The Shift to Payment for Value Continues: OPPS 2016 Final Rule

- By Bonnie Kirschenbaum, MS, FASHP, FCSHP

THE SHIFT TO ICD-10 that began Oct. 1 and the continuing shift in reimbursement models toward payment for value versus traditional fee-for-service have resulted in significant payment changes. Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued the final 2016 hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS) and ambulatory payment classification (APC) system policy changes and payment rates rule with comment period [CMS-1613-FC] on Oct. 30, 2015.

The OPPS covers all outpatient services offered by a facility. Under the OPPS, averaging is used to establish a payment rate that may be more or less than the estimated cost of providing a specific service or bundle of specific services for a particular patient. This occurs when data from higher-cost cases requiring many ancillary items and services is merged with data from lower-cost cases requiring fewer ancillary items and services. The packaged pricing includes all items and services that are typically integral, ancillary, supportive, dependent or adjunctive to a primary service. What is key to understand is that new rates are based on claims data whether for bundles or fee-for-service. Submitting missing or inaccurate data will result in an artificially low rate the next payment year.

Following are the changes under the final 2016 OPPS rule. Understanding these changes is essential since many commercial payers base their decisions on those made by CMS, and all code sets and descriptions are universal to all payers.

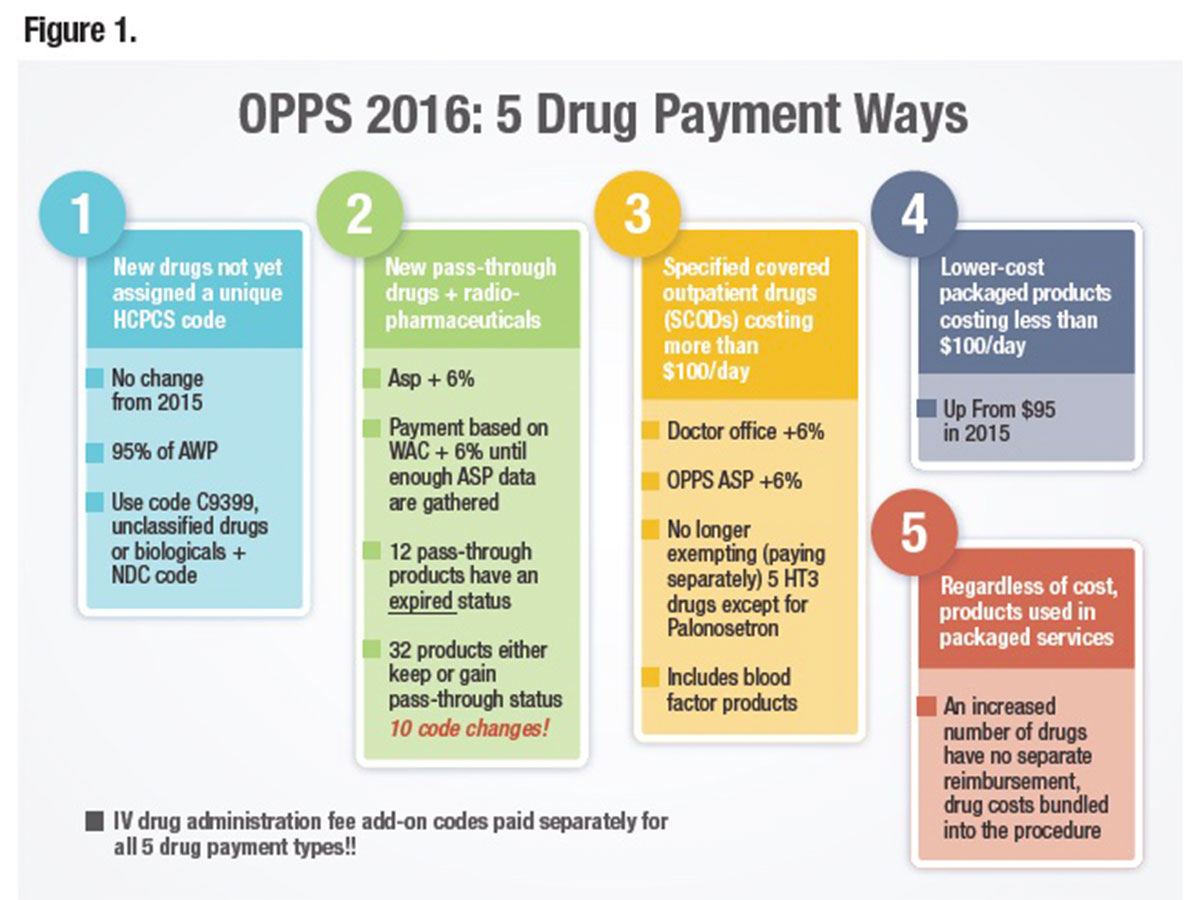

Drug Reimbursement in 2016

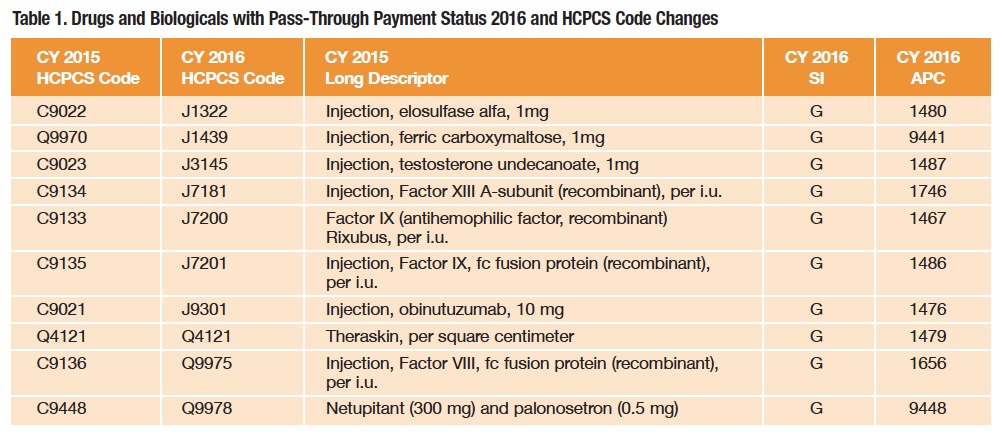

As shown in Figure 1, drugs, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals will continue to be reimbursed in one of several ways: as pass-through drugs, as separately payable drugs and as nonseparately payable products that are bundled or packaged into the reimbursement for the service or procedure. Bundling or packaging means there is no separate identified payment for the product, and disbursement of the bundled payment is left to the discretion of the facility. Because the category of pass-through drugs is designed for new products, the list is not static, and each year a number of products are added or removed with code (16 for 2016) and status indicator (SI) changes (Table 1).

Specific Covered Outpatient Drugs (SCODs)

