Immune Globulin: The Long and Short of It

Unpredictable fluctuation in supply and demand, combined with the current reimbursement model, is the root of the problem of affordableIG treatment.

- By Chris Ground

Immune globulin (IG) is a critical drug for tens of thousands of individuals in the U.S. who depend on it to treat a host of primary immune and autoimmune diseases. Without IG treatment — especially with the IG product that’s right for them — patients risk chronic debilitation, permanent physical damage and even death. That is why the availability of IG is so critical when it comes to patient care.

But availability is problematic because the IG supply and demand for it are continually fluctuating. Since its introduction in 1981, IG has gone through prolonged cycles of short supply followed by briefer periods of ample supply. When product supply fluctuates, price adjustments follow. And at times, this poses problems due to the current reimbursement model. When prices are at their highest, typically during short supply, the current reimbursement model fails to adequately compensate healthcare providers, leaving physicians little choice but to limit or stop treatment. Here’s why.

The Short Versus Long Market

The IG market is a classic supply and demand situation. When supply is low, it is called a short market, which means demand is higher than supply, resulting in increased prices. When there is ample supply, it is known as a long market, one where demand isn’t keeping pace with supply, typically resulting in decreased prices.

Why a market switches from short to long and back again is primarily a result of current and predicted demand (although historicially there have been a few other reasons). Over the years, the number of patients needing IG treatment has steadily increased. And the numbers multiply as doctors prescribe IG for off-indicated uses and research expands to determine the effectiveness of IG to treat other conditions.

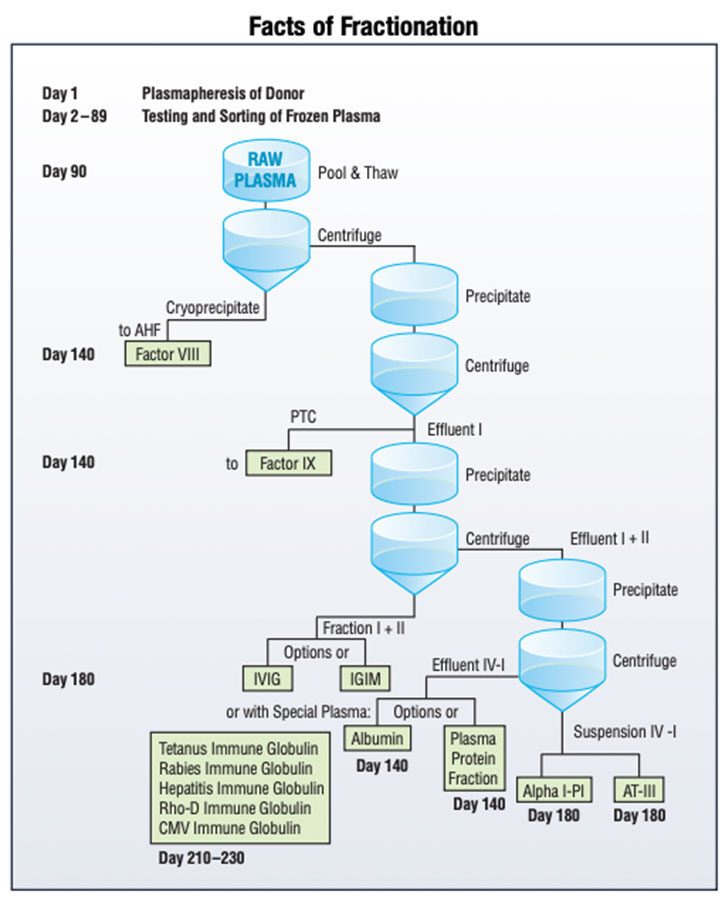

As demand increases, manufacturers ramp up production, unfortunately too much at times, which causes a long market. When this happens, manufacturers are forced to cool production until demand can catch up. For IG, though, it’s hard to predict just how much to cut back because plasma availability remains an uncertain limiting factor to increase supply levels (although this is changing as more plasma collection centers open in the U.S.). In addition, the IG manufacturing process, called fractionation, is lengthy, taking approximately seven to nine months from when an individual donates plasma to when the medication is ready for use. When demand does catch back up with supply, a short market returns.

The High Cost of IG

This may sound simple, but it is more complicated with IG. When compared to most other drug therapies, IG is high-cost, primarily because of the expense of plasma procurement, testing and fractionation. Fractionation — the months-long, arduous process of converting plasma into its three main commercial proteins: IG, factor and albumin (see Facts of Fractionation) — is only cost-effective if there is relatively equivalent demand for each of these products. When IG was first used to treat primary immune deficiency (PIDD) and autoimmune disorders (namely, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura or ITP), there was enough demand for each of the products. That changed when full-liter or total protein portfolio pull-through was reduced, caused first by the introduction of recombinant factor, which competed against fractionated plasma-derived factor, and followed by a decrease in albumin demand due to the release of a damaging and unfounded report. Without enough demand for factor and albumin, there was pressure to increase the cost of IG.

