OPPS 2015 Final Rule: Impact from a Pharmaceutical Perspective

- By Bonnie Kirschenbaum, MS, FASHP, FCSHP

Reimbursement and revenue models in healthcare are changing with a move toward diversification in provision of service with payment for value and away from traditional fee-for-service. On Oct. 31, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued the calendar year 2015 Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment System Policy Changes and Payment Rates final rule [CMS- 1613-FC]. OPPS covers all outpatient services offered by a facility, so it pertains to every patient who passes through a facility who is not considered an inpatient. Understanding these rules is essential, since many commercial payers base their payment decisions on CMS rules, and all code sets and descriptions are universal to all payers.

In August 2000, CMS implemented the prospective payment system now known as OPPS, which subsequently progressed toward the increased use of bundled payments or packaging and away from fee-for-service that individually pays for each item or service. CMS is very clear in stating its philosophy on “packaging,” also known as bundling. According to CMS, “payment for multiple interrelated items and services into a single payment creates incentives for hospitals to:

• furnish services most efficiently and to manage their resources with maximum flexibility.

• maximize hospitals’ incentives to provide care in the most efficient manner.

• use the most cost-efficient item that meets the patient’s needs, rather than to routinely use a more expensive item, which often results if separate payment is provided for the items.

• effectively negotiate with manufacturers and suppliers to reduce the purchase price of items and services or to explore alternative group purchasing arrangements, thereby encouraging the most economical healthcare delivery.

• establish protocols that ensure that necessary services are furnished, while scrutinizing the services ordered by practitioners to maximize the efficient use of hospital resources.”

CMS uses averaging to establish a payment rate that may be more or less than the estimated cost of providing a specific service or bundle of specific services for a particular patient. This occurs when data from higher-cost cases requiring many ancillary items and services is merged with data from lower-cost cases requiring fewer ancillary items and services. The packaging essentially includes all items and services that are typically integral, ancillary, supportive, dependent or adjunctive to a primary service.

Drug Reimbursement in 2015

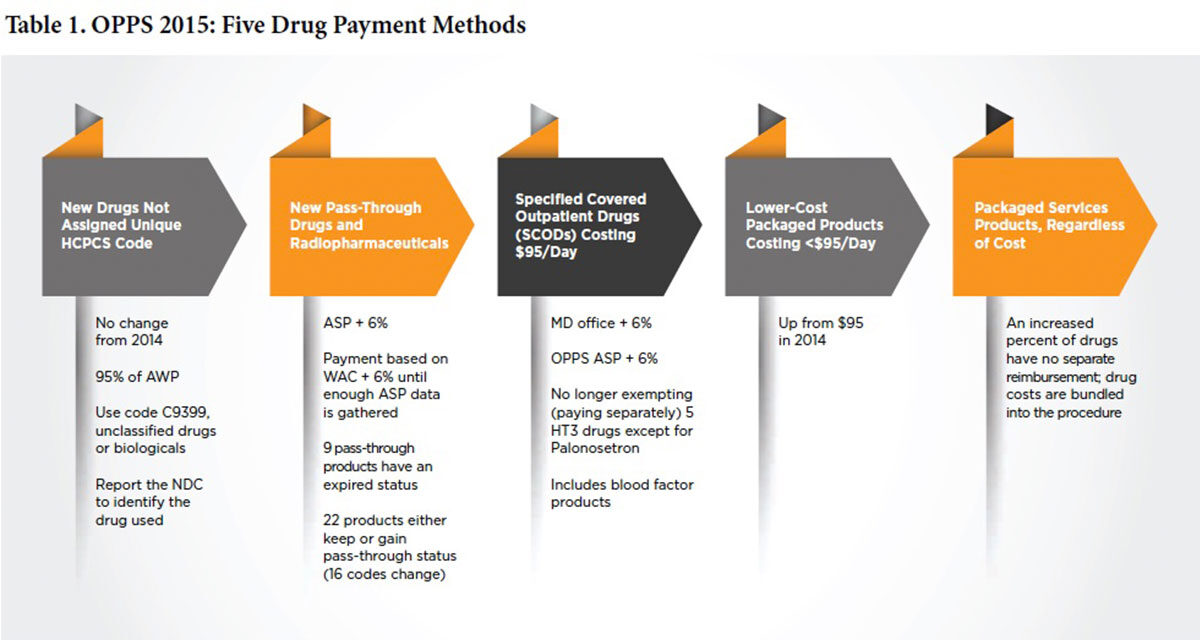

As shown in Table 1, drugs, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals will continue to be reimbursed in one of several ways as pass-through drugs, separately payable drugs and non-separately payable products that are bundled, or packaged, into reimbursement for the service or procedure. Bundling, or packaging, means there is no separate identified payment for the product. Because the category of pass-through drugs is designed for new products, the list is not static; each year, a number of products flow onto it and some off of it often with code (16 in 2015) and status indicator (SI) changes. A list of these pass-through drugs can be viewed at www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/11/10/2014-26146/medicare-and-medicaidprograms-hospital-outpatient-prospective-payment-and-ambulatory-surgical.

Specific Covered Outpatient Drugs (SCODs)

Specific products costing more than $95 per day (up from $90 in 2014) with defined Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, some of which may be brand-specific, fall under SCODs. Reimbursement is based on converting the actual dose of the drug given into CMS-defined billing units that are reimbursed at average sales price (ASP) plus 6 percent (sequestration] then deducts approximately 2 percent). ASP methodology is based on a number of factors, including the sale price of the drug by the manufacturer to the distributor (not the purchase price); but, again in 2015, calculations do not include 340B sales price. Since billing unit calculation errors remain the biggest CMS-identified error, doses must be carefully converted into billing units. Under-reporting billing units results in both lower reimbursement, as well as misrepresentation of what it actually costs to treat a patient with these products. This is extremely important because this claims data is subsequently used to determine future rates.