Specific products costing more than $100 per day (up from $95 in 2015) with defined Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, some of which may be brand-specific, fall into the SCOD group. Reimbursement is based on converting the actual dose of the drug given into CMS-defined billing units that are reimbursed at the average sales price (ASP) plus 6 percent (sequestration then deducts approximately 2 percent). ASP methodology is based on a number of factors, including the sale price of the drug by the manufacturer to the distributor (not the purchase price). But, again in 2016, calculations do not include the 340B sales price. Since billing unit calculation errors remain the biggest CMS-identified error, providers should carefully examine the conversion of doses into billing units. If billing units are underreported, facilities will receive less money since it misrepresents what it actually costs to treat a patient. Providers need to remember that all claims data are subsequently used to determine future rates.

What’s Bundled and What’s Not

There are two different types of bundles under which drugs, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals fall. The first and easiest to understand is the non-separately payable category that is based on the drug cost as defined by CMS (not by what is actually paid or charged). In 2016, the cut-off rose to $100 per day. The second type is defined by services or procedures that include certain drugs regardless of cost. Correctly disbursing funds internally from this ever-growing category has important implications.

Restructuring of APCs. CMS annually reviews and revises the OPPS APC groups to consider changes in medical practices and technologies and the addition of new services and cost data or other relevant information. This year, CMS has restructured, reorganized and consolidated APCs to create nine clinical APC families that will include various surgical and diagnostic procedures.

Comprehensive APCs (C-APCs).C-APCs are APCs that provide for an encounter-level payment for a designated primary procedure, plus all adjunctive and secondary services provided in conjunction with the primary procedure. The current 25 C-APCs mostly include procedures for the implantation of costly medical devices. For 2016, CMS has added nine new C-APCs, including some surgical APCs and a new C-APC for comprehensive observation services. CMS also is collecting data through the use of an HCPCS modifier on all services related to a C-APC primary procedure that are reported on a separate claim. This data collection allows for the assessment of the costs of all adjunctive services related to C-APC services, even if reported on a separate claim.

