The Role of Vaccines in Global Disease Prevention

New breakthroughs are giving developing countries the best shot at disease-free living and longevity, but challenges of financing, delivery strategies, efficacy and safety remain.

- By Trudie Mitschang

The year is 2020, and the state of the global health landscape is vastly different from the one we see today. Polio and measles have been virtually eradicated worldwide, as have neonatal and maternal tetanus cases. The widespread use of vaccines against pneumococcal, rotavirus, meningococcal and HPV disease have inspired new and more ambitious international health and immunization guidelines, revolutionizing the state of the vaccine marketplace. Perhaps most significantly, breakthrough vaccines have been introduced to combat even the most lethal diseases, including malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. Sound like a utopian pipe dream? Perhaps not.

Aggressive growth within the vaccine industry in recent years has resulted in significant achievements, especially when it comes to increasing immunization access in developing countries. Industry analysts predict that by 2020, manufacturers in developing countries may have acquired the capacity to make their own state-of-the-art vaccines tailored to meet their specific needs. Such a contribution to the global vaccine supply could put many of those countries on more equal footing with their industrialized counterparts when it comes to infectious disease control and prevention.

A Surge in Vaccine Development

The first decade of this century has been touted as the most productive in the history of vaccine development. New lifesaving vaccines have been introduced for meningococcal meningitis, rotavirus diarrheal disease, avian influenza caused by the H5N1 virus, pneumococcal disease and cervical cancer caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the next 10 years will spur an increased demand for some of these newer vaccines, especially in developing countries. New vaccine delivery systems are also anticipated, as devices that use needles may largely be replaced with innovative approaches such as aerosol formulations sprayed in the nose (already available in an influenza vaccine) or lungs.1

Since the year 2000, the vaccine market has almost tripled, exceeding $17 billion in global revenue by mid- 2008, and making the vaccine industry one of the fastest growing sectors of industry.1 Most of this expansion has come from sales in industrialized countries of newer, costlier vaccines, which account for more than half of the total value of vaccine sales worldwide. There are also a large number of candidate vaccines in the late stages of research and development — more than 80, according to recent unpublished data. Furthermore, about 30 of these candidates aim to protect against diseases for which no vaccines are currently available.2

According to a report by WHO, the surge in new vaccine development can be largely attributed to three key factors: the use of innovative manufacturing technology; growing support from public-private product development partnerships; and new funding resources and mechanisms. At the same time, the industry has seen significant growth in the capacity of manufacturers in developing countries to contribute to the supply of traditional childhood vaccines. Since 2000, the demand for these vaccines has grown steadily in an effort to meet the needs sparked by several major initiatives to combat polio, measles and neonatal and maternal tetanus. Currently, there are seven vaccines recommended for distribution and use in developing countries:

- DTP, for diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis

- BCG, for tuberculosis

- measles

- polio

- yellow fever

- hepatitis B

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

Expanding immunization coverage for basic vaccines is a proven, cost-effective method for saving lives in the developing world. Globally, increased access to vaccinations has saved more than 20 million children and is widely considered one of the most significant successes in public health. For example, the death rate due to childhood measles has declined 75 percent since the year 2000, while measles immunization rates have increased to 82 percent worldwide since 1990.3 Polio vaccine rates have also seen dramatic increases, thanks in part to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI); incidence of the disease went from 350,000 cases in 1988 to 1,652 cases in 2008.4

Envisioning a World Without Polio

In 1988, polio was endemic in 125 countries, resulting in close to 1,000 incidents of paralysis per day.4 That same year, the World Health Assembly (WHA) passed a resolution calling for global eradication of the disease. The GPEI, an international partnership, was initiated to achieve that goal by 2018, and to date, polio eradication efforts have resulted in several landmark successes. For instance, India, long regarded as the nation facing the greatest challenges to eradication, was removed from the list of polio-endemic countries in February 2012. And, outbreaks in previously polio-free countries were nearly all stopped. Currently, a plan is in place to boost vaccination coverage in Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan, the three remaining polio endemic countries, to levels needed to stop polio transmission. Despite the successes, outbreaks in recent years in China and West Africa due to importations from Pakistan and Nigeria, respectively, highlight the continued threat of resurgence. By some estimates, failure to eradicate polio could lead within a decade to as many as 200,000 paralyzed children a year worldwide.5 “Polio eradication is at a tipping point between success and failure,” said Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of WHO. “We are in emergency mode to tip it toward success — working faster and better, focusing on the areas where children are most vulnerable.”6

