Childhood Vaccine Refulsal: The Bad Outcomes of Good Intentions

- By Keith Berman, MPH, MBA

It isn’t what we know that gives us trouble, it’s what we know that just ain’t so.

— Will Rogers

VACCINES INCLUDED IN the routine childhood immunization schedule are extremely safe. Serious side effects are quite rare. Yet, today, a small but growing minority of parents — swayed by misinformation about vaccine-related health dangers or motivated by political, philosophical or religious beliefs — are choosing not have their children immunized, leaving them unprotected against a host of vaccine-preventable infectious childhood diseases.

This phenomenon is not new. A century ago, when smallpox vaccine was first deployed by health departments throughout the country to battle common outbreaks of the deadly disease, ardent anti-vaccination activists distributed bogus accounts of victims allegedly disfigured or killed by smallpox vaccine, invoked religious objections to vaccination and railed against government intervention in private life. Some successfully lobbied state legislatures to block or repeal compulsory vaccination laws.1 Meanwhile, in just the first four years, public vaccination programs drove down the average annual number of reported U.S. smallpox cases and deaths more than 12- and 24-fold, respectively.2 By 1930, smallpox was eradicated in this country.

But the anti-vaccination zealots of that era did manage to have a short-term impact. By the 1920s, prior to the eradication of smallpox, their efforts left just 10 states with compulsory vaccination laws, while 32 others either did not or even prohibited such laws. A lookback study later determined that the disease case rate in the 32 states where people could secure exemptions from receiving a smallpox vaccine was 10-fold higher than in the 10 states with laws making vaccination compulsory during smallpox outbreaks.2 While obviously unintended, the actions and fallacies spread by anti-vaccination advocates of that era accounted for many preventable smallpox deaths.

The Modern-Day “Anti-Vaxxer” Movement

If history does not exactly repeat itself, it certainly rhymes. Motivated by beliefs echoing those that drove the opponents of smallpox vaccination a century ago, the emergence of today’s generation of “anti-vaxxers” has coincided with significant declines in childhood vaccination rates in some communities. Anti-vaxxers disseminate and share misinformation about vaccine safety across the Internet, often taking form in heart-rending stories and personal testimonials posted on parenting blogs and discussion forums.3

All of this, of course, plays on the emotions of parents. Findings from a 2010 national survey of 376 households with children aged 6 years and younger revealed a surprising undercurrent of worry: 30 percent of parents reported concern that vaccines may cause learning disabilities such as autism, and about 35 percent said they believed their child was receiving too many vaccines in a single visit or in the first two years of life. Just 23 percent of parents reported no concerns about vaccine safety.4

But a comprehensive new literature review published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) offers some powerful new insights into the unique vulnerability of unvaccinated children, and how these unprotected children, in turn, act as the fuel that feeds disease outbreaks and epidemics.5 These insights may be helpful in bridging the understanding gap, both for parents and for state legislators considering bills to restrict or eliminate nonmedical vaccine opt-out exemptions.

