no plasma is released for processing or “fractionation” until testing results from the second donation come back nonreactive.

- If a first-time donor does not return to donate a second time within six months, that donor loses his/her qualified donor status and must qualify again; plasma from a one-time plasma donor — even when all test results are nonreactive — cannot be used to manufacture products.

- All new donors are checked against the National Donor Deferral Registry database, which includes persons permanently deferred from donating plasma at any IQPP–certified plasma collection center due to positive test results for HIV, HBV or HCV.

Additionally, an IQPP community-based donor standard only allows donors who permanently reside within the defined donor recruitment area of the plasma collection center to donate at that center. This standard has been shown to help maintain a steady and reliable donor population and supply of quality plasma.

In the 1980s, to assure that therapeutic plasma derivatives do not transmit viral or other infections, FDA regulators and industry implemented a “tripod” of safety measures: donor screening, pathogen testing and pathogen inactivation and removal steps during processing.1 The IQPP donor management standards have proven to be integral to the success of both the donor screening and pathogen testing elements of the safety “tripod.” Last year marked a very significant safety milestone for the plasma products industry and the patients it serves: Two decades and many millions of doses of IG, albumin, clotting factors and other licensed plasma-based therapeutics have been administered to U.S. patients without a single report of infection transmission.**

Protecting Plasma Donor Health

As it is for volunteer whole blood and apheresis platelet and red cell donors, a paramount priority is to ensure that the collection process does not in any way compromise the health of the plasma donor. Toward this end, federal regulations relating to donors of source plasma require:

- An appropriate medical history and examination of the donor by qualified medical staff, certifying that the donor is in good health.

- Temperature not to exceed 37.5 degrees Celsius (99.5 degrees Fahrenheit) and body weight equal or greater than 110 pounds on the day of the procedure.

- Systolic and diastolic blood pressures between 90 mmHg and 180 mmHg and 50 mmHg and 100 mmHg, respectively, with a regular pulse between 50 and 100 beats per minute.

- Hemoglobin greater than or equal to 13.0 gm/dL (39 percent hematocrit) in males and greater than 12.5 gm/dL (38 percent hematocrit) in females.

- Total plasma protein of no less than 6.0 grams per 100 mL of blood; the donor is deferred if total plasma protein drops below this standard, and can donate again only when it returns to an acceptable level.

Plasma collection center medical staff must defer any donor or prospective donor found to have a medical condition that would place the donor at risk from the plasmapheresis procedure. Plasma donors are weighed at each donation visit to accurately calculate the appropriate plasma volume to be collected based on a weight-specific nomogram. Plasma may be donated up to two times weekly, with a minimum of two days between donation visits. This allows adequate recovery of circulating plasma protein levels. Very infrequently, a plasma donor may misunderstand the reasons for limiting the number of times he or she can donate per week and attempt to “cross donate” more often than is allowed at a different plasma collection center. Measures in the IQPP Cross Donation Management Standard are in place to protect the health of the donor by minimizing the risk of cross donation.

The plasmapheresis procedure separates the donor’s plasma from whole blood using a sterile, pyrogen-free, single-use donor set and sterile, pyrogen-free anticoagulant solution. Blood is collected, the plasma separated and the cellular components returned to the donor using aseptic methods. All IQPP-certified centers have processes in place to monitor, manage and record any donor adverse events that might occur. Adverse events occur very infrequently, are usually minor and include vasovagal reactions (e.g., hypotension, lightheadedness and nausea), reactions to citrate used as an anticoagulant (e.g., perioral tingling and metallic taste), allergic reactions and itching or hematoma at the venipuncture site. Overall adverse event rates in donors giving plasma by apheresis are significantly lower than for whole blood donors and also appear to be lower than for donors giving platelets or white blood cells by apheresis.2,3

Other studies examining the safety of regular long-term plasma donation demonstrate that it is safe. Parameters of humoral and cellular immunity in plasma donors are normal and not different from nondonors. Similarly, there are no signs of iron store depletion or increased cardiovascular risk associated with long-term plasma donation.4

Donors Who Feel Well Come Back

Finally, there is mutual self-interest in assuring that a qualified donor stays in peak health and thus minimize risks of donation-related side effects. The donor who feels well after the procedure is one who is less likely to skip donation visits or entirely drop out. The plasma collection center benefits when it doesn’t have to recruit and qualify new replacement donors.

Thus, donors receive basic education about how to optimize their health, as well as specific tips to prepare for the donation visit. They are encouraged to eat healthy meals that include foods high in protein and iron, avoid smoking (or stop smoking 30 minutes prior to donation to avoid changes in heart rate and blood pressure that could result in a deferment), and get at least seven to nine hours of sleep. On the night before and the day of the plasmapheresis procedure, donors are reminded to drink plenty of water or juice to assure that the body is well-hydrated and reduce the risk of side effects, including lightheadedness. For the same reason, they are advised to avoid drinking alcoholic beverages, which can cause dehydration.

The plasma donor is the first vital part of the process to produce safe and effective plasma protein therapeutics. Fully aware of the need for even more donors tomorrow, next year and into the future, the industry can be counted on to make the safety and health of its plasma donors its first priority.

* Referred to as “source plasma.” According to the Marketing Research Bureau, source plasma accounted for nearly 95 percent of the total volume of plasma directed for further manufacture into plasma protein therapeutics in 2014; the balance was “recovered plasma” from whole blood donations.

** In 1995, a single production lot of a factor VIII concentrate was implicated in the infection of three hemophilia A patients (MMWR 1996 Jan 19;45[2]:29-32). The FDA is not aware of a definitive cause of that contamination event (personal communication, R. Chapelle, FDA/CBER).

References

- Berman K. Human plasma products: Two decades of unsurpassed safety. BioSupply Trends Quarterly 2012 Apr:52-6. Accessed at: www.bstquarterly.com/Assets/downloads/BSTQ/FullIssues/BSTQ_2012-04_Full-Issue.pdf.

- McLeod BC, Price TH, Owen H, et al. Frequency of immediate adverse effects associated with apheresis donation. Transfusion 1998 Oct;38(10):938-43.

- Winters J. Complications of donor apheresis. J Clin Apher 2006 Jul;21(2):132-41.

- Tran-Mi B, Storch H, Seidel K, et al. The impact of different intensities of regular donor plasmapheresis on humoral and cellular immunity, red cell and iron metabolism, and cardiovascular risk markers. Vox Sang 2004 Apr;86(3):189-97.