Once achieved, polio eradication would generate net benefits of $40 billion to $50 billion globally by 2035, with the bulk of savings in the poorest countries, calculated based on investments made since the GPEI was formed and savings from reduced treatment costs and gains in productivity. “We know polio can be eradicated, and our success in India proves it,” said Kalyan Banerjee, president of Rotary International, a global humanitarian service organization. “It is now a question of political and societal will. Do we choose to deliver a polio-free world to future generations, or do we choose to allow 55 cases this year to turn into 200,000 children paralyzed for life, every single year?”6

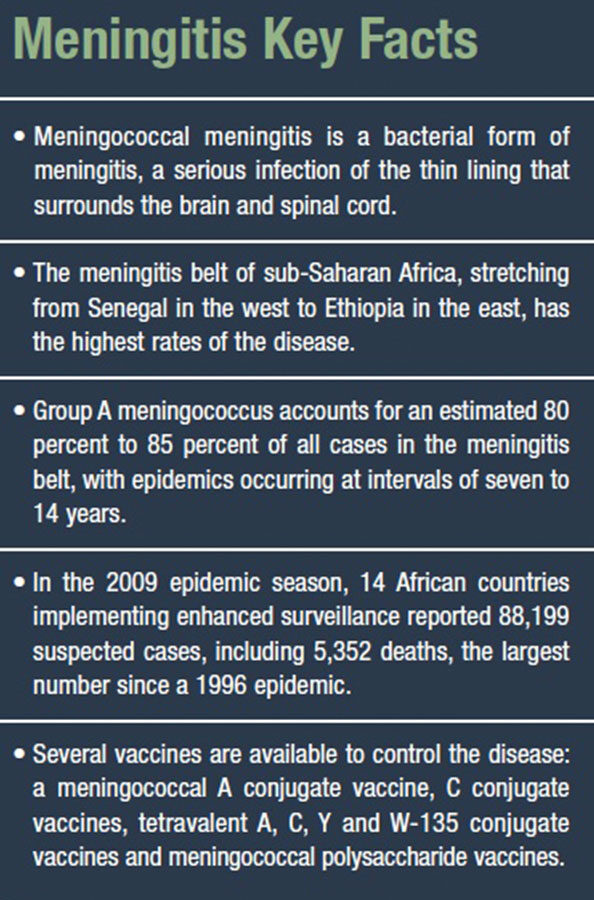

Immunizing the “Meningitis Belt”