Measles: Connecting Vaccine Exemption and Disease Risk

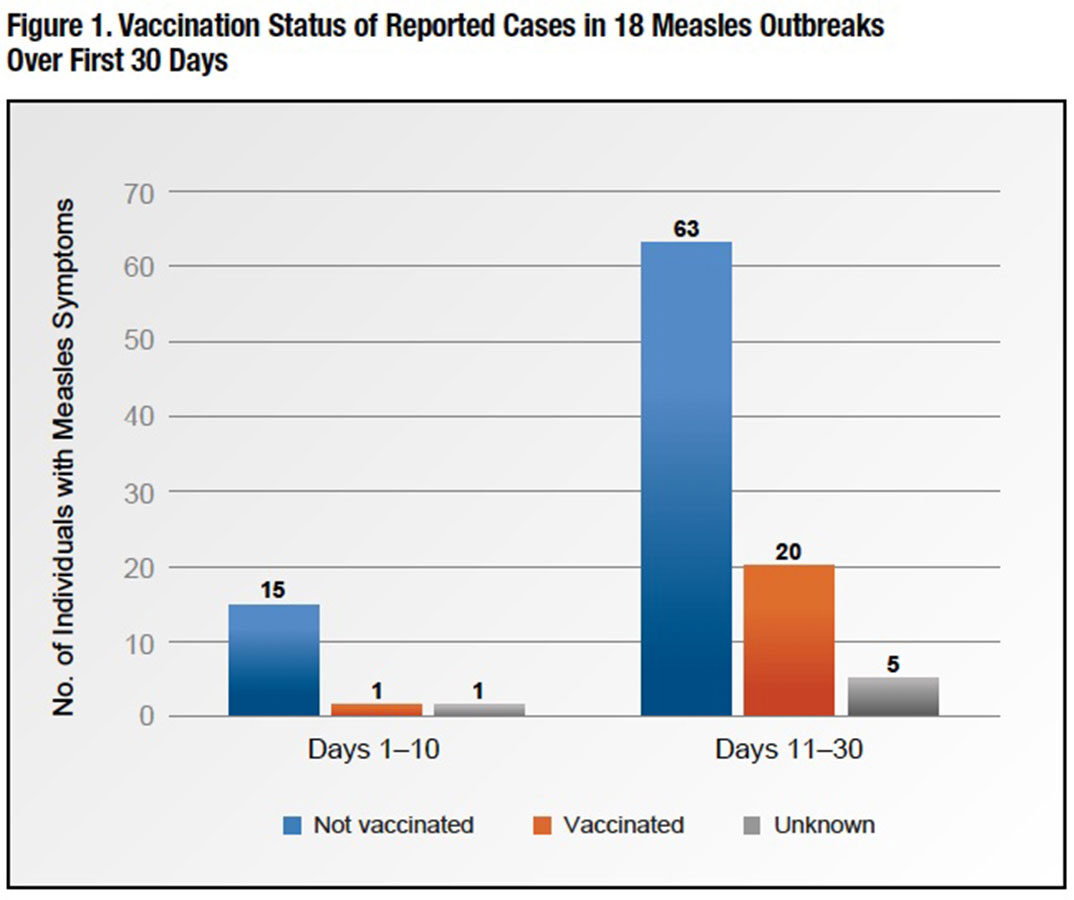

The JAMA authors identified 18 small measles outbreaks between 2000 and 2015, consisting of 145 cases, with sufficient information about vaccination status and symptom onset to construct a cumulative epidemic curve (Figure 1). Over outbreak days one through 10, 15 of the 17 earliest-generation measles cases were unvaccinated (one had received at least one dose of measles vaccine, and one had unknown vaccination status). From day 11 through day 30, 63 of 83 measles cases with known vaccination status — more than 75 percent — were also unvaccinated.

In a society where the vast majority of children and adults are immunized with measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, unvaccinated individuals are clearly critical to sustain measles transmission; without them, it is unclear how an outbreak could start or sustain itself.

Just how much higher is the risk that an unvaccinated child will contract measles during an outbreak? The JAMA authors cited national measles surveillance data reported to the CDC from 1985 through 1992, a period that included a 1989-1992 measles resurgence.6 What they found should be shared with every parent seriously considering opting out: Children who had a vaccine exemption were 35 times more likely to contract measles than vaccinated children. Unsurprisingly, additional data analysis revealed two important patterns:

1) High local aggregation — clustering — of individuals with exemptions is associated with greater measles incidence; and

2) Increased prevalence of vaccine exemptions in a geographic region is associated with higher disease risk in the nonexempt vaccinated population in that region.

Pertussis: Interplay of Vaccine Refusal and Waning Post-DTaP Immunity

Unlike measles, pertussis has remained endemic in the U.S. The introduction of whole-cell vaccine in the 1940s eventually reduced the incidence of this highly contagious bacterial disease, also known as whooping cough, to a nadir of just more than 1,000 cases in 1976. There has been a major resurgence of the disease over that last decade, which can cause serious and even life-threatening illness, particularly in infants. The largest recent epidemics included 9,154 cases in 2010 and 9,935 cases in 2014. An average of more than 31,000 cases were reported over the five-year period from 2010 through 2014, including an astonishing 48,277 cases of pertussis in the peak year of 2012.7