The High Cost of Low Reimbursement

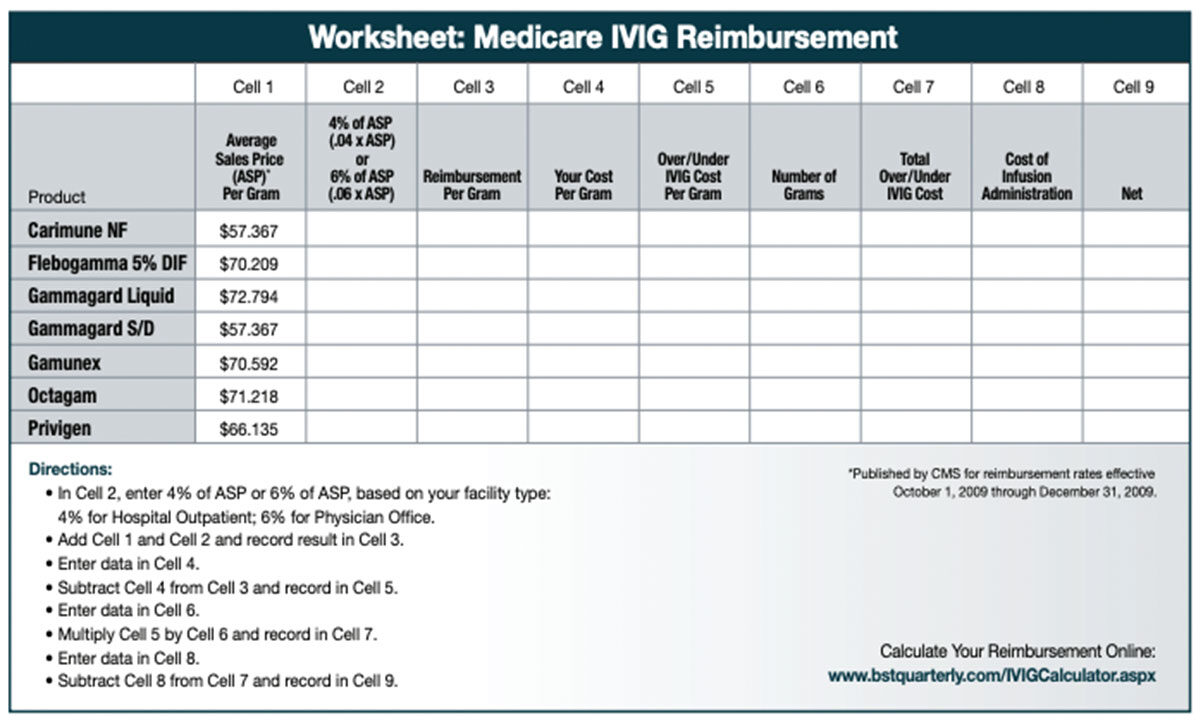

As IG costs increase, the reimbursement model for IG has become a problem for healthcare providers. In recent years, the reimbursement model, once based on average wholesale price (AWP), was changed to an average sales price (ASP) model. Although it was meant to apply mostly to Medicare reimbursement, private insurance companies are now beginning to follow Medicare’s lead to reduce their reimbursement costs.

Current Medicare reimbursement formulas are based on quarterly drug pricing data submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) by drug manufacturers, from which ASPs are calculated. Healthcare providers, then, are reimbursed the ASP plus a set percentage of ASP (currently, it is 4 percent for care given in hospital outpatient settings and 6 percent for treatment in physician offices). While the ASP rate changes each quarter, it is based on data from sales reports from the previous two quarters. That means the rate at which physicians are being reimbursed lags behind the economic realities of current prices. In a rising price environment brought on by a short market, healthcare providers often are paying more, sometimes substantially more, than the Medicare reimbursement rate, and therefore, are not fully reimbursed. This has forced many physicians to stop treating patients who rely on IG, simply because they can’t afford to continue operating at a deficit. The result is that patients either go without treatment or resort to going to a hospital where treatment is mandated.

In addition, “Medicare rates primarily cover the cost of the drug itself,” says Kris McFalls, patient advocate for IG Living magazine, written for patients who depend upon IG products and for their healthcare providers. “For IVIG, reimbursement rates allow minimal to no reimbursement for the cost of acquisition, distribution, supplies or nursing. Subcutaneous IG (SCIG), which is covered under the durable medical equipment benefit, does cover part of the cost of the pump, but SCIG reimbursement is available only to PIDD patients.”

What’s more, reimbursement formulas for IG products often squeeze out physician and patient choice. Not all products are priced the same. So, to keep costs down and maximize profit margins, infusion providers may treat patients with only one or two of the less expensive IG products. In short, their decision is based upon profitability versus need. “IG products do not come in a generic form, and although some patients have no ill effects from changing products, many patients do,” explains McFalls. “Switching patients from one product to another can cause serious, long-lasting side effects, as each product uses different methods and ingredients to purify and stabilize IG products.” Jordan Orange, MD, PhD, FAAAAI, chair of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology’s Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committee clarifies this by saying, “A specific IVIG product needs to be matched to patient characteristics. A change in IVIG product should occur only with the active participation of the prescribing physician.”

The Role of the Healthcare Provider

What does this mean for healthcare providers in the current long market — a condition that started prior to the end of 2008? As of this writing, prices have temporarily stabilized and reimbursement rates have caught up with the cost of IG, which means most reimbursement rates will cover or exceed the cost of IG products. In this phase of the cycle, physicians can now return to treating IG patients as needed. Nonetheless, a short market is sure to return, encumbered by the same reimbursement issues that continue the fluctuating cycle.

To bring about stability, it is crucial for physicians to support an overhaul of the reimbursement model. Reform efforts are underway. At the federal level, the IVIG Access Act of 2009 was introduced in April. Among other things, the legislation grants the Secretary of Health and Human Services authority to update the payments for IVIG based on new or existing data, allows coverage for related items and services, and requires MedPAC to review IVIG payment and provide recommendations within a two-year period for any additional payment changes.

For the thousands of patients who rely on it, IG is a miraculous product. What IG does for patients is incredible, and there are still patients yet to be diagnosed, treated and brought back to health. Surely problems surrounding supply and reimbursement need to be resolved for their sake. The answer lies in stabilizing the market: having enough product so that the probability of success is high, but not so much product that physicians can’t afford to nurture patient demand. The key is affordable demand, which is highly dependent on revising the current ASP reimbursement model.