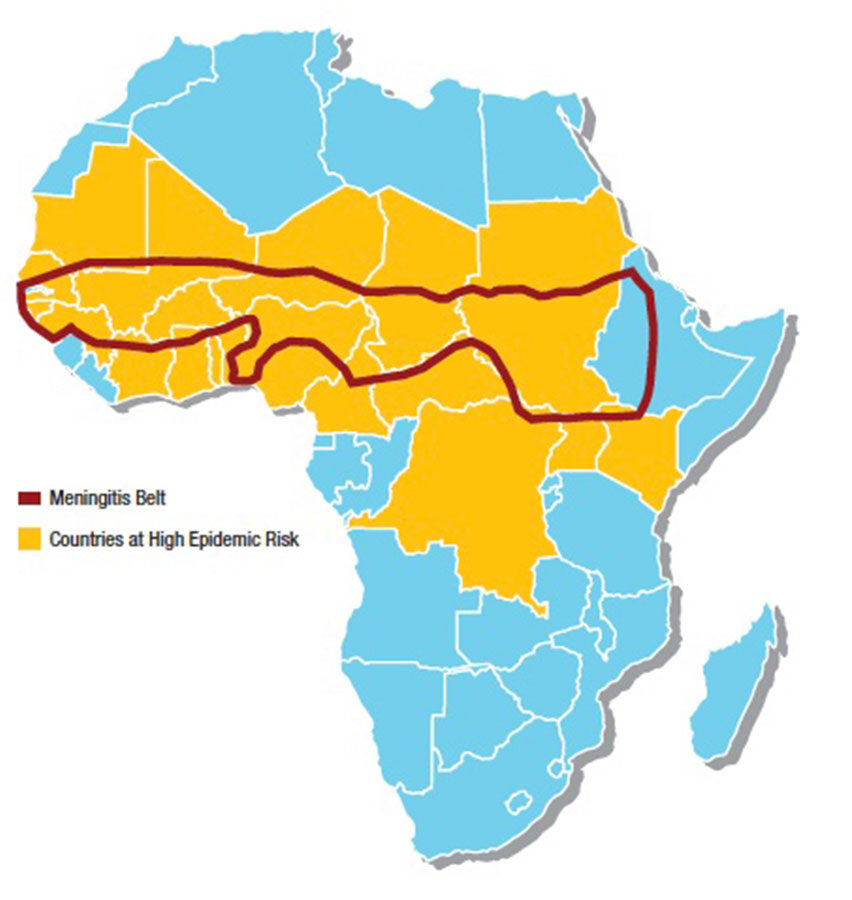

Meningococcal meningitis occurs in small clusters throughout the world and accounts for a variable proportion of epidemic bacterial meningitis. The largest burden of meningococcal disease occurs in an area of sub-Saharan Africa comprising 26 countries and known as the “meningitis belt,” which stretches from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east.7

In 2001, PATH, an international nonprofit organization, and WHO partnered to create the Meningitis Vaccine Project to develop, test, produce and provide vaccines that prevent meningococcal disease in the meningitis belt. In 2010, the project launched a new vaccine called MenAfriVac using an innovative vaccine-development model involving partners with expertise in technology, materials and manufacturing located on four continents. The vaccine was produced at one-tenth the cost of a typical new vaccine, costing less than 50 cents a dose. It also signified the first time a vaccine was designed specifically for Africa and became the first vaccine ever introduced in Africa prior to reaching any other continent.7

According to published materials, MenAfriVac has several advantages over existing polysaccharide vaccines: It induces a higher and more sustainable immune response against group A meningococcus; it reduces the carriage of the bacteria in the throat and, thus, its transmission; it is expected to confer long-term protection not only for those who receive the vaccine, but on family members and others who would otherwise have been exposed to meningitis; it is available at a lower price than other meningococcal vaccines; and it is expected to be particularly effective in protecting children under 2 years of age, who do not respond to conventional polysaccharide vaccines.

It is hoped that all 26 countries in the African meningitis belt will have introduced this vaccine by 2016. High coverage of the target age group of 1 year to 29 years has the potential to eliminate meningococcal A epidemics from this region of Africa.7

Fighting Measles and Rubella in Rwanda

Launched in March of this year, Rwanda’s measles-rubella (MR) vaccination campaign is the beginning of an effort to vaccinate more than 700 million children under 15 years of age against these two disabling and deadly diseases. The combined MR vaccine will be introduced in 49 countries by 2020 thanks to financial support from the GAVI Alliance, a public-private partnership committed to saving children’s lives and protecting people’s health by increasing access to immunization in developing countries.8 The support builds on the efforts of the Measles & Rubella Initiative (M&RI) that have helped countries to protect 1.1 billion children against measles since 2001. The initiative is a partnership of many health agencies, vaccine companies, donors and others, but it is led by the American Red Cross, the United Nations Foundation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF and WHO.