What’s Bundled and What’s Not?

There are two different types of bundles for drugs, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals. The first and easiest to understand is the nonseparately payable category based on drug cost as defined by CMS (and not by what is actually paid or charged). This year, the cut-off has risen to $95 per day. The second is defined by services or procedures that include certain drugs regardless of cost. Correctly dispersing funds internally from this ever-growing category has huge implications.

Comprehensive Ambulatory Payment Classifications (C-APCs)

Consistent with the trend in past years, CMS is packaging more services into composite APCs. Effective Jan. 1, hospitals won’t receive separate payment for argatroban, bivalirudin, clevidipine or topical thrombin “when administered to a patient receiving a comprehensive service,” regardless of pharmaceutical cost. Items and services packaged or included in payment for a primary service in the 2014 OPPS rule included five new categories of supporting items and services:

- Drugs, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals that function as supplies when used in a diagnostic test or procedure

- Drugs and biologicals that function as supplies when used in a surgical procedure, including skin substitutes (skin substitutes were classified as either high or low cost and are packaged into associated surgical procedures with other skin substitutes of the same class)

- Certain clinical diagnostic laboratory tests

- Certain procedures described by add-on codes

- Device removal procedures

In certain cases, a separate payment will be made if the item or service is furnished on a different date of service as the primary service.

Under the new C-APC payment policy, a single payment for each of 25 C-APCs covers all related or adjunctive hospital items and services provided to a patient receiving certain primary procedures that are either largely device-dependent or represent single-session services with multiple components. Items packaged for payment provided in conjunction with the primary service also include all drugs, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals, regardless of cost, except those drugs with pass-through payment status and those that are usually self-administered, unless they function as packaged supplies.

CMS also will conditionally package all ancillary services assigned to APCs with a geometric mean cost of $100 or less prior to packaging as a criterion to establish an initial set of conditionally packaged ancillary service APCs. When these ancillary services are furnished by themselves, CMS will make separate payment for these services. Exceptions to the ancillary services packaging policy include preventive services, psychiatry-related services and drug administration services.

The drug administration exclusion is important because even if the drug itself is not being paid for separately, its preparation and administration are being paid for separately through drug administration fee codes. Therefore, it’s essential that these are correctly applied with the required documentation in place, and that they are traceable through the revenue cycle without problematic hard stop edits. The electronic medication administration record or electronic health record can be used to create accurate documentation, as well as a decision tree concerning which codes apply to which products. Remember, the administered drug must be billed for (even if it won’t be paid separately or it’s a zero-priced drug) in order for drug administration fees to be paid.

Collecting Data from Off-Campus Provider-Based Departments

The groundwork was laid for this new rule in 2014, when CMS requested public comments regarding the best method for collecting data that would allow it to analyze the frequency, type and payment for physicians’ and outpatient hospital services furnished in off-campus provider-based hospital outpatient departments. This was precipitated by the increasing trend of hospitals purchasing specialty physician practices and then raising the prices for care, which caught the eye of federal regulators. That led CMS to establish a rule requiring the volume of outpatient care occurring in hospital-owned settings to be recorded.

CMS’s analysis of vast volumes of claims data has shown a divide between Medicare payments for hospital outpatient services (generally higher) and those for the same services furnished in a freestanding clinic or physician’s office (generally lower). As such, CMS intends to develop a better understanding of which practice expenses are typically incurred by the hospital, physicians and practitioners in a setting, and whether the facility and nonfacility site of service differentials adequately account for these costs.

Gathering information on the shift from physician practice site to hospital ownership is the first step. Data collection begins by requiring hospitals to report a modifier using a new place-of-service code on professional claims for services provided in an off-campus, provider-based hospital department. This data collection will be voluntary in 2015 and required in 2016.

Payers, including CMS’s Medicare program, are experimenting with a variety of payment initiatives that partner with providers to control costs while improving quality and member satisfaction. The models have a variety of names — bundled payments, consolidated payments, payments for episode of care, a bundle of once-a-month, incremental payment, new patient payment or patient month payment — all designed to replace traditional fee-for-service payments, including drugs on a line-item basis. CMS describes its program as “packaged services in composite APCs.” Regardless of which name is used, the basic principle remains the same: a fixed inclusive payment for a defined treatment, procedure or condition that is based on cumulated historical payments gleaned from claims data, as well as best practice from other sources.

If these payment initiatives are based on accurate data, well-designed and effectively implemented, they should be able to reward providers with strong financial incentives. Hospitals would be incentivized to work collaboratively with providers, and silos within the institution would be broken down from traditional roles and interests.

Healthcare providers should foster a discussion with their finance and revenue cycle teams about the need for transparent, realistic and defensible pricing of at least the pharmacy and drug administration components of the charge description master. If participating in the 340B program, providers should ensure that all requirements are being met and that there is a clear understanding of the eligible patient definition that is supported by their IT infrastructure. An accurate procedure-specific tally is essential because payments will be based on cumulated claims data from years past and may be adjusted for several factors. Billing accuracy, revenue cycle team skill and IT infrastructure robustness will all come into play as these rates are determined.

Editor’s Note: The content of this column is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.