Fibrin Sealants: When More Is Needed to Stop the Bleeding

- By Keith Berman, MPH, MBA

Fibrin sealant appears to be a significant adjunct to meticulous surgical technique, potentially providing faster, safer and more effective patient care.

— William D. Spotnitz, MD

SURGEONS RELY every day on sutures, staples, collagen pads, gelatin sponges and other simple hemostats to stop or control bleeding in the operating room. But sometimes these methods aren’t up to the task, or it takes too much time to achieve hemostasis. Depending on the procedure, difficult-to-control operative bleeding can cause a host of problems: prolonged operative time, impaired visualization of the surgical field, increased need for blood transfusions, increased re-operative risk and treatment failure.

Decades ago, the need was recognized for a material that could be topically applied to effectively stop or control bleeding, and in certain surgical settings — vascular anastomosis suture lines and dural graft placement, for example — to provide air and fluid tightness as well. The ideal product would need to be biocompatible and biodegradable, highly adhesive to various tissues, flexible yet possess adequate tensile strength and, very importantly, not induce inflammation, foreign body reactions, tissue necrosis or extensive fibrosis.1

At that time, it was recognized that the one product that could meet all of these criteria comes from ourselves: a concentrate of human fibrinogen and thrombin combined at the bleeding site directly or by spray applicator to both mimic and enhance the natural clotting cascade. Fibrin sealants were first conceptualized in the early 1940s,2,3 but early experimental agents prepared from plasma turned out to have suboptimal adhesive properties due to its naturally low fibrinogen level.4 A much higher fibrinogen concentration was needed for a fibrin-based biological adhesive to have the strength and tissue sealing properties required for difficult-to-control bleeds.

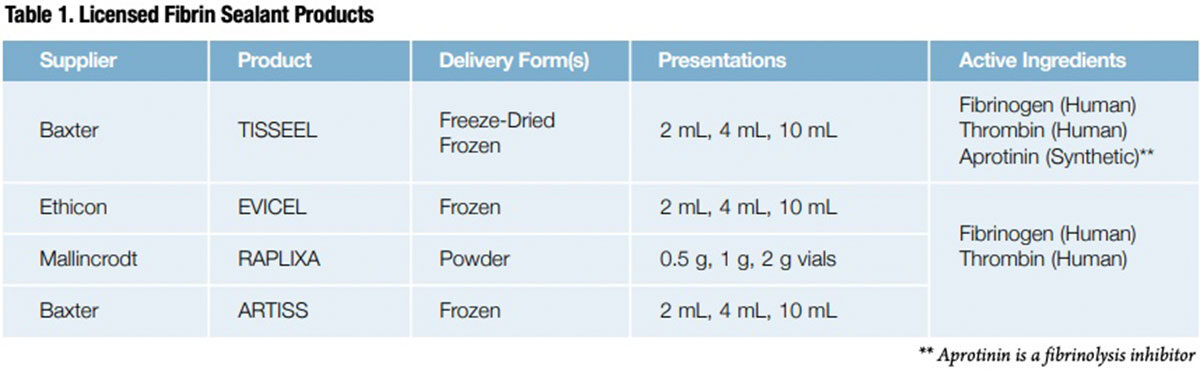

This technical barrier was finally solved as refinements to the original Cohn plasma fractionation process enabled manufacturers to highly concentrate specific plasma proteins, including fibrinogen and thrombin, on an industrial scale. In 1998, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Baxter’s TISSEEL, the first of four commercially available fibrin sealants that now include EVICEL (Ethicon), RAPLIXA (Mallincrodt) and ARTISS (Baxter), a novel slower-acting fibrin sealant (Table 1).

Fibrin Sealant Indications: From Narrow to Broad

Fibrin sealants — often referred to as “fibrin glue” in clinical literature — are used today in an extraordinary range of procedures, from diffuse mediastinal bleeding in cardiac surgery to bleeding from cut liver surfaces, adhesion of split thickness skin grafts, and oozing from vascular graft suture anastomoses. But to secure initial marketing approval from FDA and later expand the labeled indications for their products in these diverse surgical settings, manufacturers had to work through the inherent challenges of designing well-controlled, adequately powered patient trials for different types of surgeries, and defining appropriate clinical endpoints in each of them to document the benefits of fibrin sealants compared to conventional options to achieve hemostasis.

TISSEEL was first approved for use as an adjunct to hemostasis in cardiopulmonary bypass surgeries or for splenic injuries resulting from abdominal trauma, when control of bleeding by conventional techniques (e.g., suture, ligature, cautery) were ineffective or impractical.* EVICEL was initially licensed specifically for use in vascular surgery. But today, after FDA review of completed Phase III clinical studies across multiple surgical applications, these products, as well as RAPLIXA, are now broadly labeled for use as an adjunct to hemostasis when control of bleeding by standard techniques (such as suture, ligature or cautery) is ineffective or impractical.