Because of this initiative, Rwanda became the first sub- Saharan African country to provide MR vaccine nationwide with GAVI support. The vaccine will stop not only the transmission of rubella from mother to child, preventing children being born with severe birth defects, but also protect children against measles, which is highly contagious. Every year, an estimated 112,000 children, mostly in Africa, South Asia and the Pacific Islands, are born with handicaps caused by their mothers’ rubella infections. “Rwanda has made great strides over the past four years in child survival by introducing vaccines against leading child killers, including pneumonia and diarrhea,” said Dr. Agnes Binagwaho, Rwanda’s Minister of Health. “The introduction of the combined measles-rubella vaccine is one more important step to ensuring that all children in Rwanda receive the full immunization package. In our efforts to eliminate measles, we have raised measles coverage through campaigns and routine immunization to higher than 95 percent.”8

Five other countries — Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ghana, Senegal and Vietnam — are expected to introduce the MR vaccine through vaccination campaigns with GAVI support by the end of 2013. “Investing in rubella will provide a much-needed boost to improving women’s and children’s health in poor countries. GAVI’s support for measles-rubella campaigns will help accelerate global progress in controlling two life-threatening diseases,” said Dr. Seth Berkley, GAVI Alliance CEO. “Rubella vaccine has been available since the 1970s in many parts of the world. Accelerating the introduction of rubella vaccine in developing countries will spread the benefits of the vaccine to those in most need and build on country efforts to control measles with a cost-effective combined vaccine. It brings us one step closer to ensuring that every child everywhere is fully immunized.”8

Promising Malaria Vaccine Faces Setbacks

There is currently no vaccine that offers complete protection against malaria, but hopes have been high regarding RTS,S, the most advanced candidate malaria vaccine developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Unfortunately, in March 2013, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed the effectiveness of the vaccine wanes over time, with the shot protecting only 16.8 percent of children over 4 years, according to trial data. The disappointing results raised further questions about whether RTS,S can make a difference in the fight against the disease, a major cause of illness and death among children in sub-Saharan Africa. Results from a separate trial last year showed the vaccine was only 30 percent effective in babies. The new data found that although RTS,S initially had a protection rate as high as 53 percent, after an average of eight months, that effectiveness faded swiftly.9 “It was a bit surprising to see the efficacy waned so significantly over time. In the fourth year, the vaccine did not show any protection,” said Ally Olotu of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kenya, who led the follow-up study. Malaria, caused by a parasite carried in the saliva of mosquitoes, is endemic in more than 100 countries worldwide. According to WHO, malaria infected around 219 million people in 2010, killing some 660,000 of them. Control measures such as insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor spraying and anti-malaria drugs have helped cut malaria cases and deaths significantly in recent years, but drug resistance is growing, and experts say an effective vaccine could be a vital tool in eradicating the disease. Phillip Bejon, another researcher at KEMRI, asserts there is still a clear benefit to the GSK vaccine. “Many of the children (in Africa) will experience multiple episodes of clinical malaria infection, but overall we found that 65 cases of malaria were averted over the four-year period for every 100 children vaccinated,” he said. “We now need to look at whether offering a vaccine booster can sustain efficacy for longer.”10

Addressing the Cold Chain Challenge

HIV, malaria and tuberculosis have long represented major global health challenges. Although promising research is underway to develop vaccines for these diseases, considerable hurdles remain for countries where transporting and storing live vaccines in a continuously cold environment (around 2 degrees Celsius to 8 degrees Celsius or below) is simply not possible. If a cold chain cannot be maintained for a live vaccine, there is a high risk it could become unsafe and lose effectiveness.