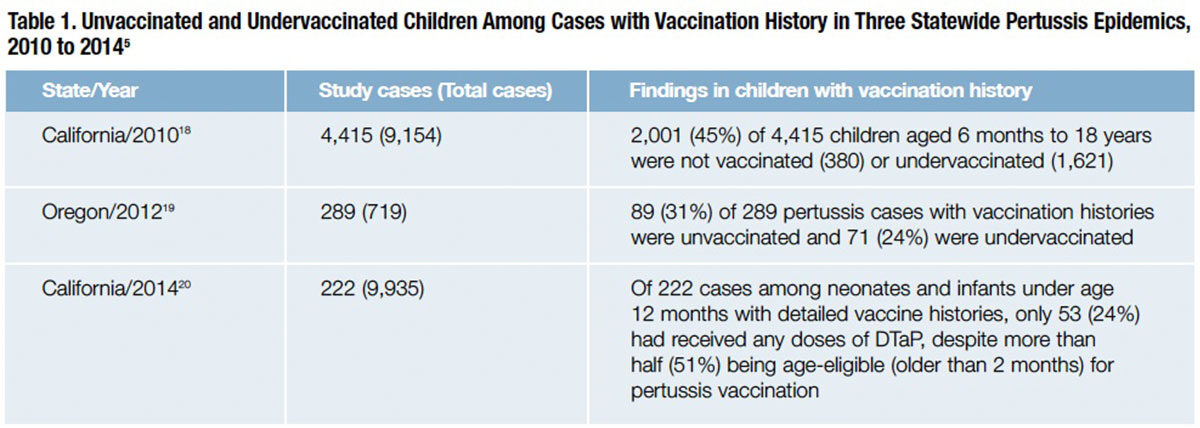

One factor contributing to this resurgence of pertussis is a problem of waning immunity to acellular pertussis vaccines introduced in the mid-1990s, which are less reactogenic than the whole-cell vaccine but also less durably protective. A recent meta-analysis of long-term immunity to pertussis after three or five doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTaP) vaccine determined that the odds of contracting pertussis increases by 1.33 times for each additional year after the last dose of vaccine.8 But atop this, the JAMA review documented the interplay of vaccine refusal in pertussis susceptibility: Across multiple reported statewide pertussis epidemics, unvaccinated or under-vaccinated children comprised a very substantial share of reported cases (Table 1).

Much like the measles risk data for unvaccinated children, a large case-control study analyzing pertussis cases from 1996 through 2007 found a nearly 20-fold increased risk of contracting the disease among individuals with vaccine refusal exemptions.9 A separate large case-control study affirmed that the risk of contracting pertussis is proportional to the number of missed doses of DTaP.10

These and other studies provide irrefutable evidence that childhood vaccine refusal for nonmedical reasons can cause harm in multiple ways:

• As the percentage of unvaccinated or undervaccinated children increases, so do the size and spread of disease outbreaks when an infected child arrives in the community;

• Unvaccinated and undervaccinated children place everyone else, and in particular medically exempt unvaccinated individuals, at increased risk of becoming infected during disease outbreaks; and

• The unvaccinated or undervaccinated child has a substantially greater risk of contracting the disease in the event of an outbreak compared to vaccinated children in the community.

States Move to Restrict Vaccination Exemptions

Sobering information of this nature can help providers educate resistant parents about the serious health risks that vaccine refusal creates for their child and the larger community. However, evidence from recent clinical trials suggests that even alarming messages about vaccine-preventable diseases and reassurance about the safety and societal benefits of vaccines may not be sufficient to convince many hesitant parents to vaccinate their children.11,12

Noting the proportion of parents claiming nonmedical exemptions from school immunization requirements and the association of vaccine refusal with disease outbreaks, public health experts are calling for restriction or elimination of nonmedical vaccine exemptions.13,14 Following a much-publicized measles outbreak in December 2014 that started at the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, Calif., the state’s legislature passed a bill last year that eliminates personal and religious belief exemptions, and requires all children attending public and private schools to be vaccinated.15

Since the new California law went into effect on July 1 of this year, just three vaccine exemptions remain in California: medical, special education and home schooling or independent study. Now, private or public childcare centers, preschools, elementary schools and secondary schools cannot admit children unless they are immunized against 10 diseases: diphtheria, Haemophilis influenza type b (bacterial meningitis), measles, mumps, pertussis, polio, rubella, tetanus, hepatitis B and varicella (chickenpox).