However, the production of fibrin sealants is much more resource-intensive and complex than are conventional products used to control bleeding, and thus they are also more costly. Fibrinogen and thrombin are purified from screened donor plasma in highly controlled manufacturing processes, subjected to viral clearance steps, frozen, lyophilized or spray-dried, and delivered using an array of devices customized for different surgical applications. So while suture, pads, sponges and other conventional products used to control surgical bleeding can generally be used without restriction, fibrin sealants tend to be used more judiciously in the cost-conscious hospital operating room setting.

Uses and Clinical Benefits of Fibrin Sealants

Fortunately, in deciding when and in which types of surgeries it may be justified to use a fibrin sealant to manage hard-to-control bleeding, surgeons can refer to an extensive and growing body of published clinical experience. Below are findings from selected studies of some of the most common surgical applications of fibrin sealant products.

Bleeding anastomoses in vascular surgery procedures. In a single-blind Phase III trial, 175 adult patients undergoing vascular surgical procedures with suture hole bleeding were randomized to use of a fibrin sealant delivered with a gelatin sponge, or to the gelatin sponge alone. Procedures included arterial bypass (81 percent), arteriovenous graft formation (9 percent) and endarterectomy (9 percent). The mean time to hemostasis (TTH) was two minutes in the fibrin sealant arm versus four minutes in the control arm (P < 0.002). Similar reductions in TTH were also observed in patients receiving concomitant antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants or both.5

Fibrin sealant was evaluated in a Phase III randomized trial of fibrin sealant against gauze pads to control persistent anastomotic suture hole bleeding following placement of peripheral ePTFE vascular grafts, specifically arterio-arterial bypasses and arterio-venous shunts for dialysis access. In 44 of 70 patients (62.9 percent), a single application of fibrin sealant achieved suture line hemostasis within four minutes that was maintained until surgical closure, against 22 of 70 (31.4 percent) in the control patients (P < 0.0001).6

Mediastinal bleeding in cardiac surgeries. Diffuse mediastinal bleeding during open-heart surgery is exacerbated by multiple factors, including heparin anticoagulation and hypothermia. Difficult-to-control bleeding is especially problematic in reoperative cardiac surgery (“redo”) or emergency resternotomy. One large trial in this challenging surgical setting randomly assigned 333 patients to receive fibrin sealant or a conventional topical hemostatic agent when required during the operation.7 The success rate for fibrin sealant in controlling bleeding within five minutes of application was 92.6 percent, compared with only a 12.4 percent success rate with conventional topical agents (P < 0.001). Fibrin sealant also rapidly controlled 82 percent of bleeding episodes not initially controlled by conventional agents. Additionally, the emergency resternotomy rate following redo operations was significantly lower in the fibrin sealant group (5.6 percent) than in a non-matched historical control group (10 percent) (P < 0.0089).

Bleeding in liver resection surgery. Because the liver is highly vascular and the cut surface is friable, bleeding can be persistent and difficult to control despite the use of such conventional hemostatic techniques as heat cautery or argon beam coagulation. A number of serious postoperative complications are associated with prolonged bleeding in liver surgery.

A prospective trial randomized 121 undergoing hepatic resection to treatment with fibrin sealant administered by a spray applicator or standard topical hemostatic agents, used singly or in combination.8 The primary endpoint was time to hemostasis, and secondary outcomes included intraoperative blood loss and occurrence of complications, defined as reoperation for any reason, development of abdominal fluid collections, or bilious appearance of drained fluid for at least one day.

The mean time to hemostasis for the 116 evaluable patients was 282 seconds for the fibrin sealant group, compared with 468 seconds with standard agents (P = 0.06). While intraoperative blood loss was similar between the two groups, postoperatively, the percentage of patients with complications was 17.2 percent in the fibrin sealant group, about half the 36.5 percent complication rate in the control group (P = 0.02).

Bleeding in urological surgery. Bleeding control can be very difficult to achieve with conventional hemostats in partial or radical nephrectomy, prostatectomy and cystectomy. Investigators randomized 53 patients undergoing these and other urologic surgeries to use of EVICEL fibrin sealant or an absorbable hemostat. A significantly higher percentage of patients who received fibrin sealant achieved the primary endpoint of hemostasis at 10 minutes than those who received absorbable hemostat (96.4 percent [27/28] versus 72.0 percent [18/25]; relative risk [RR] = 1.34; P = 0.013). A lower overall incidence of treatment failure was also observed for patients who received fibrin sealant versus absorbable hemostat: 3.6 percent [1/28] versus 28.0 percent [7/25], respectively (RR = 0.13; P = 0.013).9

Fixation of skin grafts and skin flaps. Hematoma or seroma and poor graft adherence are frequent adverse outcomes with the use of sutures or staples to affix autologous skin grafts in burn patients, or skin flaps in cosmetic surgeries such as facelift or abdominoplasty. A number of comparative studies with commercial or single-donor fibrin sealants have documented various benefits compared to point fixation techniques, including reduced hematoma or seroma formation risk, reduced time to hemostasis, reduced transfusion requirements in patients with more extensive thermal injury and improved graft adherence with use of fibrin sealants compared to point fixation techniques.10,11,12,13,14

To allow surgeons more time to position the skin graft, Baxter developed ARTISS, a novel fibrin sealant whose human thrombin component is intentionally formulated at a very low concentration (2.5 to 6.5 IU/mL compared to 400 IU/mL or higher for other fibrin sealants). This product reformulation extends the fibrinogen polymerization time and gives the surgeon up to 60 seconds to manipulate and better position the graft or flap, while preserving the ability of this fibrin sealant to improve surface adherence to the wound bed and thus reduce “dead space” that results in increased risk of hematoma and seroma formation.