To reiterate, the concept of packaging or bundling refers to all-inclusive Medicare payments for some of the most common tests and procedures instead of paying for the components separately. There are two major paths to the march toward a true OPPS: 1) packaged payments for C-APCs within “clinical families,” and 2) packaged payments for certain ancillary services that are integral, supportive, dependent or adjunctive to a primary service. As expected and consistent with the trend set in past years, CMS is proposing to package more services into composite APCs. What this means for pharmacies is that effective Jan. 1, hospitals won’t receive separate payment for abciximab, bivalirudin or mitomycin ophthalmic when administered to a patient receiving a comprehensive service, regardless of pharmaceutical cost.

Under the C-APC payment policy, a single payment for each of the C-APCs covers all related or adjunctive hospital items and services provided to a patient receiving certain primary procedures that are either largely device-dependent or represent single-session services with multiple components. Items packaged for payment provided in conjunction with the primary service also include all drugs, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals, regardless of cost, except those drugs with pass-through payment status and those drugs that are usually self-administered, unless they function as packaged supplies.

CMS also will conditionally package all ancillary services assigned to APCs with a geometric mean cost of $100 or less prior to packaging as a criterion to establish an initial set of conditionally packaged ancillary service APCs. When these ancillary services are furnished by themselves, CMS will make separate payment for these services. Exceptions to the ancillary services packaging policy include preventive services, psychiatry-related services and drug administration services.

The continuing drug administration exclusion is important because even if the drug itself is not being paid for separately, its preparation and administration are being paid for separately through the drug administration fee codes. It’s essential that these are correctly applied with the required documentation in place and that it is traceable through the revenue cycle without problematic hard stop edits. It might help if providers use an electronic medical administration record or electronic health record to create accurate documentation, as well as a decision tree that shows which codes apply to which products.

Providers need to remember that they must bill for the drug administered (even if it won’t be paid separately) for drug administration fees to be paid. This applies to white-bagged drugs, zero-priced drugs (such as patient assistance supplied drugs) and all drugs where packages and bundles apply. Providers should also be aware of the 2016 APC renumbering that applies to each of the drug administration codes. They should also be aware that “chemo” includes traditional chemotherapy, immunotherapy, biologics and biosimilars (all considered complicated).

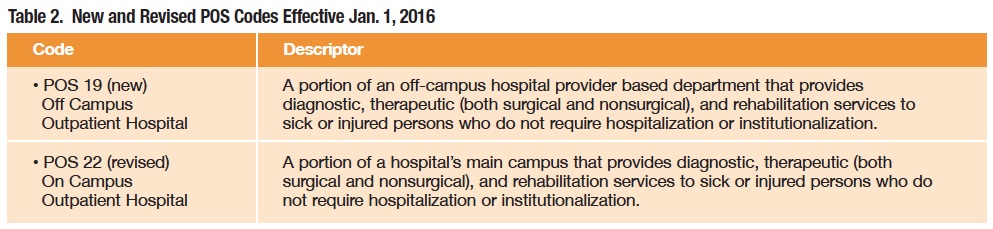

Changes to Place of Service (POS) Codes (MLN Matters number MM9231)

The POS code set provides care-setting information necessary to appropriately pay Medicare and Medicaid claims. To differentiate between on-campus and off-campus provider-based hospital departments, CMS has created codes for each effective Jan. 1 (Table 2). This code set was precipitated by the ever-increasing trend of hospitals purchasing specialty physician practices and then raising the prices for care to the extent that federal regulators opted not to turn a blind eye to the tactics.

A rare bipartisan budget agreement reached in late October included many automatic cuts. Due to reductions in Medicare payments for hospital-owned outpatient centers, payments would have to be at the lower outpatient fee schedules for physician offices and clinics. However, reductions would be only for new acquisitions; medical practices and clinics previously acquired or opened by hospitals would continue to be reimbursed at the higher rates, which was a compromise from the original proposal of capping all outpatient care delivered at hospital sites at the lower rates.