“There is persuasive evidence that stringent vaccination mandates reduce the risk of vaccine-preventable illness,” Stanford health law experts wrote in a New England Journal of Medicine commentary after the law’s passage. “Less clear is the effect California’s move will have on the politics of vaccination.”16 In fact, nearly all states (except California, Minnesota, Mississippi and West Virginia) continue to allow religious exemptions, and 17 states allow both religious and personal exemptions.17 Of the 11 states in which legislation was introduced in 2015 to remove personal belief, philosophical or religious exemptions, only California passed a bill that solely retains the medical exemption. Vermont removed only the philosophical exemption. The other nine states rejected the removal of any nonmedical exemption.

It is anybody’s guess whether or when the political climate will ultimately evolve to prompt other states to do away with nonmedical vaccine exemptions. Likelier than not, it will take even more disease outbreaks — accompanied by their toll in hospitalizations and childhood deaths — to overcome the passionate opposition of well-meaning people in the anti-vaxxer movement.

References

- Colgrove J. Science in a democracy: the contested status of vaccination in the progressive era and the 1920s. Isis 2005;96:167-191.

- World Health Organization. Smallpox and Its Eradication. Chapter 8: The Incidence and Control of Smallpox Between 1900 and 1958. Accessed at www.zeropox.info/bigredbook/BigRed_Ch08.pdf.

- Kata A. Anti-vaccine activist, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm — An overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine 2012 May 28;30(25):3778-89.

- Kennedy A, LaVail K, Nowak G, et al. Confidence about vaccines in the United States: Understanding Parents’ Perceptions. Health Affairs 2011;30(6):1151-9.

- Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, et al. Association between vaccine refusal and vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States: A review of measles and pertussis. JAMA 2016 Mar 15;315(11)1149-58.

- Salmon DA, Haer M, Gangarosa EJ, et al. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws. JAMA 1999;282(1):47-53.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis Cases by Year (1922-2014). Accessed at www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting/cases-by-year.html.

- McGirr A and Fisman DN. Duration of pertussis immunity after DTaP immunization: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015 Feb;135(2):331-43.

- Glanz JM, McClure DL, Magid DJ, et al. Parental refusal of pertussis vaccination is associated with an increased risk of pertussis infection in children. Pediatrics 2009;123(6):1446-51.

- Glanz JM, Narwaney KJ, Newcomer SR, et al. Association between undervaccination with diphtheria, tetanus toxoids, and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine and risk of pertussis infection in children 3 to 36 months of age. JAMA Pediatr 2013;1611(11):1060-4.

- Hendrix KS, Finnell SM, Zimet GD, et al. Vaccine message framing and parents’ intent to immunize their infants for MMR. Pediatrics 2014;134(3):e675-83.

- Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, et al. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2014;133(4):e835-42.

- Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine 2015 Nov 27;33 Suppl 4:D66-71.

- Davis MM. Toward high-reliability vaccination efforts in the United States. JAMA 2016 Mar 15;315(11):1115-7.

- California Legislative Information. SB-277 Public health: vaccinations. (2015-2016). Accessed at leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB277.

- Mello MM, Studdert DM, and Parmet WE. Shifting vaccination politics — The end of personal-belief exemptions in California. New Engl J Med 2015 Aug 27;373:785-7.

- Sandstrom A. Nearly all states allow religious exemptions for vaccination. Pew Research Center, July 16, 2015. Accessed at www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/07/16/nearly-all-states-allow-religious-exemptions-for-vaccinations.

- Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, et al. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr 2012 Dec;161(6):1091-6.

- Liko J, Robison SG, and Cieslak PR. Pertussis vaccine performance in an epidemic year — Oregon, 2012. Clin Infect Dis 2014;459(2):261-3.

- Winter K, Glaser C, Watt J, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Pertussis epidemic — California, 2014. MMWR 2014;63(48):1129-32.