In a Phase III rhytidectomy study, a “split-face” design was used in each of 75 patients to evaluate flap adherence and reduction of dead space with ARTISS plus standard of care on one side and standard of care alone on the other side. Drainage volume in subjects treated with ARTISS was 7.7 ± 7.4 mL versus 20.0 ± 11.3 mL for the standard-of-care group (P < 0.0001). A total of seven hematoma or seroma events occurred in five subjects on the ARTISS side versus 17 hematomas/seromas in 17 patients on the standard-of-care side.15

Evidence, Experience and Usage Grow

Many years after the first products were introduced in the late 1990s, the need for fibrin sealants continues to increase. Between 2010 and 2015, demand by U.S. surgeons for fibrin sealant products climbed almost 50 percent, according to the Marketing Research Bureau.16 This impressive growth in usage shouldn’t come as a surprise. Hundreds of new studies — case reports, clinical trials and meta-analyses — were published over that same fiveyear period, adding to the thousands that preceded them. As more published evidence documenting their efficacy and safety accumulates, there is more interest in fibrin sealants as a standard option to achieve hemostasis or fluid-tight membranous sealing.

But, appropriately, surgeons tend to be conservative when considering significant changes to their standard practices. It can take time for an entirely new treatment approach to something as important as surgical hemostasis to be seriously considered, and more time for the surgeon to evaluate that new treatment in his or her own hands in the operating room. But in applications as diverse as head and neck surgery, hip and knee arthroplasty, mandibular third molar wound closure and anastomotic leakage following colorectal surgery, more surgeons each day discover for themselves the power of this potent concentrate of nature’s own solution to vascular bleeding.

* TISSEEL is also indicated as an adjunct in the closure of colostomies.

References

- Radosevich M, Goubran HA and Burnouf T. Fibrin sealant: scientific rationale, production methods, properties, and current clinical use. Vox Sang 1997;72:133-43.

- Young JZ, Medawar PB. Fibrin sutures of peripheral nerves: measurement of therate of regeneration. Lancet 1940;ii:126-8.

- Seddon HJ, Medawar PB. Fibrin sutures of human nerves. Lancet 1942;ii:87-92.

- Tidrick RT, Warner ED. Fibrin fixation of skin transplants. Surgery 1944;15:90-95.

- Gupta N, Chetter I,Hayes P, et al. Randomized trial of a dry-powder, fibrin sealant in vascular procedures. J Vasc Surg 2015 Nov;62(5):1288-95.

- Saha SP, Muluk S, Schenk W, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing fibrin sealant to manual compression for the treatment of anastomotic suture-hold bleeding in expanded polytetrafluoroethylene grafts. J Vasc Surg 2012 Jul;56(1):134-41.

- Rousou J, Levitsky S, Gonzelez-Lavin L,et al. Randomized clinical trial of fibrin sealant in patients undergoing resternotomy or reoperation after cardiac operations. A multicenter study. J thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989 Feb; 97(2):194-203.

- Schwartz M, Madariaga J, Hirose R, et al. Comparison of a new fibrin sealant with standard topical hemostatic agents. Arch Surg 2004 Nov;139(11):1148-54.

- Albala DM, Riebman JB, Kocharian R, et al. Hemostasis during urologic surgery: fibrin sealant compared with absorbable hemostat. Rev Urol 2015;17(1):25-30.

- Nervi C, Gamelli RL, Greenhalgh DG, et al. A multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the topical hemostatic efficacy of fibrin sealant in burn patients. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001 Mar-Apr;22(2):99-103.

- McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Lee M, et al. Use of fibrin sealant in thermal injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997 Sep-Oct;18(5):429-34.

- Stuart JD, Kenney JG, Lettieri J, et al. Application of single-donor fibrin glue to burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1988 Nov-Dec;9(6):619-22.

- Killion EA, Hyman CH, Hatef DA, et al. A systematic examination of the effect of tissue glues on rhytidectomy complications. Aesthet Surg J 2015 Mar;35(3):229-34.

- Lee JC, Teitelbaum J, Shajan JK, et al. The effect of fibrin sealant on the prevention of seroma formation after postbariatric abdominoplasty. Can J Plast Surg 2012 Fall;20(3):178-80.

- Hester TR, Shire JR, Nguyen DB, et al. Randomized, controlled, phase 3 study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of fibrin sealant VH S/D 4 s-apr (Artiss)to improve tissue adherence in subjects undergoing rhytidectomy. Aesthet Surg J 2013 May;33(4):487-96. 16. Personal communication with Patrick Robert (The Marketing Research Bureau, Inc., Orange, CT).