For pharmacists, this classification provides a clear pathway for data collection on pricing practices used in the two settings, especially when combined with 340B status. These codes are in response to CMS’ plan to gather information on provider-based services. Effective Jan. 1, hospitals must start using a new modifier when billing for services rendered in provider-based departments, and physicians will use one of the two new POS codes. The mandate is seen as a possible precursor to reductions in payments to provider-based departments, which are higher than payments to freestanding clinics for the same services. See tinyurl.com/nv39mur for more details.

Providers should discuss with finance and revenue cycle teams the need for transparent, realistic and defensible pricing of at least the pharmacy and drug administration components of the charge description master. If a facility participates in the 340B program, it needs to ensure that all requirements are being met and that there is a clear understanding of the eligible patient definition that is supported by the IT infrastructure.

NOTICE Impacts Observation Patients

The Notice of Observation Treatment and Implication for Care Eligibility (NOTICE) Act requires hospitals to provide Medicare beneficiaries with written notification and a related verbal explanation at discharge or within 36 hours, whichever is sooner, if they receive more than 24 hours of outpatient observation services. This applies to all Medicare patients when they receive observation care but aren’t actually admitted to the facility. Unfortunately, this rarely happens now, and most patients are shocked when they receive their medical bills.

The new requirements stipulate that the notification must explain in easy-to-understand language why the patient was admitted to observation and the potential financial implications. The implications are more than just the hospital charges, since older adults admitted for observation often must pick up the costs of additional care at a skilled nursing facility. Medicare only covers those costs if the inpatient stay is at least three consecutive days, not counting observation days.

The Act also affects the packaging of observation services, which requires a new observation C-APC and inclusion into the payment virtually all associated services such as the emergency room visit, labs and radiology, including infusions and injections. Payment for observation services is $2,111 with a new status indicator: J2.

For the pharmacist, this proposed rule has many implications, from re-examining drug distribution practices for observation patients to a revenue cycle standpoint and bundled payment fund distribution. Providers in facilities in the 340B program will need to pay attention to the implications of this proposed rule as well, much in the same way they do for surgical and diagnostic or treatment center locations serving both inpatients and outpatients. Managing utilization and controlling costs will be essential.

Bundled Payments for Knee and Hip Replacements

For knee and hip replacement surgeries, there is a unique five-year pilot program for bundled payments that encompasses 75 different areas of the country and more than 800 hospitals. The program requires hospitals to partly repay the government if patients contract avoidable infections and other complications; rewards with extra payments if patients do not; treats the surgeries as one complete service instead of a collection of individual services; and holds hospitals accountable for care up to 90 days after discharge. More details can be read about this program at goo.gl/ZurYux. Robust information technology and revenue cycle infrastructures are essential to provide the crucial analytics that will be necessary for this program.

Medicare Add-On Payments to Hospitals for New Technology

Medicare covers costly treatments for chronic conditions treated in the inpatient setting through add-on payments that are petitioned by the drug manufacturer. The latest approval was given to Blincyto (Amgen) when CMS decided that the drug was a significant improvement over existing treatments. The new rule, published in the Federal Register on Aug. 17, explains that Medicare will allow for a “new technology add-on payment” to hospitals for a portion of that amount, up to $27,000. The actual payment will depend on the duration of a patient’s hospital stay.

New Rules Designed to Control Costs, Improve Quality

Payers, including CMS’ Medicare program, are experimenting with a variety of payment initiatives that bring providers on board as partners to control costs while improving quality and member satisfaction. The models have a variety of names such as bundled payments, consolidated payments, payments for episode of care, a bundle of once-a-month, incremental payment, new patient payment or patient month payment. They’re all designed to replace traditional fee-for-service payments that pay for charges, including drugs, on a line-item basis. CMS describes their program as “packaged services in composite ambulatory patient classifications (APCs).” Regardless of the name being used, the basic principle remains the same: a fixed inclusive payment for a defined treatment or procedure or condition that is based on cumulated historical payments gleaned from claims data, as well as best practice from other sources.

If these initiatives are based on accurate data, are well-designed and effectively implemented, they should be able to reward effective providers with strong financial incentives. Hospitals would be incentivized to work collaboratively with providers, and silos within the institution would be broken down from traditional roles and interests to accomplish this.

Of course, an accurate procedure-specific tally is essential. Actual payment is based on cumulated claims data from years past and may be adjusted for several factors. The accuracy of billing, the skill of the revenue cycle team and the robustness of the IT infrastructure are all coming into play as these rates are determined.