A recent published study by scientists at King’s College London may offer promise in overcoming this hurdle. Results of the study demonstrated the ability to deliver a dried live vaccine to the skin without a traditional needle, and showed for the first time that this technique is powerful enough to enable specialized immune cells in the skin to kick-start the immunizing properties of the vaccine.11 “We have shown that it is possible to maintain the effectiveness of a live vaccine by drying it in sugar and applying it to the skin using microneedles — a potentially painless alternative to hypodermic needles,” said Dr. Linda Klavinskis from the Peter Gorer Department of Immunobiology at King’s College London. “We have also uncovered the role of specific cells in the skin which act as a surveillance system, picking up the vaccine by this delivery system and kick-starting the body’s immune processes.”11

The report went on to state that the discovery opens up the possibility of delivering live vaccines in a global context, without the need for refrigeration. It could potentially reduce the cost of manufacturing and transportation, improve safety and avoid the need for hypodermic needle injection, reducing the risk of transmitting bloodborne disease from contaminated needles and syringes. “This new technique represents a huge leap forward in overcoming the challenges of delivering a vaccination program for diseases such as HIV and malaria. But these findings may also have wider implications for other infectious disease vaccination programs, for example infant vaccinations, or even other inflammatory and autoimmune conditions such as diabetes,” said Klavinskis.11

A Commitment to the Future

In recent years, efforts to develop and deliver vaccines to the world’s poorest countries have been on the upswing. In January 2010 at the World Economic Forum, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation launched the Decade of Vaccines by pledging $10 billion over 10 years to support worldwide vaccination efforts. The foundation also challenged other global partners to demonstrate their continuing commitment, with a singular goal in mind: to dramatically reduce child mortality by the end of the decade. The effort is an ambitious one, and stakeholders agree there is no easy formula for success. Achieving this goal will require a multi-pronged approach, including the strengthening of current health systems and immunization programs; new public-private partnerships for vaccine development; new long-term global financing mechanisms; innovative and sustainable delivery strategies; and improved advocacy and communication.

The good news is that today, as never before, governments have an unprecedented number of partners willing to help pay for vaccines and immunization. In a media release following the announcement of the Decade of Vaccines pledge, Dr. Christopher Elias, president and CEO of PATH, said: “The commitment announced by Bill and Melinda Gates will have a tremendous impact on children and families in the poorest areas of the world. PATH is committed, as is the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to letting no child die from a preventable disease, and we are heartened by their continued efforts to move us one step closer toward a world where health is within reach for everyone.”

References

- World Health Organization, Unicef and The World Bank. State of the World’s Vaccines and Immunization, Third Edition. Accessed at www.unicef.org/immunization/files/SOWVI_full_report_english_LR1.pdf.

- World Health Organization, Unicef and The World Bank. State of the World’s Vaccines and Immunization: Unprecedented Progress. Accessed at www.who.int/immunization/fact_sheet_progress.pdf.

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Progress Towards Immunization: Winning the Fight Against Deadly Diseases. Accessed at www.gatesfoundation.org/livingproofproject/Documents/progress-towards-immunization.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hunting Down the Polio Virus, Jun. 5, 2009. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/news/2009/06/stop_polio.

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Accessed at www.polioeradication.org.

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative. What Are People Saying about Polio Eradication? Accessed at www.polioeradication.org/Aboutus/Peoplearesaying.aspx.

- PATH. The Promise of a New Vaccine: Conjugate Vaccine Will Stop Meningitis Epidemics Before They Start. Accessed at www.path.org/menafrivac/promise.php.

- United Nations Foundation. Over 700 Million Children in 49 Countries to Be Protected Against Measles and Rubella, Mar. 12, 2013. Accessed at www.unfoundation.org/news-andmedia/press-releases/2013/over-700-million-children-to-be-protected.html.

- Vogel, G. More Sobering Results for Malaria Vaccine. Science Now, Mar. 20, 2013. Accessed at news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2013/03/sobering-results-for-malaria-vac.html.

- Kelland, K, and Emery, G. Protection Offered by GSK Malaria Vaccine Fades Over Time. Reuters, Mar. 20, 2013. Accessed at www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/20/us-malariavaccine-gsk-idUSBRE92J1B620130320.

- The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Global Immunization: Diseases and Vaccines — A World View. Accessed at www.chop.edu/service/parents-possessing-accessingcommunicating-knowledge-about-vaccines/global-immunization/diseases-and-vaccines-aworld-view.html.